The Classics

|

Why does it seem such a difficult business

to acquire a familiar knowledge of any foreign language,

and why is so much brain and so much time spent so

frequently on their acquisition with such scanty results?

The answer can be only one: because your teacher has

ignored the method of Nature, and given you a bad substitute

for it in his own devices; instead of speaking to you

and making you respond, in direct connection of the old

object with the new sound, and thus forming a living bond

between the thinking soul, the perceptive sense, and the

significant utterance, he sends you to a book, there to

cram yourself with dead rules and lifeless formulas about the

language, in the middle of which he ought to have planted

you at the start.

John Blackie,

Greek Primer: Colloquial and Constructive (London: Macmillan and Co., 1891)

|

Before relating my tales of woe and my tedious

|

|

A PLEA:

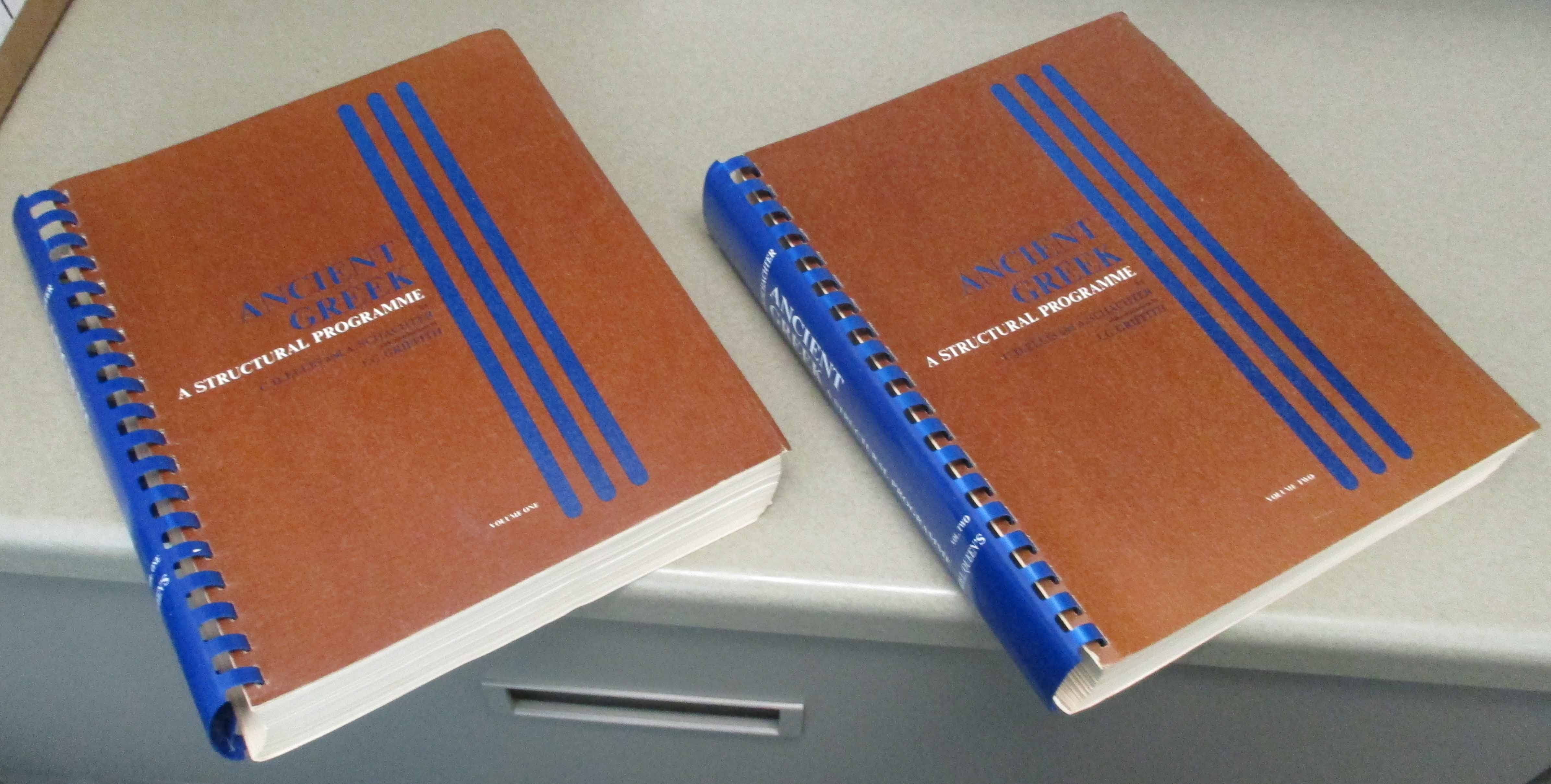

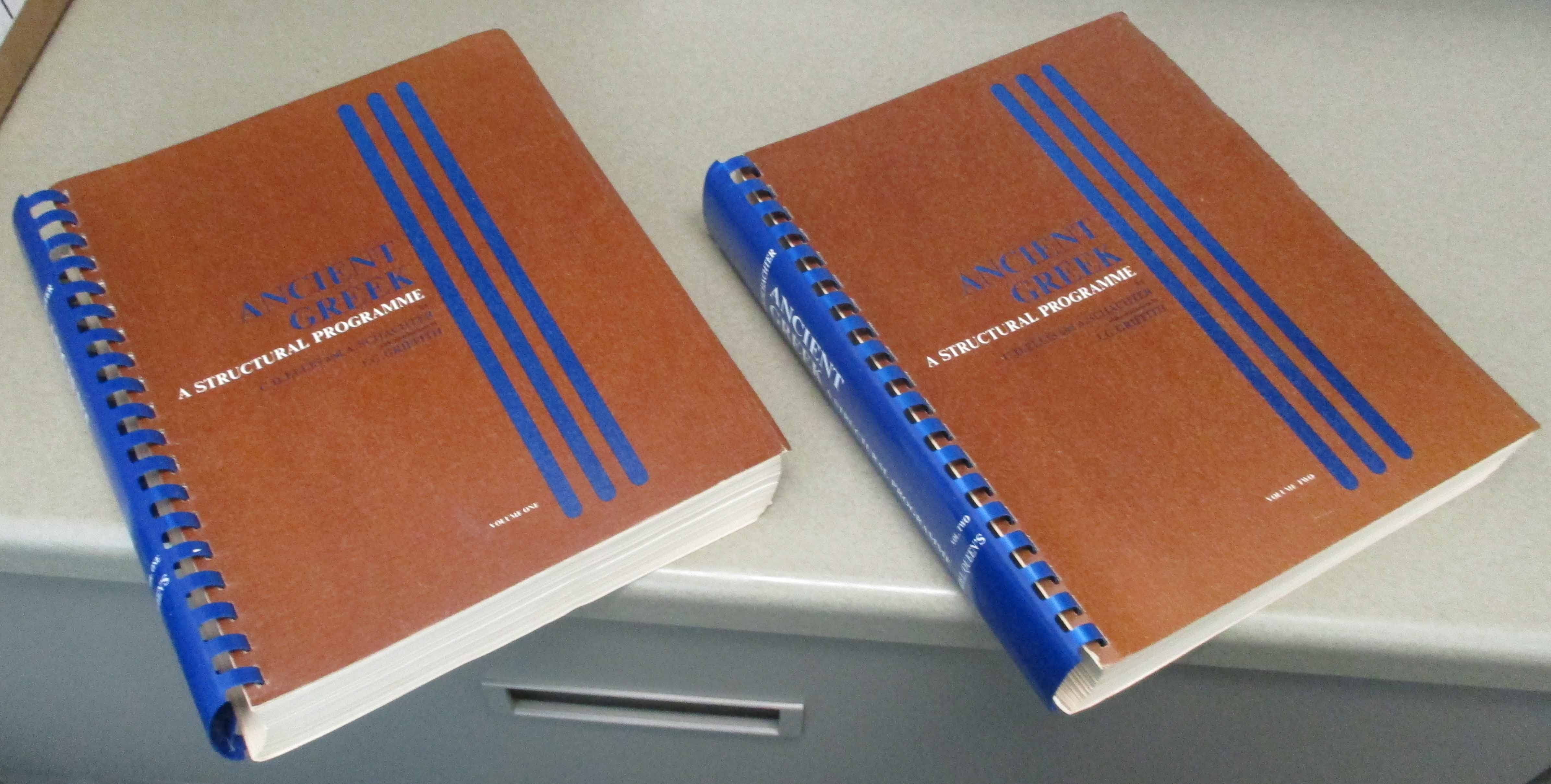

If anybody wishes to study Ellis/Schachter with me, remotely by Zoom or Teams or something similar,

just say the word and I would be thrilled beyond description.

We could even

|

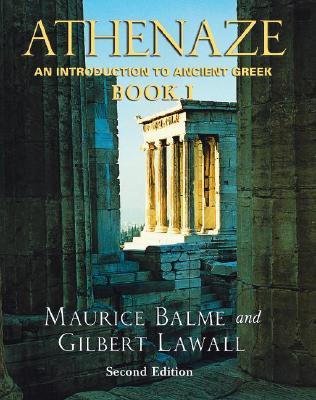

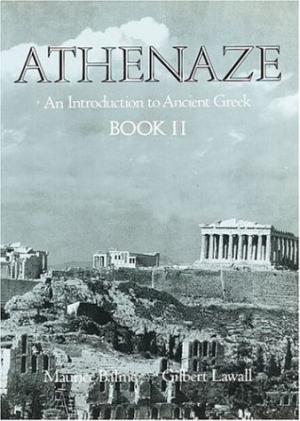

That’s all you need to know.

Now that we have located the above courses, everything that follows below the fold is hereby rendered naught more than meaningless babble.

No need to read it, unless you, too, wanted to kick your teachers.

Now for my autobiographical ravings, which are probably not too different from yours.

I shall hazard a guess that since you are interested in Caligula,

you are probably interested in Classical history, and you probably enrolled in Greek and/or Latin in high school or college.

Yes?

If so, I shall further hazard a guess that, after several years of studying Greek and/or Latin,

you emerged unable to speak, read, or write either language,

and could translate only with difficulty and constant reference to dictionaries and volumes of paradigm tables.

That is because we were all cheated. Deliberately. Intentionally.

Our teachers and professors never had any notion of teaching us either language, and they made sure we would give up.

Below is my personal story.

It will probably resonate all too painfully with you.

Yes, in this autobiographical story I do go off on tangents, and that’s

simply because I’ve been bottling this all up for four-fifths of my life.

Now I’m opening the bottle, and I’m discovering tons of rage I never even knew I had.

I admit, to my great embarrassment, that I have not learned either Latin or Greek, despite having “studied” them in school,

invariably under instructors and university professors who were unable to speak, read, or write the languages.

As I write this, I am merely at the opening few lessons of Greek, now that I have at long last found the well-designed courses listed in the box above.

So, I am not hammering this web page together to proclaim my knowledge, but my ignorance.

This web page is largely for my personal reference, so that I won’t forget where I recently found some nice resources.

Why do I post it publicly?

Because, unless I have failed, at least a few passages of this page should be entertaining,

and though I tell my stories from a vantage point of inexperience, a little bit of what I write should prove helpful.

Besides, there are fun stories below.

At least I think so.

The few Classics I have read (frightfully few) were all in translation.

I refused to read more, because I resented having to rely on translations.

I wanted to read the originals.

Maddeningly, I should have been able to read the originals.

You see, some of the relatives who raised me were Greek, but refused to speak (Modern) Greek with me.

Yes, they spoke Greek — quite a lot, really — but only with each other.

When I would enter the room, they would switch to English.

The ideology, at least in part, was simple: “We are Americans now! We speak only English!”

(I don’t think they ever used that exact phrase, but that was certainly the sentiment, expressed in various explicit ways.)

More to the point: The children must be raised as Americans.

Goodness gracious!

Truth be told, though, it was not my family that brought about my interest.

Had it been only nasty Greek relatives who spoke a tongue I could not understand, I would not have thought it worth understanding.

The person who lit my fire, in September 1971, when I was eleven, was my sixth-grade teacher at Zuñi Elementary School,

Manny Smith, formerly of Oswego (and Elmira?), NY, of all places, who moonlighted as an Equity actor.

It was funny to turn on the TV set and see my teacher in a public-service announcement and in

The Man and the City and so forth.

The public-service announcement, which I saw only once:

He portrayed a sleazy salesman, dressed, I think, in white dungarees, offering a used TV set at a bargain price.

His final sentence of the spiel: “And there’s no guarantee!” he said as he patted the top of the TV set with his hand,

only to see the screen explode.

He did a quick double take, and that was followed by a caption about caveat emptor.

In The Man and the City, he was the helium-balloon salesman at Uncle Cliff’s Family Land in the first episode,

speaking his single line to Anthony Quinn and a handicapped boy with a horribly exaggerated NY accent —

and I think he was dubbed. I watched the episode, and the next day we students were all amused to have seen him on the tube the night before.

He repeated his single line for us, as he had delivered it on camera, but that was not the line we had heard the night before.

It turns out that he was also in the pilot, The City, which I missed.

I’d so much love to get the entire series on video, but it has never been seen since its original airings in 1971.

Oh. Wait. Whoah. Here’s a clip from an episode.

This is from a 16mm print that somehow escaped from the vault.

Ah. I learn that this was from a TV movie from 1978, called Destiny of a Woman, which was stitched together from two episodes of The Man and the City.

To my genuine surprise, I still find this interesting. I thought I’d be cringing, but no, not at all.

Not great, by any means. It’s basically a soap, but not bad for a soap.

I wouldn’t put it in the same class as Napoléon vu par Abel Gance

or King of Jazz

or Valerie and Her Week of Wonders or

Una vez, un hombre... or

Rhymes for Young Ghouls or

Their First Mistake or

Search for the World’s Best Indian Taco, but it holds up.

Whether we loved Mr. Smith or hated him, we students found him fascinating.

One day a student asked him about his family origins.

He wasn’t expecting that and was rather taken aback.

After a double take, he began his story.

This was a story he had never practiced, and so he began quietly by telling us that his ancestors had emigrated to the US from Latvia.

Since nobody in class had heard of such a country, and since the name sounded funny, we all chuckled.

That was it. He stopped his story before he finished his first sentence.

We begged him to continue, but he refused.

It was surprising that such a tough guy, who specialized in comedy rôles and who loved making everybody laugh,

could be so insecure about such a minor little chuckle.

