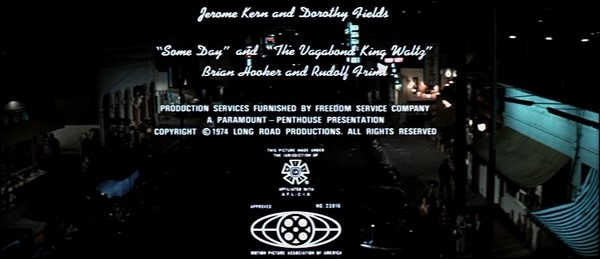

Notice the production names: Girard, Sherman, Centennial, MGM.

Not a peep about Guccione or Penthouse.

That’s because there was nothing to peep about.

In a syndicated article by Earl Wilson,

which I found printed as

“Culp Takes a Cold Swim,” in

The Bucks County [Levittown PA] Courier Times, Monday, 3 November 1970, p 23, we read:

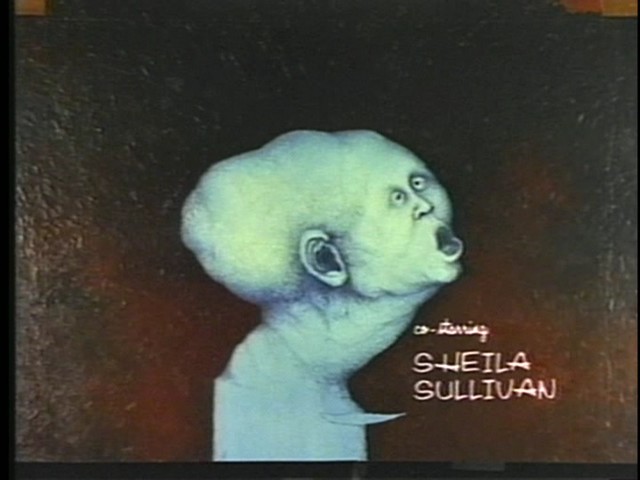

Robert Culp sprang gallantly to his feet,

bowed, and kissed the fingertips of his blonde actress girl friend

Sheila Sullivan....

“This girl is out of this world!” he’d said saying before she

arrived to have coffee with us at the Ground Floor. “It’s like

seeing Carole Lombard come back to life. She’s sensational and

it’s her first movie. How old

is she? I don’t know... she’s

30 on up... she’s no kid.”

Culp, getting divorced from

France Nuyen, was exclaiming

about a picture he did with

Sheila and Samantha Eggar in

Canada called “In The Beginning.”

Sheila, whom he’d been

dating before the picture started,

had some memorable scenes

with him — once they had to

get “parboiled” for a nude swim.

“We did the scene the hard

way,” Culp dourly confessed.

“It was so cold — well, Don

Franks, one of the cast members,

built us a little Indian

sweat lodge with hides and little

reeds — and hot rocks in the

ground like a sauna — and we

stayed in there and parboiled

ourselves so we wouldn’t feel

the cold when we went in the

water.”

Sheila spoke up. “You don’t

feel the cold for about 5 minutes.

We had to do the scene

five or six times. By the end

of it, I couldn’t feel my teeth.

I felt like I was novocained all over.”

“It was supposed to be summer

and supposed to be an idyllic

swim — boy, could we act!”

Culp said.

“I wouldn’t do that for George

Stevens or John Ford — I

wouldn’t do it for anybody...

this,” he said, “is the kind of

picture you wait for all your life.”

They shot it around a famous

old inn in Vancouver. “It was

built around 1910, allegedly as

a summer place for Kaiser Wilhelm

after he won the first

World War — but there was a

hitch in those plans,” Culp smiled.

“There are only 3 things I

ever did professionally that I

liked — everything else you do

just for the money, you get in

and get out...

“One was ‘I Spy,’ way back in

’64. Nobody had ever seen a

white person and black person

in a continuing basis on TV before...

then ‘Bob and Carol

and Ted and Alice’ — and then this...”

“How about Sheila?”

“She’ll have billing... I

don’t think ‘Introducing Sheila

Sullivan’... that’s too corny...

“We spent 4 months living

in a trailer in the woods in

Canada. Will we get married?

Well, we haven’t run it down

that far. I really don’t know yet.”

The picture, he said, is about

an architect who builds buildings

he hates. His wife loves

the Portofino set and all the

false values he hates; he tries

to break away and goes a little mad.

“The story is that I decided

to do it because I couldn’t understand

it,” Culp said. “It’s

true, I didn’t understand it.

But that was because there

were 3 pages of the climax missing!” |

Then nothing happened.