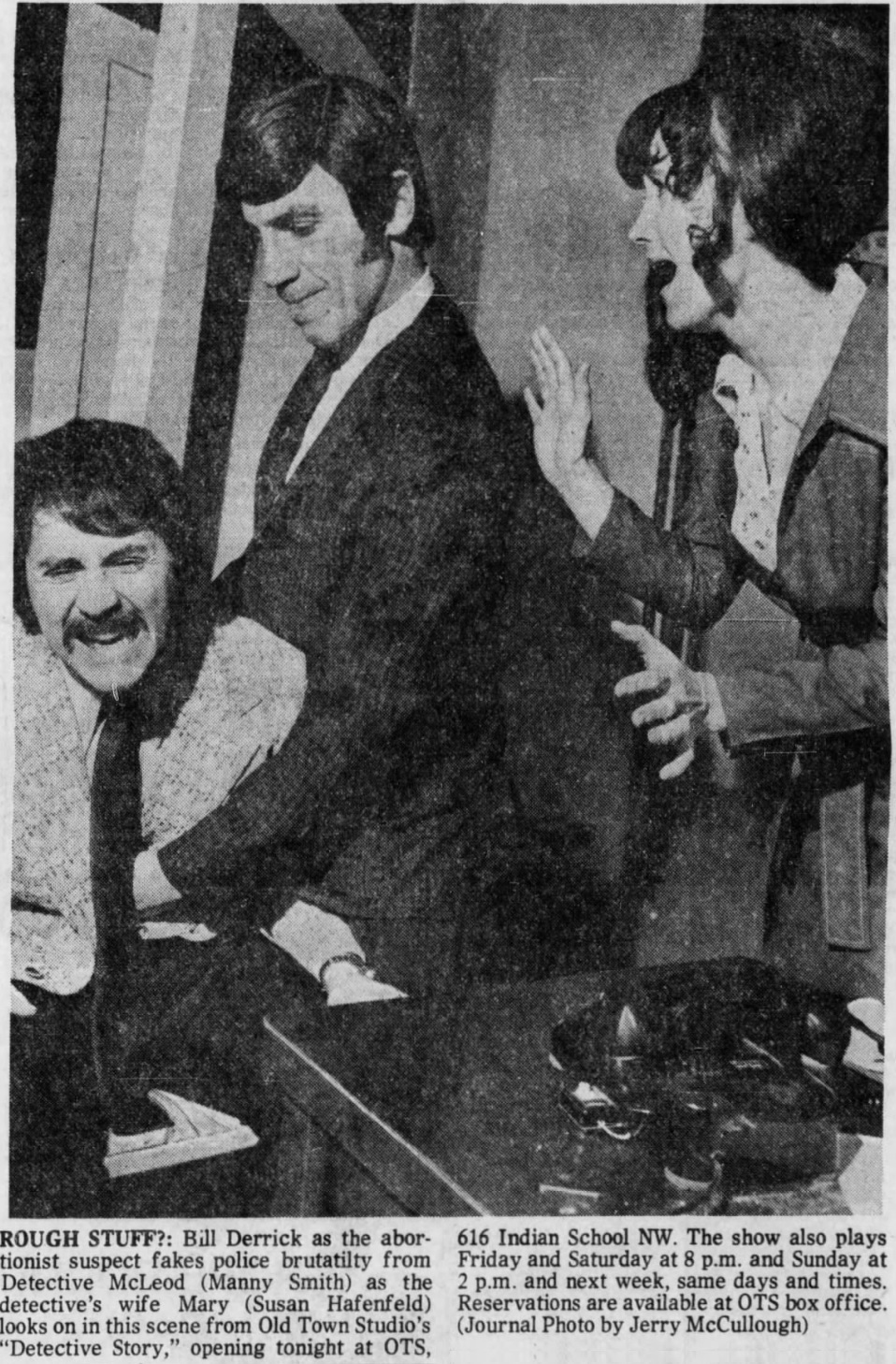

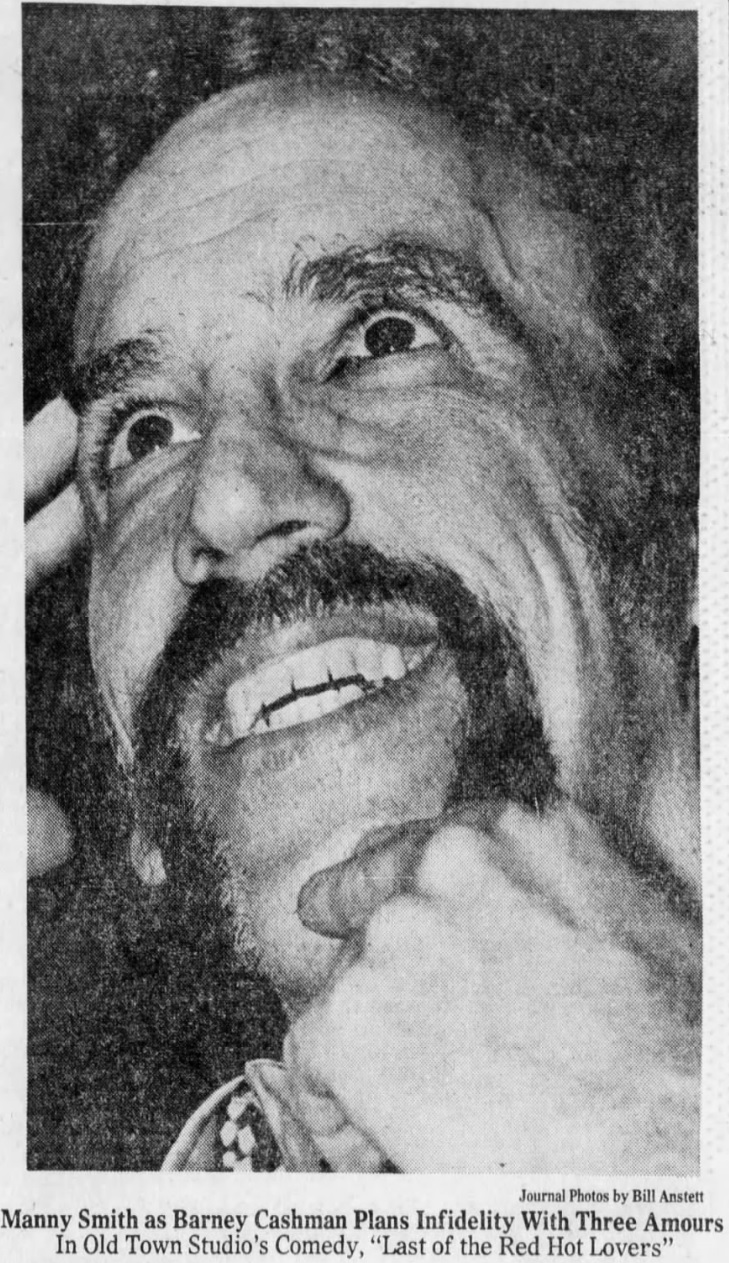

Ah. Here’s a picture of him on stage, wearing a rug.

The Albuquerque Journal, Thursday, 14 March 1974, p. C1.

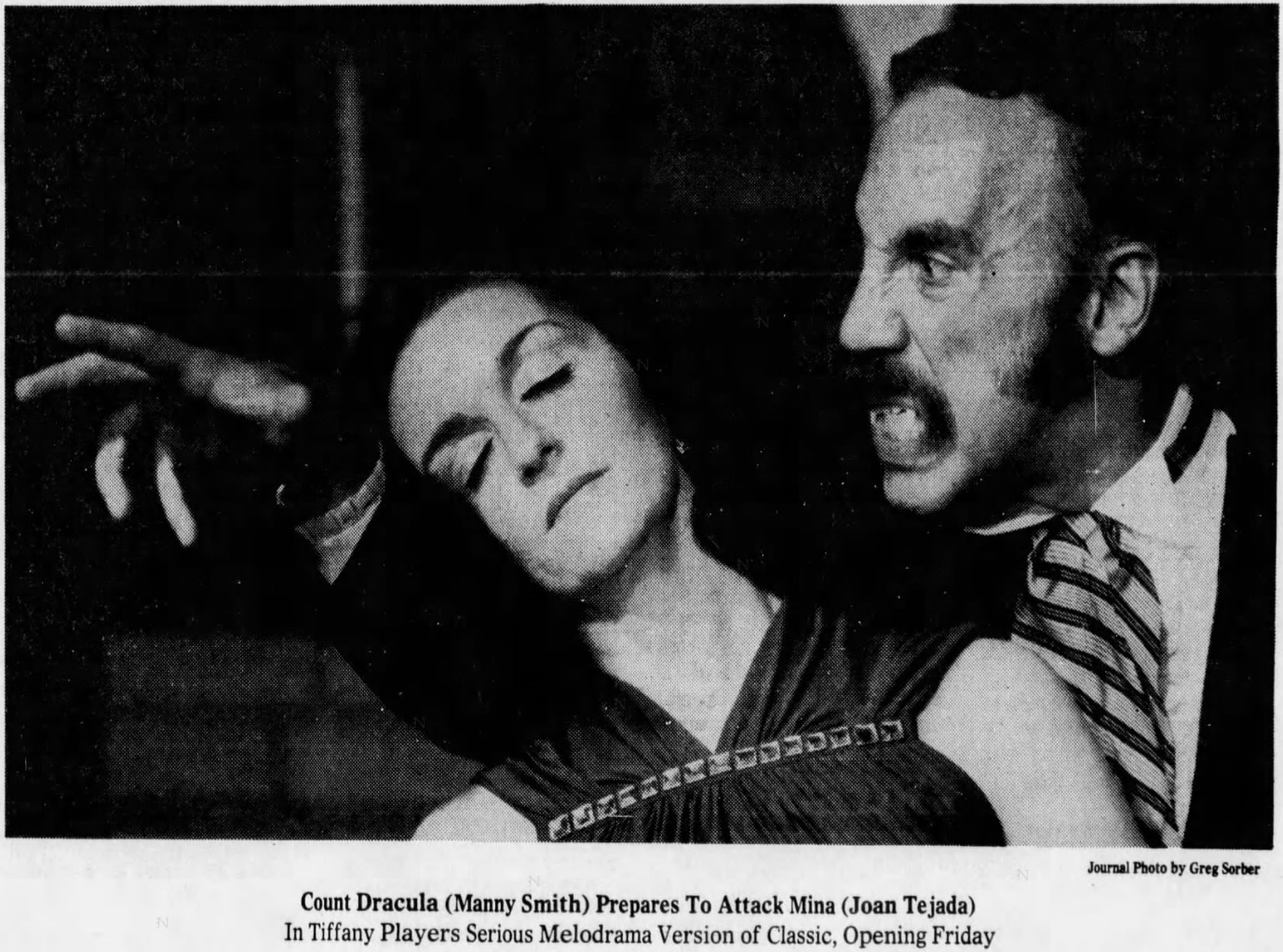

Another stage rôle.

The Albuquerque Journal, Thursday, 19 June 1975, p. C1.

Back to the story.

Mr. Smith invented a game to teach us the Greek alphabet, albeit with an appalling American mispronunciation.

The game was simple.

We would have a contest, and whoever could recite the Greek alphabet the fastest would win a piece of hard round candy,

which Mr. Smith for some reason called a “sparkle.”

That was my introduction to the alphabet, and I practiced, practiced, practiced, aloud, at home, but only if my father was away,

because he would blow up at any disturbance, and, in his view, everything was a disturbance.

(To survive in his presence, I had to act as though I did not exist.)

My mother heard me and asked what on earth I was saying.

I told her it was the Greek alphabet, and she said No, what I was saying was horrible.

Of course it was horrible, I explained, because I was speaking it as rapidly as I could.

No, she said, it was horrible, and she taught me the correct Modern Greek pronunciation.

Trigger. That’s the sort of thing that sparks my interest with all the force of dynamite.

I eagerly learned the correct pronunciation from her.

Unfortunately, though she could understand the occasional simple sentence of Greek, she could not speak the language at all.

Darn it!

From the moment she taught me the correct pronunciation, there was nothing else in the world I wanted to study except for that language.

Little did I realize that there would be no opportunity to learn it.

But I won the sparkle.

Paradoxically, the one and only sentence of Greek that Mr. Smith knew,

“Θέλω ἕνα ποτήρι

νερό,”

he pronounced in perfect Modern Greek.

He read to us aloud large swathes of The Odyssey, which enraptured me.

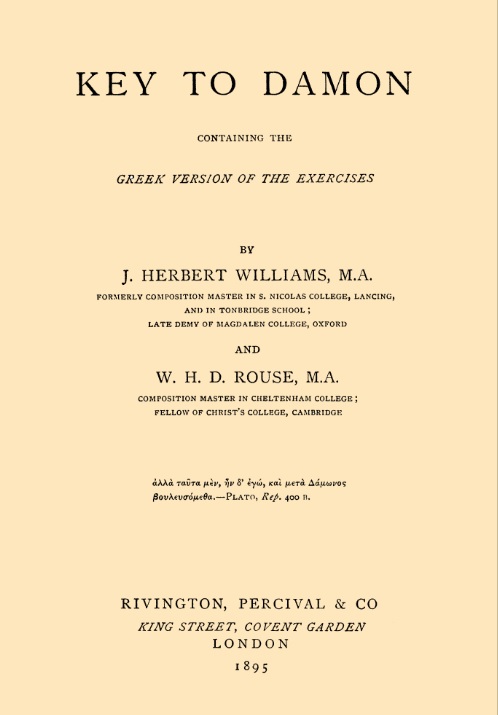

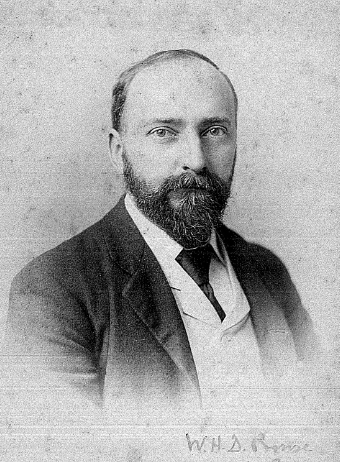

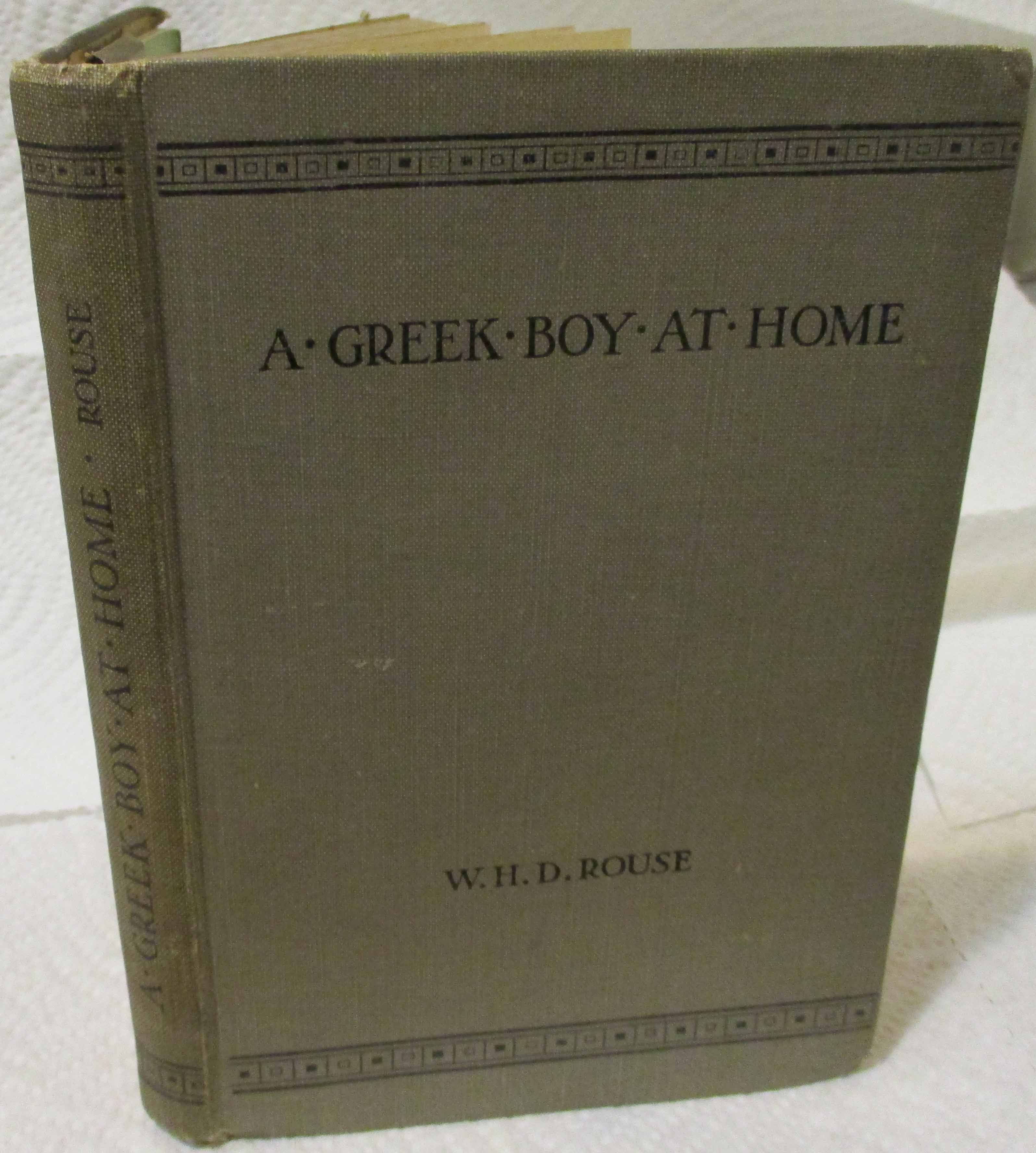

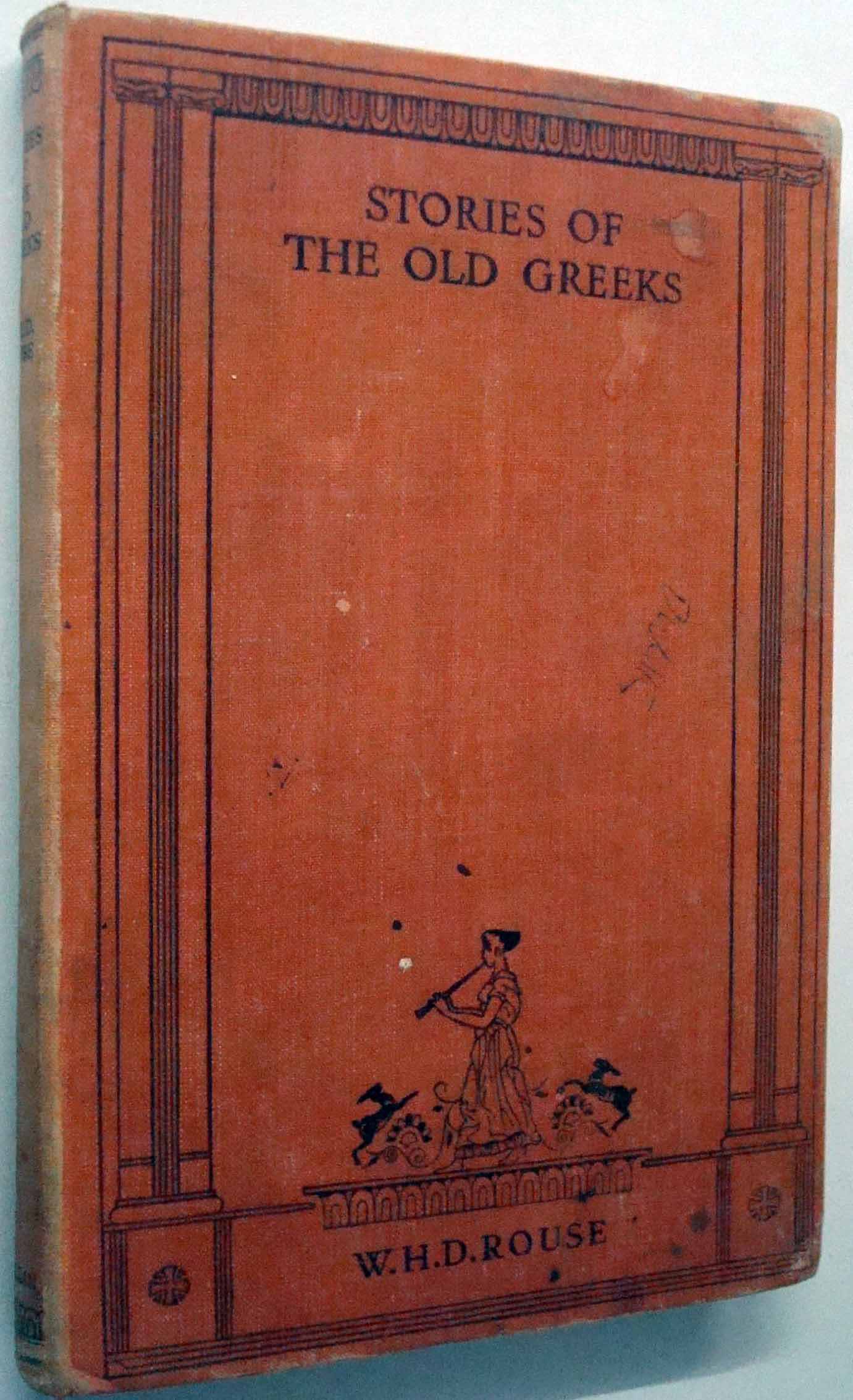

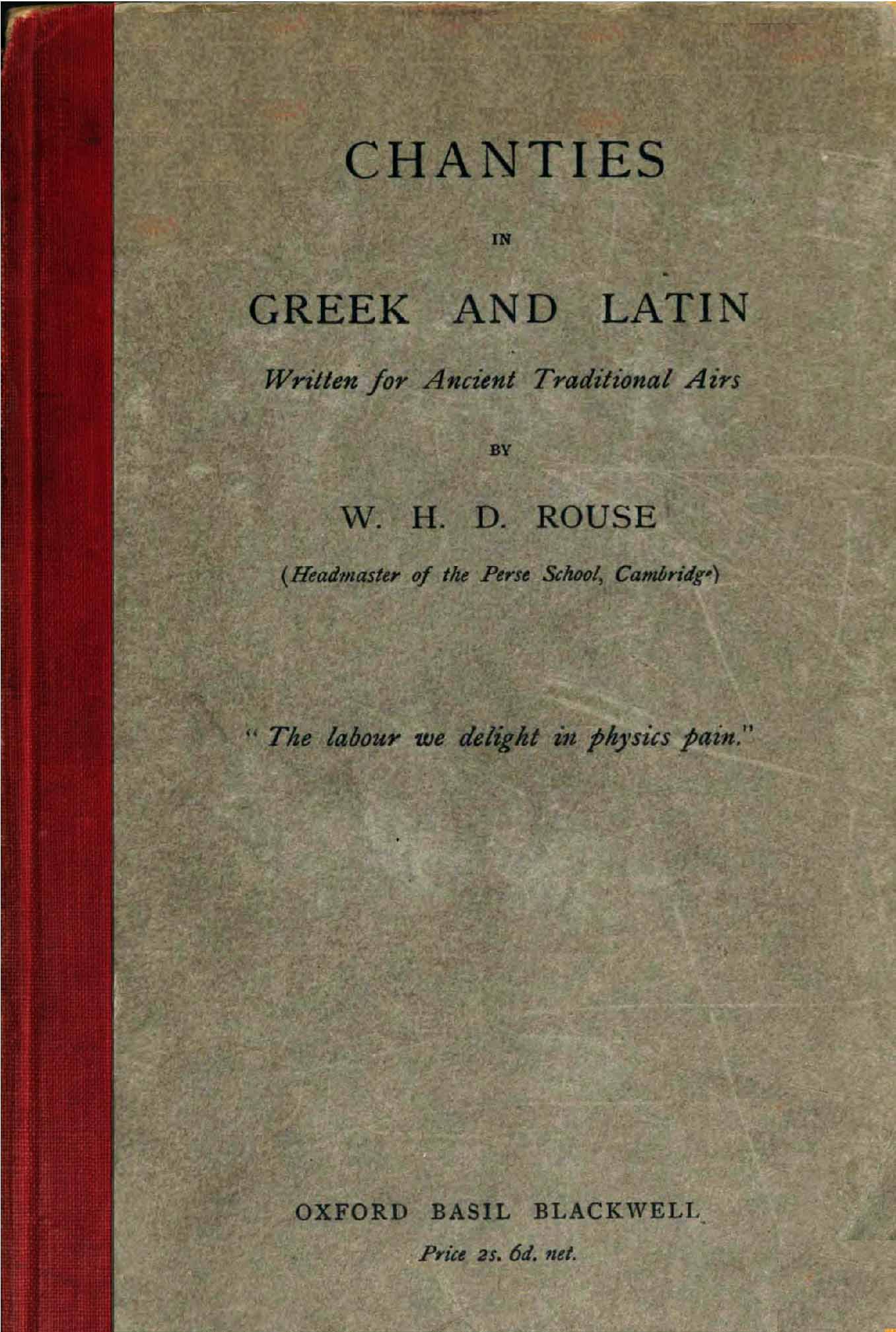

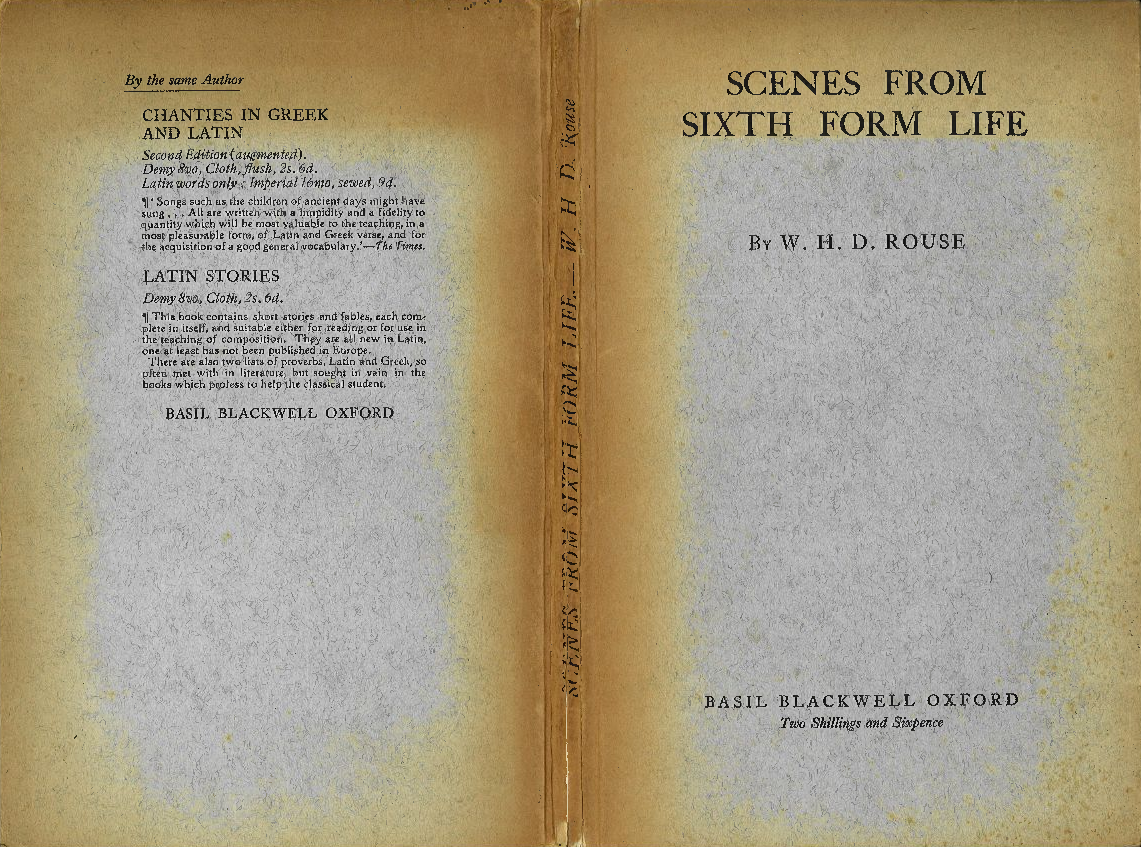

Looking back on it, I think he was reading from the Mentor/Signet paperback edition of Rouse’s translation.

Actually, I’m certain that was the edition he used.

Further, he told us amusing stories about the ancients, and I was on the edge of my seat.

His stories had me salivating for more — but there was no more.

When he finished his stories a week or two later, that was the end of that.

It was time to move on to something else.

There was no place to turn to continue. School library? No. Neighborhood library? No.

That brief glimpse at the Classical world was a tease, one that drove me nearly mad.

The resulting frustration has never left me.

At the beginning of the year I sang praises to Mr. Smith and I loved attending class.

He had a wonderful sense of humor and had me almost rolling on the floor.

Better yet, he was buddies with

George R. Fischbeck, who visited class for a failed “experiment” involving balloons and who autographed my notepad.

Dr. Fischbeck was a weatherman on Channel 4 and he was also the lab-coat-wearing host of Science 6, a science show on the educational channel,

KNME-TV 5 , for use in sixth-grade classrooms.

He was so much fun, with his silly mustache-wiggles and off-beat sense of humor.

He also sometimes popped up on the companion music show for classroom use, predictably called

Music 6, hosted by Nancy Johnson,

and I’ll never forget the Nancy/George version of “There’s a Hole in the Bucket.”

Channel 5, always hurting for funds, re-recorded all its quad tapes and ¾" tapes 70 times and more,

by which time the oxide had all fallen off.

So, in all likelihood not a single moment of those shows still exists anywhere.

Talk about a loss. (If anybody has any of these episodes, please write to me. Thanks!)

People tuned in to the Channel 4 nightly news just to get their giggles from watching this guy.

Dr. Fischbeck was in love with Albuquerque (Al buh kyoo er kyoo as he called it one day on Science 6)

and steadfastly vowed never to leave —

until a talent scout for Channel 7 in Los Ángeles discovered him and lured him away with promises of endless wealth.

The entire city was so sorry to see him go.

Mr. Smith was also responsible for the destruction of my New York accent (the accent peculiar to Westchester County).

The other kids gently poked fun at me, and I had no idea why.

Mr. Smith put this to rights, and he spent probably an hour or so entertaining us with the various accents

found in and around New York City and Long Island.

Once he demonstrated all the differences — Bronx versus Brooklyn versus Manhattan versus Long Island and so forth —

and had us kids screaming with laughter, tears rolling down our faces,

I could, for the first time in my life, hear the differences,

and I could, for the first time in my life, distinguish the standard Kansas City-based prime-time-TV accent.

After that hour or so, I had a Kansas City-based prime-time-TV accent.

From that day to the present, I could not even mimic my old accent.

Many moons later, when a friend and I traveled to and from NYC in 1996, we stopped to get a bite to eat at a restaurant in Hastings-on-Hudson,

and our waitress, who looked so much like a classmate from kindergarten through third grade, had exactly my childhood accent.

I thought she was my old classmate, but alas, she was not, and her name, Katie, didn’t match.

I so much wanted to ask her to sit with us for 30 minutes just so that I could listen to her and see if I could imitate her speech,

but, of course, that was impossible.

She was busy, and even if she weren’t, I doubt she would have taken kindly to such a request.

Back to class.

From being one of Mr. Smith’s best students at the beginning of the school year, I quickly became by far his worst.

All I did was sit and stew with resentment and had not another kind syllable to say about my teacher.

Something called “discipline,” by the way, is the worst thing you can do for a student who is bored to distraction.

Take it from me.

It is not only discipline directed towards me that I resent; I resent discipline directed towards anybody.

(To this day I feel so sorry for a fellow student named Vicky. It was that day that I saw the dark side.)

Well, admittedly, it wasn’t solely the frustration that converted me into the worst student.

It was home life as well, as I can now finally see.

My father refused to allow me to do my homework for the first month or two, which killed my grades dead.

From the time I got home at about 3:30 until the time he ordered me to bed at 9:00,

he would lecture me, nonstop, faulting me for everything under the sun.

At 9:00, he would demand to know if I had done my homework.

I would meekly confess, “No,” and then he would roar at me even more.

“Why didn’t you do your homework? You’ve been here since 3:30! What have you been doing all this time?!?!?!”

I was totally miserable, felt utterly defeated, and discovered, quite by accident, that I could escape his wrath

by the mere expedient of heading not to my room upon returning from the school bus,

but by heading instead to the room where the TV set was.

I would turn on the TV, and my father would stay in his room, silently devoting his time to reading get-rich-quick books, and all was relatively peaceful.

So, I devoted all my time to the worst TV shows just to tune everyone and everything out.