Why? Well, take a look at the Hollywood Reporter, Friday, 6 August 1971:

Stone Prods. sues

‘Grove’ producers

for $1.2 million

Stone Productions Inc. and Samantha

Inc. filed suit Tuesday in Superior

Court against Centennial Production

Co. Inc. Mercantile Financial

Corp., Filmhouse Ltd., and Consolidated

Film Industry for $1,218,750

damages for deferred compensation in

connection with an agreement to furnish

the services of Robert Culp and

Samantha Eggar in the film, “The

Grove.”

Stone, which claims it furnished the

services of the players, is asking for

an injunction to prevent the defendants

from using the film negative

and for a declaration of rights under

an agreement made in May, 1970.

Stone claims it was guaranteed payments

aggregating $175,000 plus

profit shares. The suit alleges breach

of contract. |

That sounds to me like what business folks call “undercapitalization.”

C. Robert Jennings, in “‘Slug-Like Vancouver’ — Filmland on the Fraser?,”

Winnipeg Free Press, Wednesday, 24 November 1971, p 22, interviewed the

screenwriter/director:

Barney Girard, who made

the still-unseen picture, The

Grove (now sadly in bankruptcy),

with Robert Culp and

Samantha Eggar, says his

crew costs were half what

they would have been in Hollywood,

that “even if we had

worked Saturdays and Sundays

and were a week slower,

I could save a hundred grand.” |

Now that is fascinating.

The movie was “still-unseen” and Centennial Productions had filed for bankruptcy.

With that background, there is no doubt about what happened next.

Stone et al won the suit and acquired the film, which it would sell off at cost just to get rid of it.

So in 1972 Guccione launched a separate corporation,

Penthouse Pictures, Inc., to isolate/insulate his other organizations,

and had the new corporation purchase all rights from Stone et al.

With copyright ownership, he was free to have his employees

make the film more commercial.

There is no telling what condition the movie was in when Penthouse Pictures acquired it.

It may or may not have still been the authentic version.

It may well have been tampered with by Stone et al or some emissary thereof.

But it is unquestionable that Penthouse commissioned a firm to film something new,

and it was actually quite beautiful to look at:

a psychedelic multiple exposure of a topless dancer,

as well as a dancer in a skeleton outfit,

all accompanied by an acoustic guitar.

That footage was intercut into a domestic scene,

as though it were a flashback of some sort.

But by the time the movie finishes,

we realize that it was not a flashback after all; it was merely meddling by Penthouse.

Penthouse further enhanced the film with a country singer surrounded by three nude women.

Thanks to a newspaper article, we have an approximate date

for when this happened (and we learn about yet another tentative title).

Mary Murphy, “Movie Call Sheet,”

The Los Angeles Times, 2 December 1972, p A6:

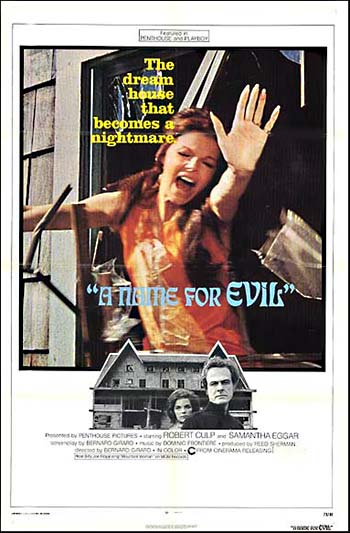

•Billy Joe Royal has

been signed to sing the title

theme for “A Time for

Evil,” a Cinerama feature

starring Robert Culp and

Samantha Eggar. The

song is “Mountain Woman.” |

Billy Joe Royal’s performance was force-fitted into the scene of the hoedown,

but the footage simply did not match, and the intercutting is rather jarring.

I wish I could see how the scene originally played.

Penthouse then hired an editor to simplify the movie, cutting it down to 74 minutes.

In this short version, characters and relationships were never developed or explored,

leaving so many loose ends that it’s no wonder people had trouble following the narrative.

I would guess that the original was far more ambiguous and a bit challenging,

and that the haunted-house story was a suggestion, planted into disordered minds, that flowered under duress.

It was surely not only the Robert Culp character who was affected, but the Eggar character too, as well as many others.

But I can’t be sure of details, for the evidence is too sparse.

Of this much am I certain, though: The horror was only a small element in what was originally a more complex story.

By the time Penthouse got through chopping away, the minimal horror was emphasized to the detriment of everything else.