At the time, I didn’t understand the reason for my change in behavior.

I just thought I had discovered lots of good TV shows that deserved careful attention.

When I look back on it all, four decades later, it’s as clear as a bell.

Anyway, before I knew it, I was addicted. I learned that TV is the hard stuff, dangerous to the nth degree.

The occasional Man and the City or educational program, okay, but once you find yourself obsessing over the tube, you need to quit, cold turkey.

Here he is as his own peculiar interpretation of Dracula.

The Albuquerque Journal, Thursday, 29 September 1978, p. C1.

A few years later I visited Mr. Smith again, in his classroom after school hours, and we finally hit it off.

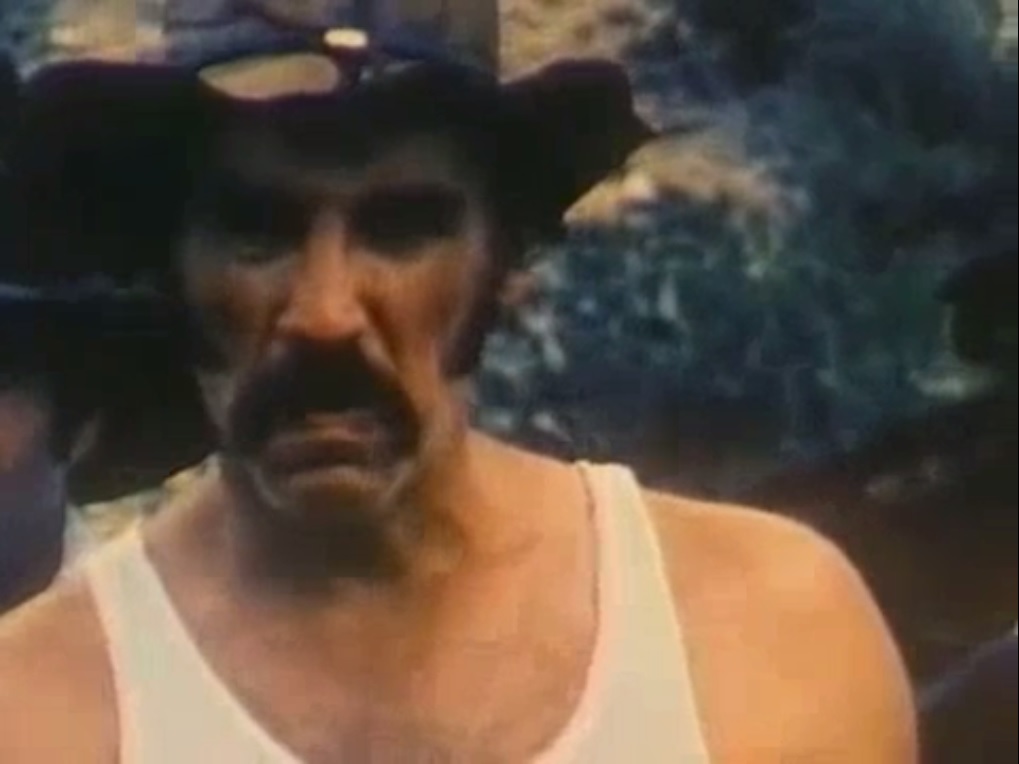

Then I saw him perform a campy Dracula on stage and later he popped up in a bit part with John Carradine in an abysmal flick

called either Monster or Monstroid

that went straight to VHS, where it was hosted by Elvira, Mistress of the Dark.

Oh, here it is.

Download it before it disappears.

That ain’t his voice. No idea who dubbed him.

My heavens! His voice could almost rival that of Christopher Lee,

and so filmmakers either told him to do silly accents

or they got somebody to dub him.

Go figure.

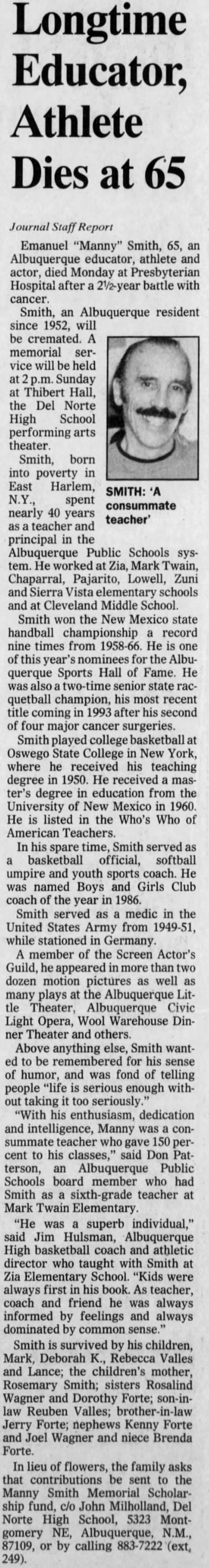

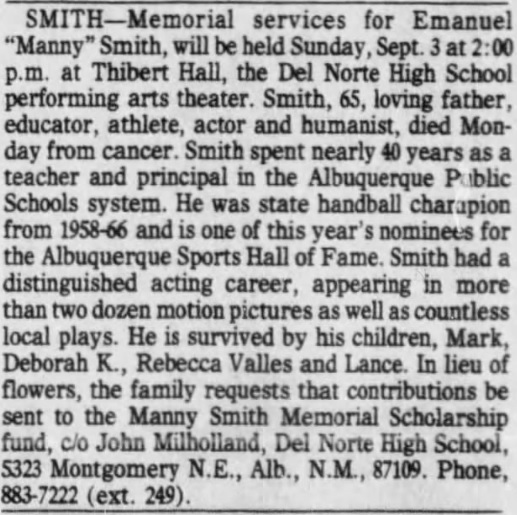

In my memory it was only months afterwards, but in fact, now that I check, I see that it was decades afterwards that the newspaper reported that he had died.

He wasn’t even old.

The Albuquerque Journal, Tuesday, 29 August 1995, p. C2.

The Albuquerque Journal, Friday, 1 September 1995, p. D15.

By the time I was eleven, the only surviving Greek relatives were my grandmother and great-grandmother .

From the time I was born, my parents moved repeatedly just to get away from them,

and each time we moved, they would move next door to us.

At age eleven, we were in Albuquerque and they stayed behind in Mount Vernon, New York.

Sigh of relief.

Then, when I was twelve, they moved in with us.

In school, one of the many issues that bothered me

was the Greek world and the Roman empire being covered almost every autumn with a week or two of insipid narratives.

The teachers (except for Mr. Smith) and the texts made the ancients an unfathomable enigma, entirely unhuman.

Worse, those dreadful illustrations, supposedly designed to show us what ancient Greece and Rome looked like, made the topic entirely alien.

This may as well have been another species in another galaxy.

I couldn’t relate, but I wanted to.

I couldn’t articulate the problem at the time, but now I can:

I resented real people being distanced from me, from my understanding, from my emotions.

I resented having them depicted as something other.

That bothered me. The descriptions and illustrations were nightmarish.

I wanted to humanize the ancient Greeks and Romans, else I would continue to live inside a nightmare.

I wanted to dig in, and I thought the best way would be through the actual literature.

Oh, if only Mr. Smith had just told me about Edith Hamilton’s seductive book, The Greek Way.

If only he had shown me where I could learn conversational Classical Greek. Ohhhhh....

There was also a further ingredient that got me interested, and this was a further trigger:

The way teachers pronounced the letters of Greek alphabet in school, for math class and so forth,

and the way they pronounced the occasional Greek root of an English word,

was so dreadful, so totally wrong in every way, that I cringed in agony.

I was determined to set this right once and for all.

’Twas a childish ambition.

In tenth grade, age 15, I elected Latin class and took two years’ worth.

I would have preferred Greek, but Greek was not taught in school.

So, Latin would have to do.

After all, Latin and Greek were the two major languages in the Roman empire, and so it would be a nice start, I thought.

Then came the shock.

As with all the other students in the class, I came out of the second year knowing nothing.

We could not speak, understand, read, write, or even translate Latin.

To my surprise there was no Latin conversation. None. Not a sentence of Latin conversation. Not even once. Never.

I assumed, like all the other students seemed to assume, that once we had mastered the basics, we would begin to talk.

Wrong!

You see, our teacher emphasized the importance of grammatical terminology

as well as the technical names of all noun and verb endings.

We all got passing marks because we could distinguish a third-declension noun from a first-declension noun

and because we could distinguish an ablative from an accusative.

Not one of us could understand a sentence, though.

Our job was to translate into English, not aloud, but only on paper.

At first the stories were simple.

After we studied countless paradigm charts and learned endless grammatical terminology,

and as we were being drilled and tested relentlessly on this material,

our teacher (who shall remain nameless) assigned us a simplified version of “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” reduced to six short paragraphs,

as it appeared in our textbook.

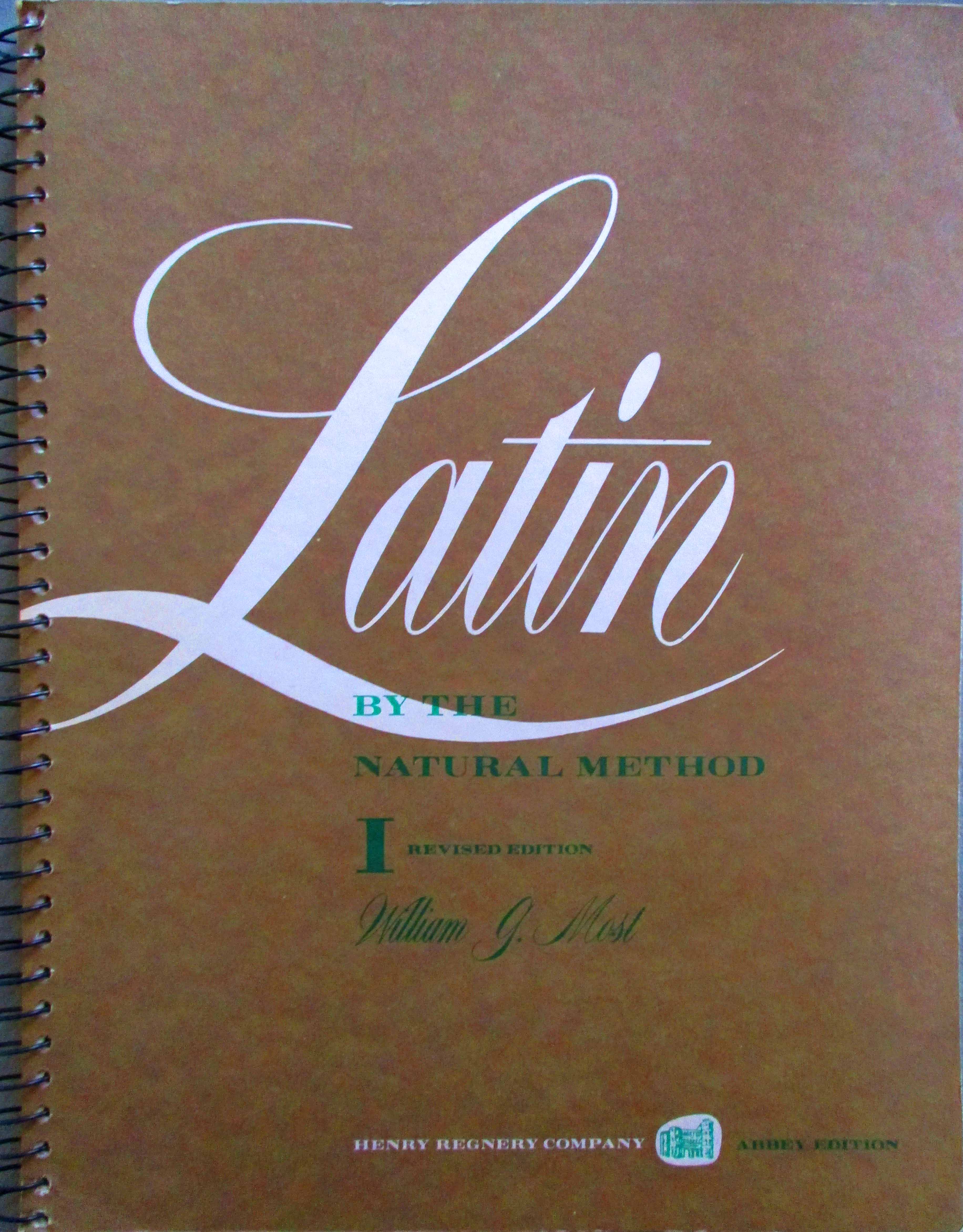

What was that textbook?

Hmmmmm. Let’s explore. What Latin texts were used in high schools back in the 1970’s?

Web searches revealed the popular titles.

Was it Ullman/ Henry’s

Latin for Americans I and II (Macmillan)?

Was it Hines/ Welch’s

Our Latin Heritage I, II,

III,

IV, (Harcourt Brace)?

Was it Breslove/ Hooper/ Barrett’s

Latin: Our Living Heritage I and II (Charles E. Merrill Publ.)?

Was it Burns/ Medicus/ Sherburne’s

Lingua Latina I and II (Bruce Publ.)?

Was it Crabb’s

Living with the Romans I and II (Lyons & Carnahan)?

Was it Jenkins/ Wagener’s

Latin and the Romans I and II (Ginn)?

Was it Page/ Beckett/ Rutherford’s

Gateway to Latin (Gage)?

Was it Gould/ Whiteley’s

A New Latin Course I and II (Macmillan)?

Was it MacNaughton/ McDougall’s

New Approach to Latin I and II (Oliver & Boyd)?

Was it Jenney/ Smith/ Thompson’s

First Year Latin (Allyn and Bacon)?

Was it Sweet’s

Latin: A Structural Approach (U. of Mich.)?

Was it Taylor/ Prentice’s

Our Latin Legacy (Clarke, Irwin & Co.)?

Was it Taylor/ Prentice’s

Living Latin (Clarke, Irwin & Co.)?

I couldn’t remember.

They did not look familiar, not even a little bit.

What was it?

A ha! I just visited a book shop and there it was!

What a coincidence! I hadn’t seen this since 1977,

and as soon as I wonder about it in early 2016, there it suddenly is, right in front of my nose!

Is the universe trying to tell me something?

Annabel Horn, John Flagg Gummere, and Margaret M. Forbes, Using Latin,

(Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Company),

Book One (1961) and

Book Two (1963).

Bingo! Five bucks a volume, and each volume was unused, unread, brand-new condition though the paper had inevitably aged.

The hinges were still stiff. These two volumes had never been opened.

These were promotional copies, and tucked inside the front cover of Book Two was an advertisement boasting the virtues of the course.

I couldn’t resist and purchased the set.

My memory is that our teacher selected certain exercises and skipped around,

that she only used Book One, and that in two years of schooling, she never even had us finish that first volume.

We never saw the second volume.

Now that I’m looking through these two volumes, I see that my memory was right.

We were not to speak “The Ant and the Grasshopper” aloud. We were not to have a class discussion about it.

We were to translate it into English, with pen and paper, in our 55-minute class time.

To get some air into our lungs, our teacher walked us out of the classroom and sat us down on a sports field nearby,

breaking us up into five or six groups.

Though “The Ant and the Grasshopper” was the simplest Latin imaginable,

we were reduced nearly to tears at our inability to make sense out of any of it.

Even such a basic statement as “Tu pigra es!”

elicited gales of laughter from those who attempted to force it to make sense:

“You lazy es!” Unforgettable.

Am I saying that I immediately understood that three-word sentence? No. It gave me enormous difficulty.

As a matter of fact, all 30 or so students in the class labored mightily over that three-word sentence.

Not one of us could understand it on first reading — or even on tenth reading.

“Pigra” was in the dictionary at the back.

Most of us remembered that “tu” meant “you,”

but nobody could find “es” in the dictionary at the back of the book.

After maybe five minutes I finally remembered that “es” followed “sum” and blurted that out to everybody in my group. Ah!

At long last we deciphered that sentence.

Why did it give us such difficulty?

You see, we had by then been trained on nominative and accusative singular; subject; direct object; predicate noun/adjective;

ablative with preposition; plural nouns; verb endings in -t and -nt; ablative/accusative with prepositions;

apposition; position of adjectives; case uses; words ending in -ia, -tia/-cia, -ula; genitive case; tense;

forms of sum; person; number; dative case; indirect object; dative with adjectives; masculine nouns in -a;

declension I cases and case uses; first and second conjugations; infinitives; present stem/tense.

Oh heavens above. No wonder nobody could get a grasp of the language.

With painstaking analysis, we could name the forms we were looking at.

We could reproduce these charts in our sleep — actually, I think I did.

We could hic-hæc-hoc-huius-huius-huius-huic-huic-huic-hunc-hac-hoc-hōc-hāc-hōc-hī-hæ-hæc-hōrum-hārum-hōrum-hīs-hīs-hīs-hōs-hās-hæc-hīs-hīs-hīs-ipse-ipsa-ipsum-ipsīus-ipsīus-ipsīus-ipsī-ipsī-ipsī-ipsum-ipsam-ipsum-ipsā-ipsā-ipsō-ipsī-ipsæ-ipsa-ipsōrum-ipsārum-ipsōrum-ipsīs-ipsīs-ipsīs-ipsōs-ipsās-ipsa-ipsī-ipsī-ipsī

with the best of them, we could recite these charts until we turned blue in the face, but to what avail if we never practiced using the language?

What would it profit foreigners in an English class to learn nothing but such chart forms as the following?

INDICATIVE Present: I do, you do, he/ she/ it does, we do, you do, they do.

Preterite: I did, you did, he/ she/ it did, we did, you did, they did.

Present continuous: I am doing, you are doing, he/ she/ it is doing, we are doing, you are doing, they are doing.

Present perfect: I have done, you have done, he/ she/ it has done, we have done, you have done, they have done.

Future: I shall do, you will do, he/ she/ it will do, we shall do, you will do, they will do.

Future perfect: I shall have done, you will have done, he/ she/ it will have done, we shall have done, you will have done, they will have done.

Past continuous: I was doing, you were doing, he/ she/ it was doing, we were doing, you were doing, they were doing.

Past perfect: I had done, you had done, he/ she/ it had done, we had done, you had done, they had done.

Future continuous: I shall be doing, you will be doing, he/ she/ it will be doing, we shall be doing, you will be doing, they will be doing.

Present perfect continuous: I have been doing, you have been doing, he/ she/ it has been doing, we have been doing, you have been doing, they have been doing.

Past perfect continuous: I had been doing, you had been doing, he/ she/ it had been doing, we had been doing, you had been doing, they had been doing.

Future perfect continuous: I shall have been doing, you will have been doing, he/ she/ it will have been doing, we shall have been doing, you will have been doing, they will have been doing.

Would a student be able to purchase groceries with such a skill? Read a book? Listen to the news? Chat over a dinner with a friend?

Yes, we need to know this, but this is not the be-all and end-all of the language,

and we cannot learn it by rote memorization, but only by everyday use.

No conversation. No practice. Just forms and charts and pen-on-paper mistranslations together with the occasional vocabulary tests

and the requisite fill-in-the-blanks-yeah-I’ll-tell-you-what-you-can-do-with-those-blanks exercises.

We had not been taught how to make sense out of any of what we had learned.

We had not been taught how to put this knowledge together to express thoughts.

As I said before, and as I shall say again, there was no Latin conversation.

Think about it. Think think think.

If you’re reading this web page, you are fluent in English.

I bet you cannot tell me how many conjugations there are in English.

I bet you cannot tell me how many declensions there are in English.

I bet you cannot chart an English verb or an English noun.

I don’t know how many conjugations and declensions there are in English,

and I can’t chart English verbs or nouns either.

Many people argue that there are no conjugations or declensions in English, and that English words are not inflected,

which, they kindly explain by way of excuse, is why native English speakers have difficulty learning inflected languages.

English isn’t inflected?

Then what the heck is that fragment of a chart I reproduced above?

What a load of dingo’s kidneys!

English IS inflected!!!!!!

Many languages splice the inflections onto the ends of the words.

English usually staples them onto the beginnings, though in writing we leave a space before the root.

You don’t believe me. Okay:

| vocāre | to summon |

| vocō | I summon |

| vocās | you summon |

| vocat | she summons |

| vocāmus | we summon |

| vocātis | you summon |

| vocant | they summon |

| vocem | I may summon |

| vocēs | you may summon |

| vocet | she may summon |

| vocēmus | we may summon |

| vocētis | you may summon |

| vocent | they may summon |

| vocer | may I be summoned |

| vocēris | may you be summoned |

| vocētur | may she be summoned |

| vocēmur | may we be summoned |

| vocēminī | may you be summoned |

| vocentur | may they be summoned |

| vocātus sim | I may have been summoned |

| vocātus sis | you may have been summoned |

| vocātus sit | she may have been summoned |

| vocāti sīmus | we may have been summoned |

| vocāti sītis | you may have been summoned |

| vocāti sint | they may have been summoned |

| rana | frog |

| ranæ | frog’s |

| ranæ | to the frog |

| ranam | frog (direct object) |

| ranā | by the frog |

| ranæ | frogs |

| ranārum | frogs’ |

| ranīs | to the frogs |

| ranās | frogs (direct object) |

| ranīs | by the frogs |

See? English is inflected, and the inflections are pretty much as confusing as they are in other languages. I just picked up a learned tome by Thomas R. Beyer, Jr., entitled 501 English Verbs: Fully Conjugated in All the Tenses in an Easy-to-Learn Format. ¡Ay chihuahua! As I look through these conjugations, I’m at a total loss. What do they mean? “Express,” indicative, passive, past progressive: “I was being expressed, she was being expressed, you were being expressed...,” passive subjunctive present: “if I be expressed, if you be expressed, if they be expressed....” What on earth does that mean? Has anyone ever used such forms? Ever? “Hop,” passive voice, present: “I am hopped,” “you are hopped,” “we are hopped”; imperative mood: “be hopped”; subjunctive mood, future: “if I should be hopped,” “if you should be hopped”.... What? Who says such things?

Why do so many people insist that English is not inflected?

Answer: Because, in writing, we split the nouns and verbs with spaces between most of the varying inflections and the unvarying roots.

So, I suppose that if in Latin we were to write “voc ētur” and if in English we were to write “sheissummoned,”

we would conclude that English is inflected and that Latin isn’t. Whatever.

Let’s go further.

I bet you cannot identify which verbs and nouns are irregular.

I certainly can’t. I haven’t got a clue.

We do have irregulars, but I don’t know which ones they are, because they all seem regular to me.

(Oh, here’s one that just occurred to me: “go/went.”

Oh, and for a noun, we have “sheep” which serves as both singular and plural.

There are plenty of others. Heck if I know what they are.

I don’t want to see a list, because it would confuse me.)

I know we have more than one conjugation and more than one declension.

I don’t know what they are and I can’t tell the difference.

Yet I never make a mistake in these matters (unless I do so deliberately for satirical effect), and you probably don’t either.

So why, when teachers instruct us in another language,

do they abandon conversation in favor of all this meaningless technical garbage that not even native speakers know?

As has been proved, when a teacher discards all this gobbledygook and instead teaches conversation,

the students learn at lightning speed and nearly without effort.

We shall witness an actual demonstration in a link below,

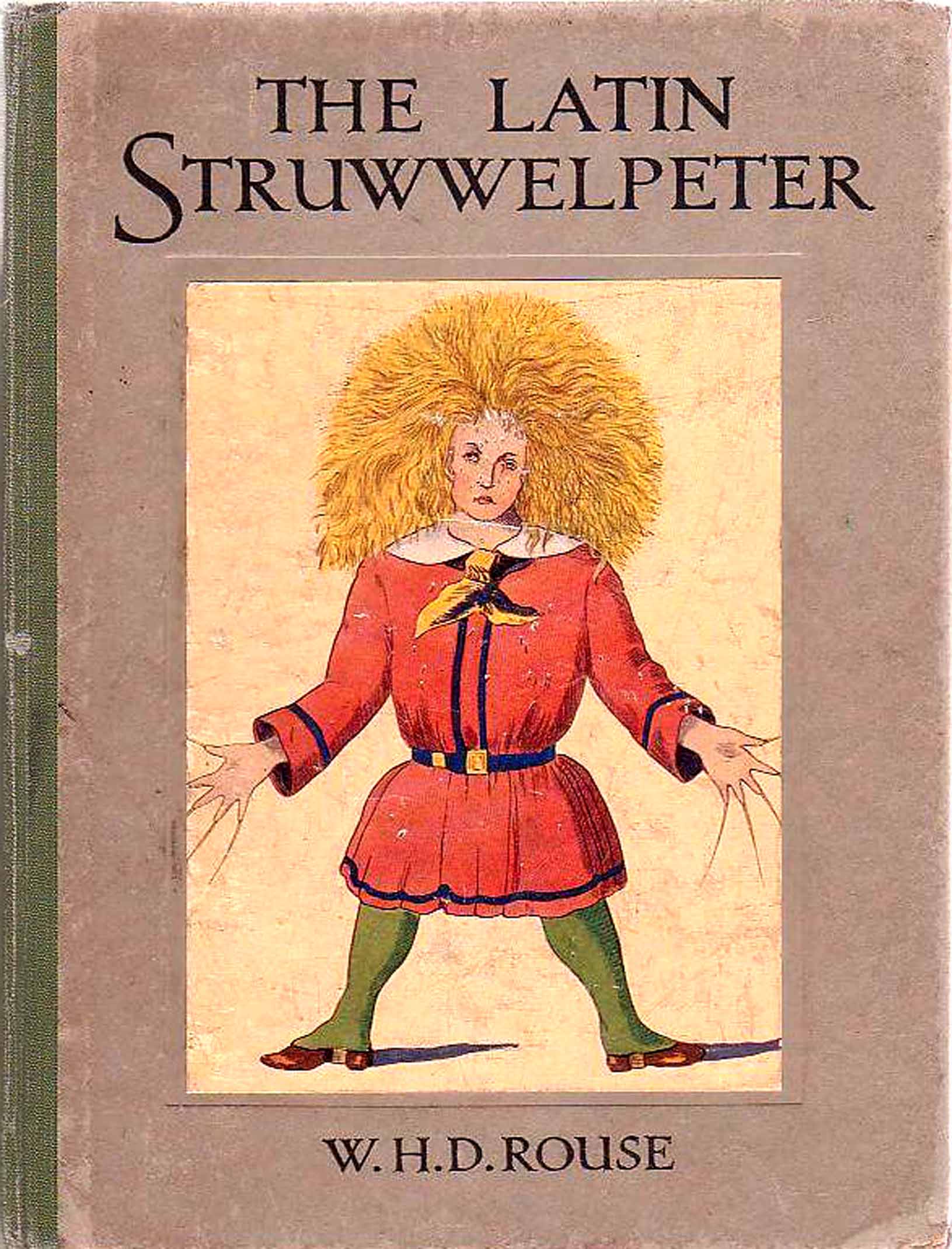

when we hear an antique recording of W.H.D. Rouse conducting a Latin class.

Why is a language taught without speaking?

How well would we be able to swim if, without ever getting into the water, our only instruction consisted of a 500-page book

on muscle movements and the correlative foot-pound pressures and pulse rates of swimmers, together with water-volume displacement, and if we were to memorize

the circumference and angle of each stroke and every technical term for every physical phenomenon,

upon which we would be tested during lengthy biweekly multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank tests?

This is how languages are taught.

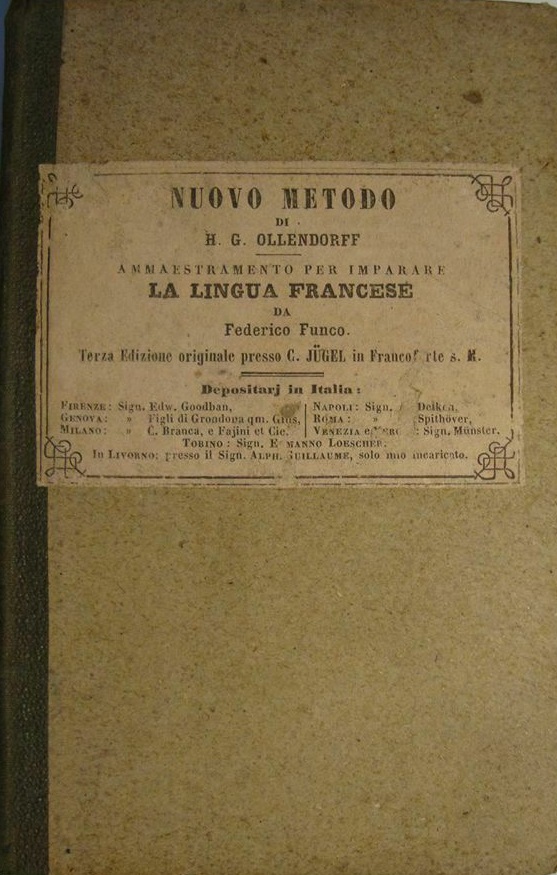

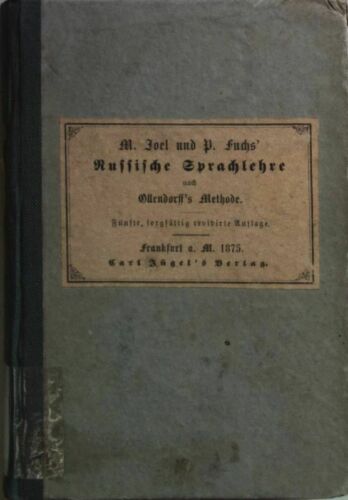

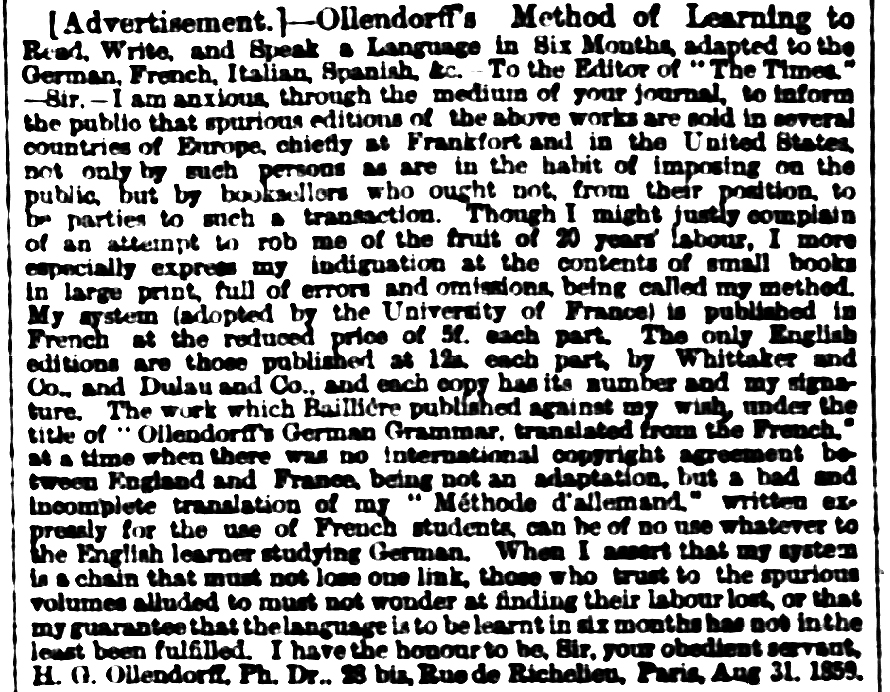

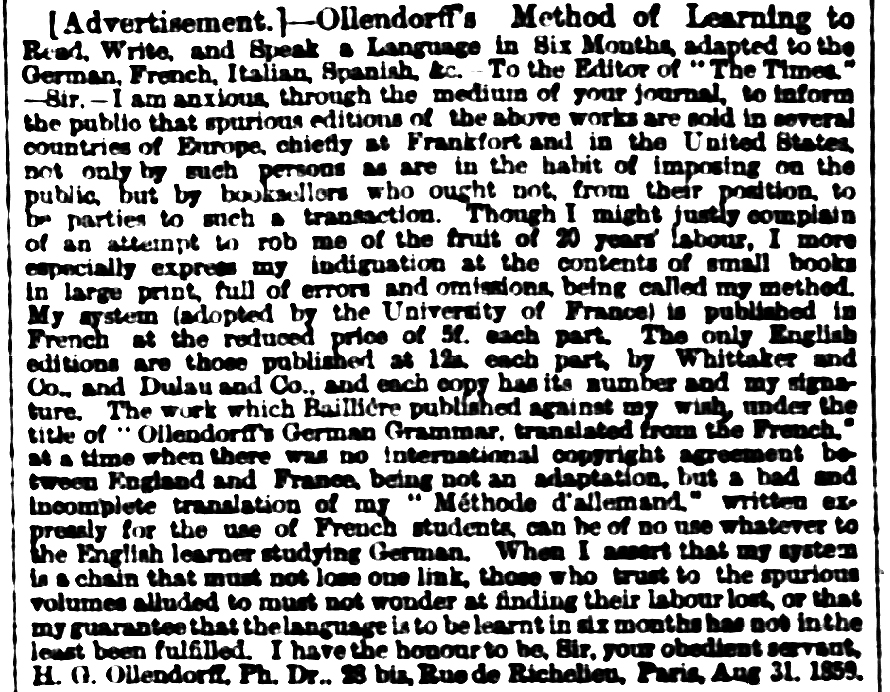

“Non val la pena d’ impararlo a leggere, senza impararlo a parlare.”

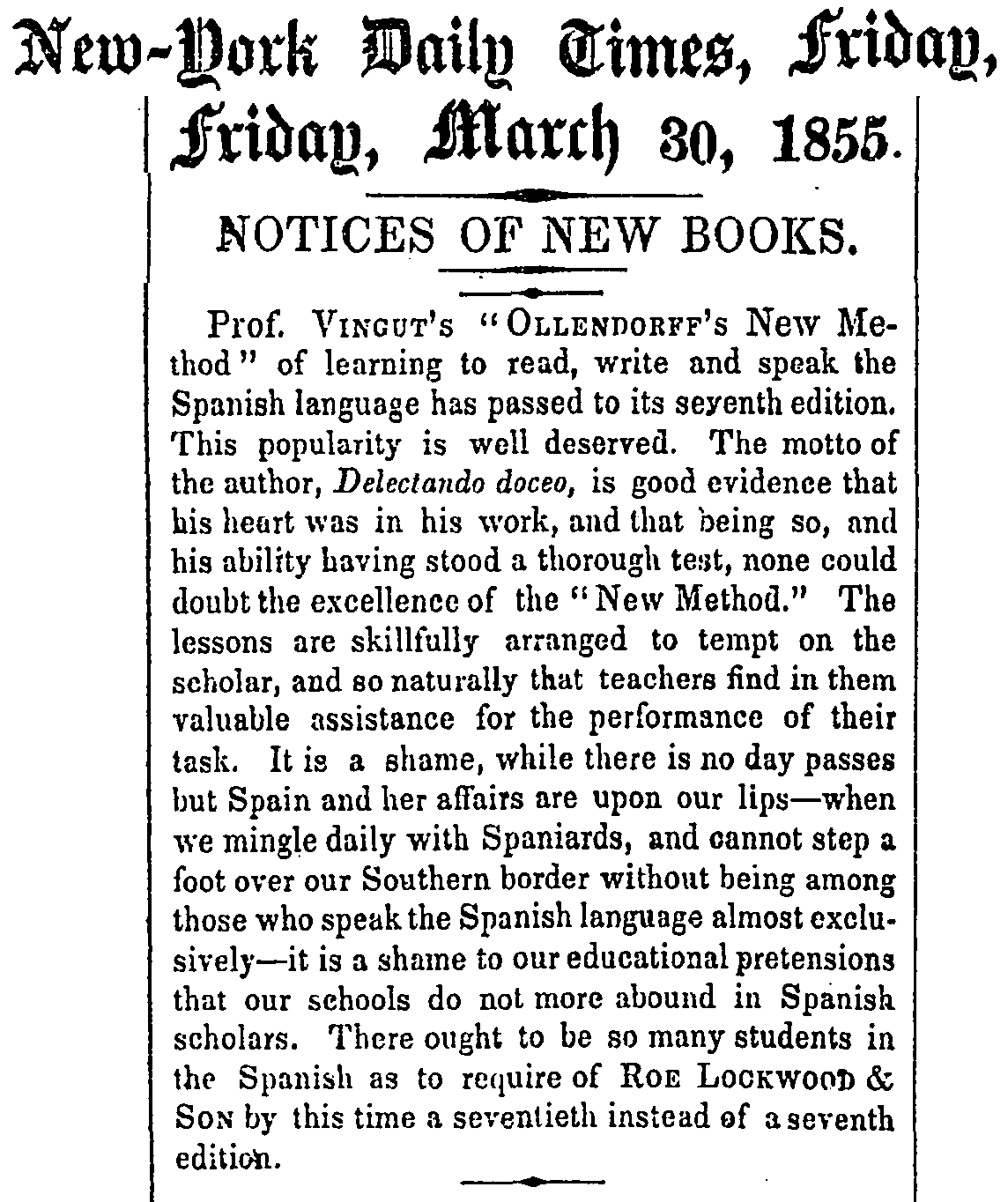

— H.G. Ollendorff (1846)

— H.G. Ollendorff (1846)

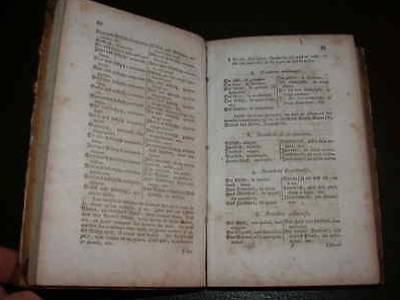

In looking through this Using Latin course again now, I see that it’s not terrible.

Not at all. Actually, I have to admit it, this course is pretty darned good,

much better than most courses I’ve run across.

The illustrations are lovely, and the English-language essays about Roman life and culture are splendid.

We skipped all of that.

On the other hand, the readings are dull, but they are fulsome,

and a creative teacher would be able to use this book as a basis for conversation.

A creative teacher, using this book, would have students speaking within the first minute of the first day of class.

Classroom conversation, entirely in Latin, would have been the key to understanding.

If, instead of having us painfully decrypt “The Ant and the Grasshopper” into English,

our teacher had conducted a one-hour conversation with all the students about it, entirely in Latin,

using only vocabulary we already knew, asking simple questions about the story,

that would have made a world of difference.

We all would have understood.

The thought never crossed the teacher’s mind.

That’s not the way she taught.

She would drill us mercilessly on paradigm charts of noun endings and verb endings,

assign us to do the multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank exercises with pen on paper,

and then have us translate the stories into English, with pen on paper.

She was satisfied when, after an hour in class, we managed torturously to translate a few sentences into English.

It was not her job to teach us to understand Latin, but rather just to decrypt it and render it into English.

The endless charts were the decryption keys. That, apparently, is why we needed to memorize those charts.

The goal, she said, was to improve our English skills.

That was the only stated goal — frustratingly incompatible with my personal goal of learning Latin.

She seemed to assume that understanding followed memorization of technical names and memorization of charts,

that the language would then be so obvious that conversation would be entirely unnecessary,

and that we would somehow figure it all out for ourselves — by what form of magic I do not know.

I was so embarrassed when the other kids in school, upon discovering that I was in Latin class,

would request, “Say something in Latin!”

I couldn’t. No Latin student could.

We never spoke a sentence of Latin in class; we seldom even spoke a word,

but we could recite the verb endings and the noun endings.

Not long after “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” we were assigned texts of considerably greater difficulty.

“Colui che vuol insegnare un’ arte deve conoscerla a fondo;

bisogna che non ne dia che le nozioni precise e ben diregite;

bisogna che le faccia entrare ad una per una nello spirito dei suoi allievi,

e sopra tutto bisogna che non sopraccarichi la memoria loro di regole inutili e vane.” — H.G. Ollendorff (1846)

I’m looking through this Using Latin book some more.

If students would simply ignore their teachers and work their way through this book leisurely,

reading the stories aloud over and over and over and over and over and over again until they become as easy as English,

then students could learn the language through this course.

Skip the multiple-choice and fill-in-the-blank exercises, please.

Skip the numerous sections about Latin roots of English words, please.

Other than that, the book is fine.

Rather, I should say that it is about as fine as such a book could possibly be.

I wish language courses would be taught without books, without writing.

There should be only speaking. Students should not see anything written until after they’re speaking with confidence.

Even with a good book, though, the problem is that the class work and the homework consisted only of written translations and fill-in-the-blanks.

In my view, translation should be forbidden. The students should simply speak Latin in class.

English should be used only sparingly. By the end of the first semester English should be dropped altogether,

and class should be conducted entirely in Latin.

That would solve all the problems in a moment.

That isn’t done, though, ever.

The normal excuse is that it is literally impossible to speak a dead language.

Drop that lame excuse. Latin is not a dead language.

It has been continuously spoken for over two thousand years.

It’s no longer a native language, but it’s not dead by any means.

Speaking, though, is not what happens in any course.

Translation is the rule — the only rule.

So, students labor through a lesson and stop, dead exhausted, when the homework assignment is finally finished at eleven at night.

That is so wrong.

That method is entirely counter to the goal of the Using Latin book.

It is amazing to me that, using a text like this, our teacher was able to render the language incomprehensible.

She was typical, though. I doubt there was ever a teacher anywhere who, using Using Latin, did it any differently.

Our teacher should have named her course “Misusing Latin.”

The homework, which converted simple readings into impossibly difficult readings, should never have been given.

If the subject — any subject — cannot be covered in class time, then homework cannot make up for the deficit.

Homework is nothing more than useless and unproductive labor, much like Bentham’s Panopticon.

It is designed to keep idle hands busy and to bore students nearly to death.

As such, it’s a great way to flunk out the brightest students (whose minds are too active to endure tedium)

and to heap all credit onto mediocre students (who have no problem with mindless tedium).

If class were taught well, no homework would be necessary or helpful in any way at all.

Let’s think about homework for a minute.

School begins at eight in the morning and ends at about three-thirty in the afternoon:

seven and a half hours, usually six classes a day, to which must be added travel time, an average of about 30 minutes each way.

So, say school is eight and a half hours per day.

Each class demands about one hour of homework a night.

Eight and a half plus six equals 14+ hours a day that students need to take copious notes as boring teachers drone on and on

and then suffer through boring reading and writing exercises in the evening.

Homework is doubled or trebled for the weekends.

When I was in school, I thought that was a bit much.

(Home life was, if anything, even more maniacal than school life,

and so for the sake of my sanity I would skip homework and sometimes even skip class just to get a breath of fresh air,

chat with a friend, see a Lloyd or Chaplin movie at the Sunshine Theatre,

stroll the streets in downtown to admire the old architecture that nobody else noticed, read a Dostoyevsky novel,

something, anything, to escape the madness for a few hours.

I could never catch up on missed lessons, my grades suffered, and that led to countless panic attacks.

My attitude was horrible, I was about as approachable and snuggly as a cactus,

and there is good reason that a number of people disliked me intensely.)

With such a schedule, it is impossible to lose oneself in any topic.

Learning can happen only by losing oneself, and school forbids that.

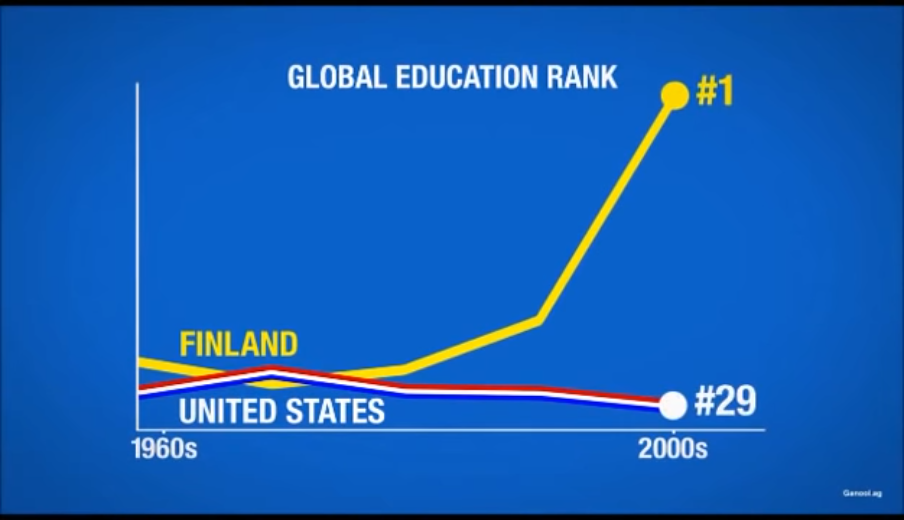

“Why Finland Has the Best Education System in the World,”

https://youtu.be/nHHFGo161Os

So there.

I have had this DVD sitting on my shelf for years but never watched it.

Then I discovered this sequence posted on YouTube.

I guess I should have watched that DVD.

Now let’s return to “Tu pigra es!”

Even without ever having learned the technical names of formal second-person present singular, emphatic personal pronoun, and so forth,

anyone raised speaking English can, by the age of three, easily understand the sentence, “You’re lazy!”

or even “Lazy you are!”

Nobody needs to know how to chart the phrase and break it down and provide the technical name for each part of speech

in order to speak such an impromptu sentence or to understand it.

We don’t — and shouldn’t — learn the technical linguistic terms

until after we know how to speak with ease.

The linguistic studies are to refine our understanding of a language we already speak fluently.

Latin class was all backwards.

I did not understand this at the time.

I just thought I was stupid. I was embarrassed half to death by my stupidity.

For two whole years I kept trying harder and harder and harder not to be stupid anymore.

The harder I tried, the harder I failed.

Looking back on it, how I wish someone had simply given me the simplest advice:

“Go over the first volume again, beginning on page one, and read each story twenty or thirty times over, aloud,

until it becomes as easy as English. Take your time. Don’t rush. Do it over summer vacation.

You’ll be surprised at the result. It’s like magic!”

There was no such advice.

Two years did I suffer failure after failure after failure, each worse than the last, as the class got harder and harder and harder.

We would spend hours — in groups! — attempting to translate a mere few lines.

A week or more could go by, in sheerest torment, before we succeeded in translating a single paragraph into English,

only to discover upon submitting our result that we had translated it incorrectly (only the teacher had the answer book).

In succeeding years, I looked into various language courses taught in schools and universities and even enrolled in a few.

They are all backwards.

The students never learn to speak the languages they are studying.

The rare student who is rich enough to spend a year or so in the country of choice, of course, comes back with fluency.

The majority who do not have that luxury conclude that they have no talent for languages.

Just discovered there was also a

Using Latin Book Three in 1968. Never seen a copy. I have one on order.

22 February 2016: Just arrived. As-new condition.

Wow. Impressive. Previous editions were copyrighted in 1939 and 1954. Who knew?

Why isn’t this course being used anymore?

Did you notice that I mentioned the answer book? Answer book. Answer book. Answer book. That makes me wonder something.

Yes, each volume had answer books and teachers’ guides:

Using Latin 1 Guidebook,

Using Latin 1 Translation Key,

Using Latin: Answer Key to Tests and Practice for Book One,

Attainment Tests for Using Latin Book One,

Using Latin 2 Guidebook

(earlier edition here),

Using Latin 2 Text Edition,

Using Latin: Tests for Book Two,

Attainment Tests for Using Latin II,

Using Latin 2 Translation Key,

Exercises in Writing Latin for Using Latin III,

Tests and Practice for Using Latin III, and

Guidebook and Translation Key for Using Latin III.

Isn’t this ridiculous? Why on earth would this rubbish be needed? If the teacher knew the language, the teacher would not need cheat books.

So apparently the authors of Using Latin understood from the outset that their exceptional text

would be in the hands of incompetent teachers who were unable to speak a sentence of the language.

Now, let’s think this through.

When your mommy took a few steps in front of you and said, “I’m walking,”

and then when she held up your hands and helped you take a few steps and said, “You’re walking,”

and then when she took a few steps along with you, saying, “We’re walking!”

you began to learn English.

Now, suppose your mommy hadn’t done that.

Suppose, instead, that your mommy had taken a few steps and said,

“First-person singular present gerund of the regular intransitive ‘walk,’ ”

and then held your hands up and helped you take a few steps with the explanation,

“Formal second-person singular present gerund of the regular intransitive ‘walk,’ ”

and then walked with you to say,

“First-person plural present gerund of the regular intransitive ‘walk,’ ”

you would have burst into tears and to this day you would never have learned a word of English.

Evening: “Tell your daddy what we did today!” Silence.

Mommy gets worried and nervously prods you along:

“First-person singular and plural and formal second-person singular present gerund of the regular verb ‘walk.’

Don’t you remember, dear?”

Daddy would not have been pleased. Why couldn’t his child answer right away?

Yes, that’s how we were taught Latin.

“Pop quiz: Write an active-voice sentence using a second-declension masculine-singular nominative

with past participle and plural third-declension neuter genitive

with a third-conjugation third-person-plural pluperfect main verb

and a perfect-tense third-person-singular intransitive fourth-conjugation auxiliary verb with plural feminine accusative in the third declension

and neuter dative and masculine ablative both second declension, and be sure to emphasize the locative, while ending with a subjunctive phrase.

Geraldine, what’s taking you so long?

If you can’t follow such simple instructions, why don’t you drop and take an F and switch to some Mickey-Mouse class

like basket-weaving or something?”

(I’m exaggerating a bit, but not much.)

The only way to learn. Yet we all got passing marks.

Despite my passing marks, the class wore me down, defeated me, made me feel like a total idiot, an abject failure.

It also made me much more hostile, much more of a nasty cynic than I had ever been before.

If memory serves, I got straight B’s.

Remember when you learned arithmetic?

You didn’t spend one night staring at an addition table and at a multiplication table to master the topic.

It took a lot of practice, didn’t it?

It took hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of hours of practice for seven or eight years, didn’t it?

After you were done, you never thought again about an addition table or a multiplication table, did you?

You just know how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide, right? You see 8×7 and you know that means 56, yes?

You don’t need to think of the table anymore, do you?

Similarly with languages.

Languages are more than tables and charts and rules.

Without conversation and/or immersion, you can’t learn a language.

There is no conversation or immersion in any school that I know of, at least not in this country.

(Well, there is, but only at the FSI, and admittance is restricted to diplomats.)

Right at the beginning of Using Latin, Book One is a story about Roman aqueducts, all of six lines,

and that is followed, in the next lesson, by a story about American aqueducts, all of six lines.

My memory, which I’m quite sure is accurate, is that we spent several days on those twelve lines, and that we performed horribly.

A good teacher, instructing by conversation, would get through those two little stories in 30 minutes or less.

A good teacher, instructing by conversation, would happily get her students fluently to the end of the first volume before the end of the first semester,

and there would be no confusion at all.

We did not have a good teacher, yet we got passing marks, because we could recite the noun endings and the verb endings.

Unfortunately, my memory of high-school Latin class is incomplete.

Our teacher was a nice gal, I admit, but she had not a clue about how to teach her subject.

The ebullience she displayed on the first day of class steadily declined over the months, as she became ever-more exasperated with us hopeless students.

She was quite young, and I wouldn’t be surprised if this was her first time teaching.

During the first year, she drilled us mercilessly on word endings and grammatical terms.

When she saw that not a single one of us could understand a sentence, she did not alter her teaching method to accommodate us.

Eventually she would offer translations from the answer book,

and we would see that, yes, the translations seemed to make sense, but we could never understand why, and we could never do such a translation on our own.

If she were to have graded us fairly, she would have awarded each of us a zero percent.

That would not have pleased the school board, though, and so she passed us all with A’s, B’s, and C’s.

Now, if a teacher sees that not a single student can understand a single sentence, then that teacher should begin to question her teaching method.

She did not. She assumed the students were at fault, not she.

She did no soul searching. She asked nobody for advice. She just kept drilling us on word endings and grammatical terms.

When we failed to understand a sentence, she would drill us more on word endings and grammatical terms and assign us written homework to drill even more.

So, we never dwelled on any of the book’s stories.

We never understood one. Not one. Not a single one.

As the first year dragged on, she told us to bunch up our desks and work in duos or trios.

We did. It helped not a bit.

In the second year, she operated out of a different classroom, one that had tables in place of student desks.

We worked in groups of three or four or five or six.

As we struggled, the teacher just sat at her teacher’s desk, doing paperwork that seemed unrelated to class,

and simply left us to sink on our own and drown.

By the last semester, nobody was putting any further love into the class.

It was with resignation that we sat ourselves down at our tables, knowing that there was no way out of this mess,

that there was no way to make head nor tail of the readings,

that our brains were far too small to memorize all the paradigm charts,

that when we saw, for instance, tēlæ,

we could not figure out whether it was nominative plural or genitive singular or dative singular maybe something else altogether.

Only the context would tell us,

but the problem with context was that we had the exact same problem with every other noun and verb and adjective and adverb and gerund and participle in the sentence.

So, we sat together in our groups, pens and notepads in hand,

discussing with no enthusiasm about how to piece the jigsaw together,

looking up every chart to see which endings matched, waiting in agony for the bell to signal the end of class.

When after twenty minutes we figured out how to decrypt a sentence in a way that kind of made some vague sort of sense,

we would give up on it and move to the next sentence, which completely mismatched the previous sentence.

We no longer cared.

We would perform the same surgery on the next sentence, and then discover that the third sentence was another mismatch.

Oh well, we knew we could never get anything right, but we knew also that no matter how goofy our mistranslations were,

we had enough excuses to provide the teacher that she would pass us anyway.

I remember a high-school chum showed me a page from National Lampoon.

He thought I’d be amused.

Which issue? I don’t know.

Which year? Sometime between 1974 and 1981, I guess, though probably 1977 or 1978.

It was a little one-page photo-novel that showed us two guys in cheap imitation togas, and it opened with the guy on the left speaking to the camera:

“Do you remember how hard Latin was in school? Well, it was no easier for us Romans.”

The guy on the right says something in Latin, and the guy on the left asks what that means.

“I don’t know.”

Then the guy on the left says something in Latin to the guy on the right.

“What did you say?”

“I haven’t got the foggiest idea.”

The guy on the left turns to the camera again: “See what I mean?”

It was too true. Too true.

As I now leaf through this Using Latin book, I discover to my surprise that, after page 55, there is not a single story I remember, not even vaguely.

It is as though I am seeing these stories for the first time.

I remember only the tables and the grammatical terms, on which we were so abusively tested.

So, I’m curious, and I’m looking through Using Latin, Book One,

while searching the cobwebbed corners of my memory, to see if I can recognize where we left off.

I think that by the end of the second year we were midway through Lesson LXX, page 354.

Two years. Two years. Two years to get to page 354 of a book that, I can now see, is incredibly easy.

I think the ablative absolute (page 348) was the last formula we were told to memorize,

and because the year was grinding to an end, not one of us bothered to memorize that formula.

In looking at this passage again, I see that what it presents is not even a formula.

There’s nothing to it at all.

I don’t even know why students need to learn the term “ablative absolute,”

since anybody can understand it and speak it without any explanation,

without knowing that linguists take an interest in this entirely unremarkable, entirely self-evident sentence structure.

The meaning is obvious without explanation, and anybody encountering it a few times would unconsciously begin to adopt it.

What’s the big deal? Sheesh.

Then we all just sleepwalked through the opening of Lesson LXX, and we were done, not caring any further,

all of us knowing we would get our passing marks and then be done with this rot forever.

By the end of the second year, spring 1977, my impression was that the teacher was nearly as relieved as the rest of us that the agony was drawing to a close.

By the next semester, autumn 1977, she was gone.

Had she resigned? Had she transferred? Had she been canned? I never learned.

Here’s what’s so crazy:

Suppose that, without ever having enrolled in Latin class, I had found Using Latin at the nearby Goodwill second-hand shop for twenty-five cents.

What would I have done? Simple: I would have begged my parents for twenty-five cents,

and then I would have walked back to the Goodwill and purchased the course and whizzed through it without a problem.

I would simply have treated it as anything else I studied on my own:

I would have spent a winter vacation or a summer vacation on it, I would have lost myself in it, and I would have reviewed, reviewed, reviewed.

It would have been so easy.

I never once treated class work the way I treated self-study, unfortunately,

simply because, during a school year, there was never a moment in which to do so.

That was my scholastic doom — and not only mine.

Since the teacher was teaching, I let her do the teaching.

I was convinced that a professional would be better at teaching me than I would be at teaching myself.

When the class proved impossible, I was certain that I was at fault.

It never occurred to me to try a different method.

I simply thought the topic was beyond my ability.

I was determined to try it again, though, after maturing a little bit.

In my decades on this planet, I have discovered that what I perceive is not what others perceive,

that my conclusions differ entirely from other people’s conclusions.

When I speak, others misunderstand what I say.

When others speak, I am continually caught off-guard and do not know how to respond adequately.

There is nothing to be done about this.

A year or so after having completed those two torturous years of high-school Latin, I bumped into a fellow alumnus at the Coronado Shopping Center.

We chatted for a while, and I began to remark how odd and how preposterous and how criminal it was that, after two years of torment in Latin class,

neither of us could speak, read, write, or understand a single sentence.

I began to make that remark, but I did not finish.

You see, as foreigners cannot help but notice, with the blessed exception of the American Indians, US citizens do not converse. Not at all.

Instead of conversing, US citizens aggressively cut one another off in mid-sentence.

Apparently, US citizens consider that to allow the other person to complete a thought is to concede defeat, and US citizens hate to be defeated.

So, before I could get more than three or four words out, my fellow alumnus cut me off at the utterance of the word “Latin.”

He blurted out that, now that he had mastered Latin, he was planning to conquer a different language (I cannot remember which one).

I was dumbfounded.

Mastered? Mastered? What had we mastered?

That was my first encounter with the idea that students are convinced that they have “mastered” a discipline

by simple virtue of having attended class and gotten a passing mark.

Skill is not the issue, as far as they are concerned.

Only the mark on the report card counts for anything.

Thus, a good mark in Latin means mastery of Latin, even though the student cannot understand, speak, read, or write a single sentence of the language.

I find this nightmarish, worse than surreal.

Few would agree with me.

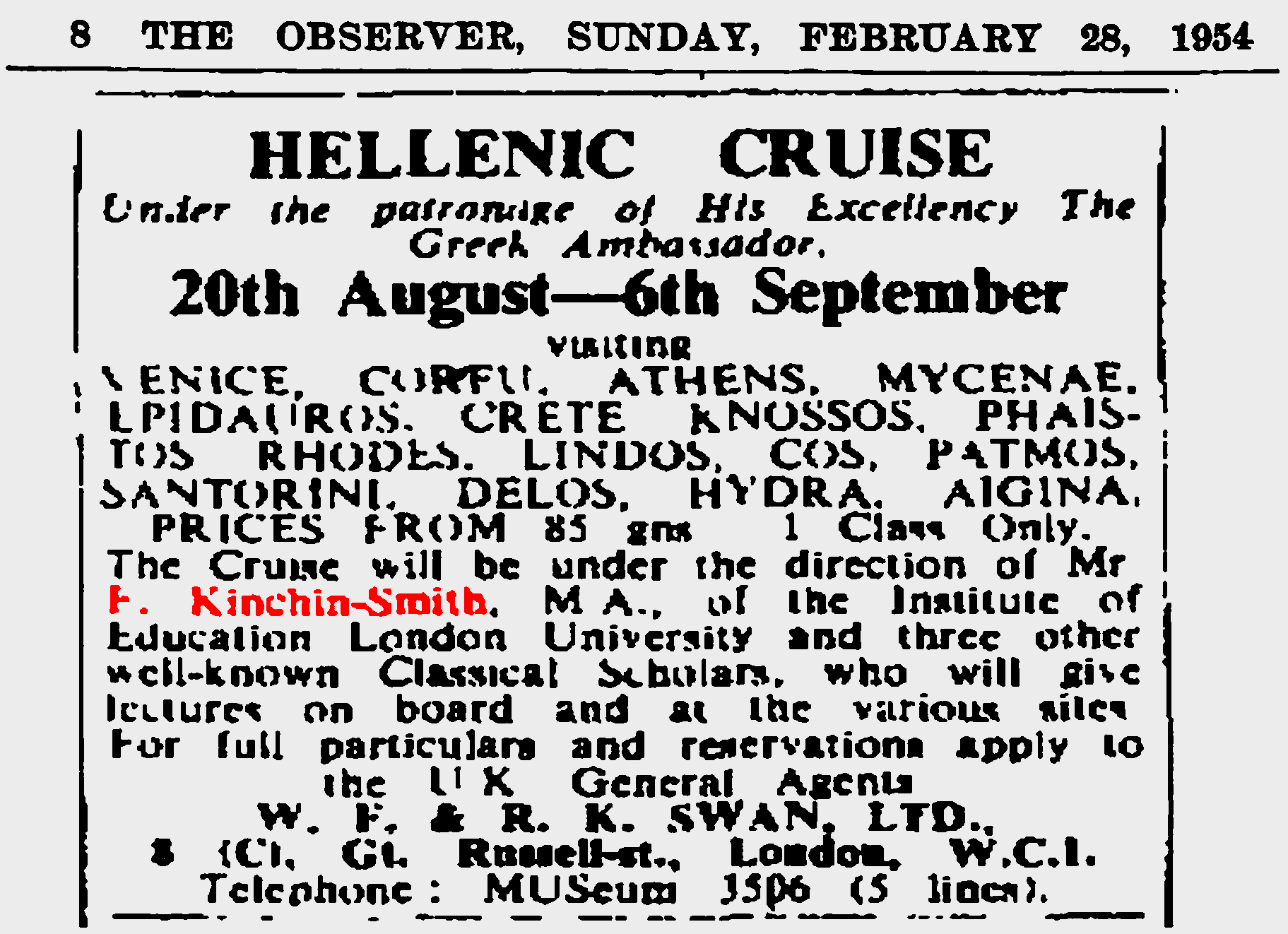

At about the same time I started Latin class, I deviously picked up a little bit of Greek, too, courtesy of Sofroniou’s little

Teach Yourself book and the

Cortina book with its accompanying 12" vinyl records

(I think the set included ten records, which seem not to be available anywhere anymore for any price — I should dig mine out of storage —

oh, wait, the entire set was just posted at Yojik),

and when I could finally understand some of what my grandmother and great-grandmother were saying behind my back,

I discerned at once the real reason why they had not wanted me to learn Greek.

(Life Lesson Number Two: Genuinely sweet people never make a show of being sweet.

People who make a show of being sweet are putting on an act. Beware.)

Other members of my family did not speak a single word of Greek and had no interest in learning.

My father grew up speaking Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu, and the RAF taught him some French and German.

(How do I know this?

I know this only because my seventh-grade English teacher at Cleveland JHS was John Duran, who reminded me so much of

Mitch Miller.

Mr. Duran asked my father to address class one day for a couple of minutes,

and this is what my father told everybody. It was all news to me.

In those few minutes I heard nearly all I ever learned about his earlier life.

He was an extremely uncomfortable public speaker, by the way.)

Only once did I hear him speak one of those languages.

We were in a car with one of his acquaintances from the old country, and the conversation was in English.

Then, for just a few seconds, when he said something that he didn’t want me to understand, he switched to one of his native languages.

Then it was right back to English.

Never again did he speak so much as a syllable of any of these languages in my presence. “We’re AMERICANS now!!!”

He was disgusted beyond words when I showed interest in Greek.

Now, when I discovered, around age 16 or thereabouts, that Classical Greek and Modern Greek were different animals,

my Greek grandmother and great-grandmother blew a million gaskets.

They were screaming that I was telling lies, lies, lies — lies for which god would never offer forgiveness.

They insisted that Greek had never changed since god established it at the beginning of the universe

a few thousand years ago as the original and only true human language.

Because Greek was established by god as the only true human language, it could not possibly change — ever.

To suggest otherwise was a sin, a sin so vile that not even confession on Sunday would absolve it.

As for my statement that the pronunciation had changed over the past three thousand years,

that, too, was an unutterable offense against god and all his creation.

Any attempt at reconstructing an earlier pronunciation was offensive, worse than offensive,

it was an outrage that put me at grave risk of spending all eternity in the fires of hell.

They were convinced that

the current pronunciation was the original pronunciation.

It was anathema, apostasy, heresy, blasphemy to say otherwise.

Realizing that she was on the verge of cardiac arrest, my great-grandmother tried to psych herself into relaxing,

and then, forcing on a smile, she recited a prayer in the Modern Greek pronunciation,

which proved, to her satisfaction, that Greek had never changed.

Irrefutable logic.

Of course, anything can be mispronounced, which is an argument my familial Greeks would never have understood.

Also, never mind that the prayer, from Byzantine times, had from its beginning been in pretty much the Modern Greek pronunciation,

because it was essentially Modern Greek.

After that lengthy scene, unwitnessed by any other family members, I learned that it was best to keep my mouth shut.

I discovered, at age 21, that this was the common perception among Greeks —

not all Greeks, of course, but certainly the Greeks who were known to my family.

My great-grandmother , normally devoid of any form of curiosity,

decided that she wanted to learn a little bit about Spanish.

That was, I think, in 1980.

She asked if I could go to the library and get her a book, any book, in a parallel Greek/Spanish translation.

No problem.

I checked out a volume of Plato’s dialogues, and she could not make head nor tail of them, but would not admit to such.

She just quietly gave it back and said that the Spanish was too advanced for her.

I was expecting the standard excuse that there were better things to do than to look at the works of a heathen,

but she did not make that excuse, I assume because she had no clue who Plato was.

I doubt her education extended beyond age eleven, and by age twelve she was assisting at a military hospital when the First Balkan War was declared.

She was shattered by what she witnessed, with skulls blasted off revealing brains.

I wanted to hear stories, but she did not know how to tell stories.

That was the only detail she revealed.

Then she had a shotgun marriage at age fourteen.

She never said that it was a shotgun marriage,

but the details she inadvertently let slip left room for no other interpretation.

My grandmother and great-grandmother blew even more gaskets and went on screaming rampages

when I pointed out that they were mispronouncing the word “Byzantine.”

I knew to keep my mouth shut, sealed shut with glue, but I nonetheless made the dumb mistake of saying something.

They pronounced the word as “Bison Teen,” and went through the roof with blood-curdling shrieks that “Bison Teen”

was correct.

“It’s Bison Teen, Bison Teen, Bison Teen!!!!!!” came the deafening screeches.

My offer to open the dictionary was rebuffed, for the dictionary was certainly wrong, because the Greek was

“Βυζαντινός,”

“which means it’s Bison Teen, Bison Teen, Bison Teen!!!!!!”

Again, that was irrefutable logic.

After all that, why did I later point out that their pronunciation of epistle, EH-pist-əl , was incorrect, and should be, instead,

e-PIS-əl.

Screams, shrieks, endlessly.

Grandmother: “In Greek it’s ἐπιστολή,

and so it’s EH-pist-əl , EH-pist-əl , EH-pist-əl!!!!! ”

Realizing, again, that her dangerously enlarged heart was about to give out, my great-grandmother tried to calm herself down,

and then made a joke, forming her fingers into a hand gun, saying that my pronunciation was a mistake for “a pistol.”

I never made a comment to them again, about anything, unless it was false flattery to calm their rattled nerves.

When they later asked for my opinions, I just said whatever would make them happy,

and tried not to cringe at their defiant looks of smug satisfaction.

My grandmother had a fourth-grade education, which convinced her that she was smarter than any other lay person,

and which also put her, I think, a year ahead of my father, who was similarly convinced that he was smarter than almost anybody else.

I went to the university. I didn’t want to, but my father’s word was law, and he was paying out of his meager funds.

Meager the funds were, and meager was tuition: about $400 per semester and a further $400 per semester for textbooks.

(Nowadays the price has gone up ten-fold.)

This was about the last thing in the world I wanted.

I so much wanted to get a job and move out on my own.

Surprisingly,

I had gotten a job while still in high school: minimum wage and fired within four months.

This was Albuquerque: If you were a CPA or a nuclear physicist, the gates would swing open wide.

If you were anything else, good luck.

Maybe after a year of searching you could land a job as a janitor or busboy and then be fired without pay after two days.

New Mexico was the third-poorest state in the union, so what do you expect?

(Things have improved, though. Now it’s the sixth-poorest,

with the second-highest poverty rate and third-highest unemployment rate.)

Since I couldn’t find employment anywhere, I continued to live at home where I was at my father’s mercy.

He had no mercy. So, I went to the university.

I soon came to a conclusion that I never had the courage to utter aloud until just these past few weeks: Higher education is a scam.

“Racket” might be a more appropriate word.

There are rituals, but there is no learning, or almost none.

Higher education, just as lower education, is designed not to enlighten us,

but to turn us all into automata, and to give the illusion of learning.

As for the frequent complaint from the far right that universities are bastions of liberal propaganda, my response is simple:

That complaint was invented by people who had never sat in on so much as a minute of a university class.

Universities are bastions not of liberalism, but of suppression and stultification.

Universities do not indoctrinate liberal ideology; they indoctrinate apathy.

It’s all a fraud — kindergarten through graduate school, it’s all a fraud.

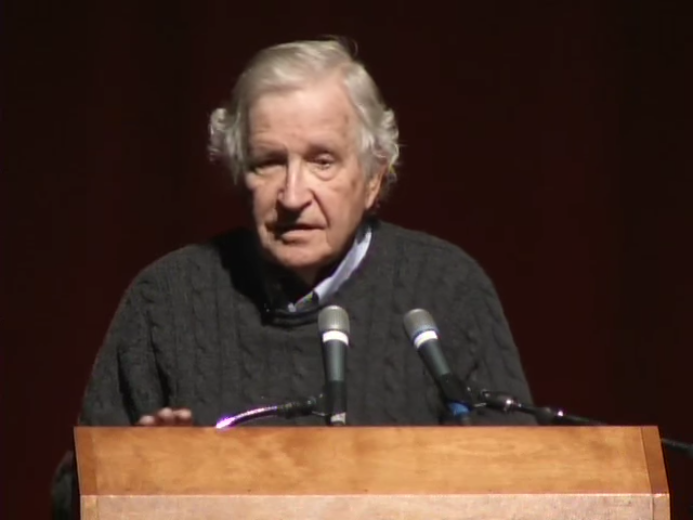

“Education: For Whom and for What?”

This was an invited lecture presented, ironically, at the University of Arizona.

I enrolled in Latin 101, hoping that this time it would be better and that I would finally master the language.

I was slightly older, slightly less immature, and determined never to give up on anything.

Since we were required to take four semesters of a foreign language, I took four semesters.

Text: Frederic M. Wheelock, Latin: An Introductory Course Based on Ancient Authors (Harper & Row, 1971),

supplemented, of course, by the professors’ own ideas and mimeographs.

There it was again: chart after chart after chart after chart after chart after chart

of noun endings and verb endings and the technical names of each,

along with rules, rules, rules, rules, rules, rules, rules, rules, rules,

followed by maybe 50 words of vocabulary for memorization,

then ten practice sentences, and finally a fill-in-the-bank quiz and a three-line translation exercise.

No conversation. No spoken Latin. None. Ever. Never never never never never never never never never.

Next lesson: charts and charts and charts and charts and charts

and rules and rules and rules and rules and rules,

50 words of vocabulary, ten practice sentences, a brief fill-in-the-blank quiz and a three-line translation exercise.

Then the professor (whose name I cannot remember) would hand out mimeographed sheets, saying,

“Now for some real Latin.

Your homework tonight is to translate this poem by Vergil.”

Nobody was learning anything. Most students dropped out. I couldn’t blame them.

Now, in all fairness I should confess that I was a moron.

I tried to look at the bright side, and, since Wheelock’s sample sentences were

not silly new readings about aqueducts or the ant and the grasshopper, but were instead all taken directly from Roman authors,

at the beginning of the course I said I was impressed,

and I really really really really tried to make myself believe I was impressed.

I was a moron.

Out of curiosity I just ordered a used copy of Wheelock’s 1971 edition.

I see now that my description above is not quite accurate, but who cares? The gist is correct.

Dreadful book. One of the worst books ever written.

Impossible to learn anything from it, except how to write a truly awful book.

Worse than philosophy books.

Worse than sacred religious books.

Worse than Krishnamurti.

Worse than von Däniken.

Not as bad as The Courage to Heal.

Worse than

Finnegans Wake and, if anything, even less comprehensible.

|

Suppose you want to make sure that,

no matter how many years you put into studying Latin, you’ll never be able to really “read” a sentence.

Is there a recipe for disaster here?

There is.

Here’s how to do it:

(1) begin studying from Wheelock’s Latin: An Introductory Course Based on Ancient Authors,

(2) following the book, learn little snippets of Latin grammar, always moving around among categories so that you’re thoroughly confused —

e.g., study a couple of verb forms the first week, then learn a noun declension, then learn a different verb tense, then move to adjectives — and

(3) make sure that your reading consists of short sentences taken from Latin authors about how the Romans hated money.

This way, you can make sure that you’ll never be able to read Latin even if you study it for forty years.

It passes the time.

|

And that, in a nutshell, is how we were all taught Latin in school.

You probably think I’m exaggerating about how badly languages are taught in school.

Well, read Daniel R. Streett’s

“The Man Behind the Curtain — or, The Dirty Truth about Most New Testament Greek Classes (Basics of Greek Pedagogy, pt. 2),”

καὶ τὰ λοιπά, September 10, 2011.

As you can see, I’m not the only one griping.

That’s about the most damning indictment of higher education that I’ve ever encountered, and it is true, completely true.

So, my grouchiness has good company.

Appropriately, The Life of Brian premièred at about this time.

Nice movie. Clever movie. Not a great movie, but a nice movie.

It had some good points to make about the authoritarian mindset and about the disordered desperation of the followers of Falwell and Bakker and their ilk.

It had one of the most tragically heartbreaking scenes in all cinema history (the hermit, if you’ll recall).

Overall, it was an extremely sad movie, but it did have some really good laughs (my personal favorites being the

rooster and

the space battle),

though one of the funniest moments hardly got a reaction:

It was a fairly large house that opening night, all things considered.

There were maybe 200 or so people in the auditorium of the Fox Winrock Twin Screen 1

(pitilessly carved out of the once-glorious Fox Cinerama).

By 1979 it was rare for an auditorium to get so many as 200 people at a time.

The audience, without exception, enjoyed the movie, and the laughter was frequent.

The above scene, though, got almost no response.

There were a couple of forced chuckles, here and there, which came at the wrong moments.

Apparently, most of the people in the audience had never been tortured by Latin instructors.

But... apparently a few had.

It was so easy to spot them.

I remember in the third semester we had a substitute professor one day when our regular instructor called in sick.

I can’t remember his name either.

He had us painfully translate some authentic Latin jokes, which he had recently discovered,

and he told us how shocked he had been by this discovery.

He had never before realized that the ancient Romans had had a sense of humor.

This, for him, was a revelation.

I listened in disbelief.

This was a professor? A professor, a Ph.D., who had passed his oral exams and had been admitted to teach at a university,

who didn’t comprehend that people 2,000 years ago could joke around and laugh??????

I didn’t even know how to react. I remember that my mouth was agape.

What did this guy grow up believing? Did he grow up believing that laughter was a US invention first patented in 1950?

It was in our third semester — no, not the third, the fourth semester — that our instructor chose not to instruct one day.

Instead she walked us a few buildings over to be the guests at a class in Roman history.

Out of discretion, I shan’t mention the historian’s name, except to say that I had never been at all impressed by him.

When class let out, I walked out with my instructor by my side, as she chatted with the historian.

He was quite intimidated to be speaking with a Latin instructor.

I can’t remember his verbatim comment, but I have no doubt that my paraphrase is nearly verbatim:

“Any other language, you just study it for six months and you’re speaking it.

But Latin, no. You study it for eight years and you still can’t read it!”

My instructor did not disagree.

By the fourth semester I was one of only four remaining students.

No. What am I saying? I’m misremembering. I was one of only three remaining students.

Lester gave up after the third semester.

With such a small population, there was no need to meet in a classroom.

We met instead in the instructor’s office. (I refuse to provide her full name.)

Our instructor grew excited when she discovered a passage of prose she had never seen before.

“Let’s translate this together!” she exclaimed.

She examined the first sentence for maybe ten or fifteen seconds,

trying with difficulty to figure out where the verb was.

“Maybe this is the main verb. Let’s see.”

Then she got lost and started looking up words in the Latin-to-English dictionary.

She tried the sentence again and again, “No, that’s not it.

That’s probably the verb in the subordinate clause.

So, this is probably the main verb.”

She tried it again, “Yes, that’s it. This is the main verb.

Okay. Let’s see. Hmmmmmm. That ablative must mean something else.

Let’s see what else it might mean.”

She looked it up in the dictionary. Maybe five possible definitions.

She tried them one by one until she found something that seemed to work.

This went on and on and on.

At the end of the hour, as we left her office and walked down the hall,

I asked her, “Diana, can you speak Latin?”

“Of course not! Nobody can!”

She said that happily, with a wide smile on her face.

“Can you think in Latin?”

“Of course not! Nobody can!”

“Can you read Latin without translating?”

“Of course not! Nobody can!”

That’s when I finally understood why I could never understand.

Never before had the light bulb come on. Never before had it clicked.

So, it wasn’t me after all!

It wasn’t my fault!

I wasn’t stupid! I was being taught by someone who didn’t know her topic.

I thought back and realized that none of my Latin professors and teachers was qualified to teach,

since not one of them could speak the language.

That’s why there was never any Latin conversation — not one line of Latin conversation. Ever.

That explained the historian, who specialized in Classical Rome, who also could not read, write, or speak Latin.

Why were these people teaching?

Why did they think they were qualified to teach?

Why were they allowed to teach?

As for Wheelock’s book, we never finished it.

This was just like high school:

two years and we never finished it.

It was too difficult for the students.

It was too difficult for the instructors.

So, we never finished it.

Hmmmmmm. Where did we leave off?

I leaf through the pages, and to my surprise I discover that we struggled through all 40 chapters,

but we barely touched the readings and exercises that filled the second half of the book.

Two years, four semesters, to suffer through a mere 195 pages.

This is what higher education is all about, yes?

How did the other college kids manage the language requirement?

I watched. I observed. I learned.