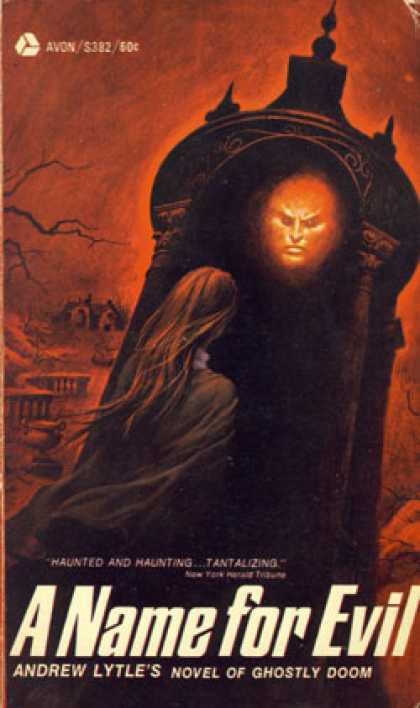

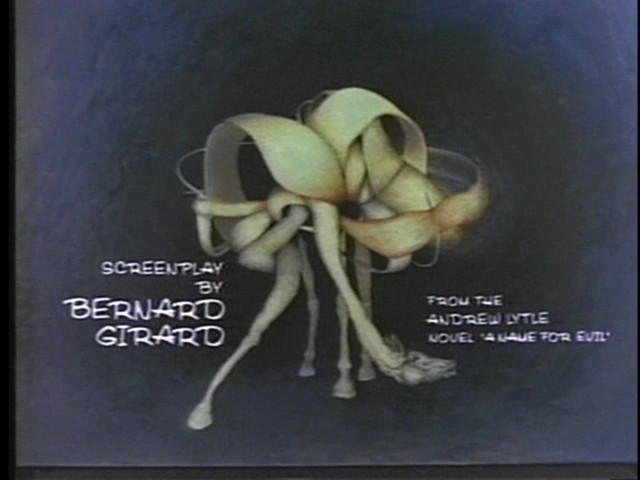

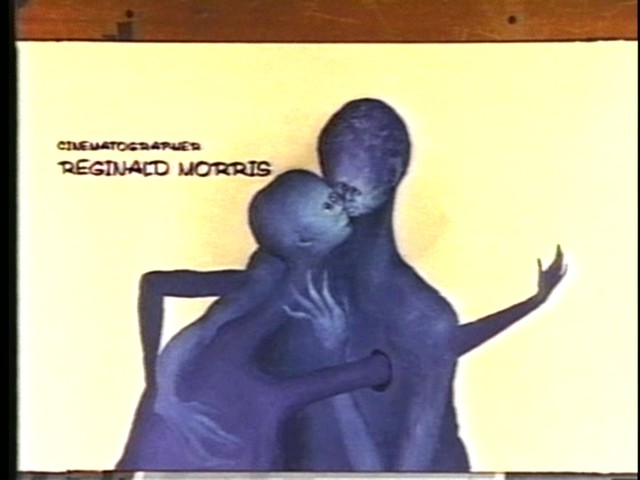

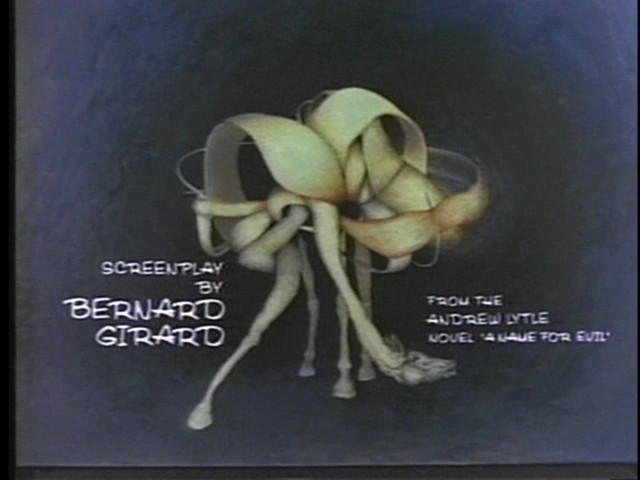

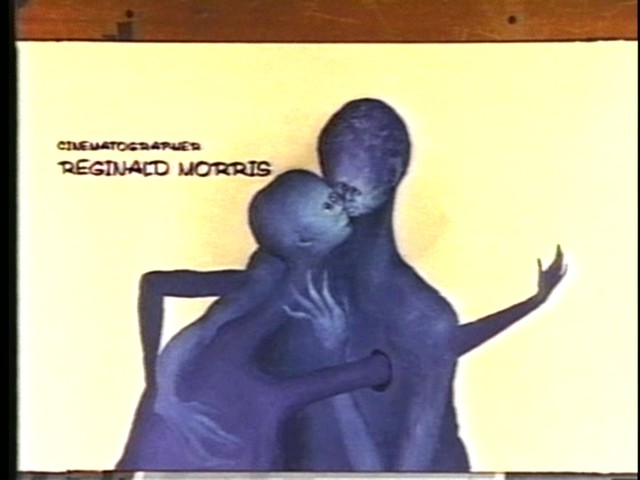

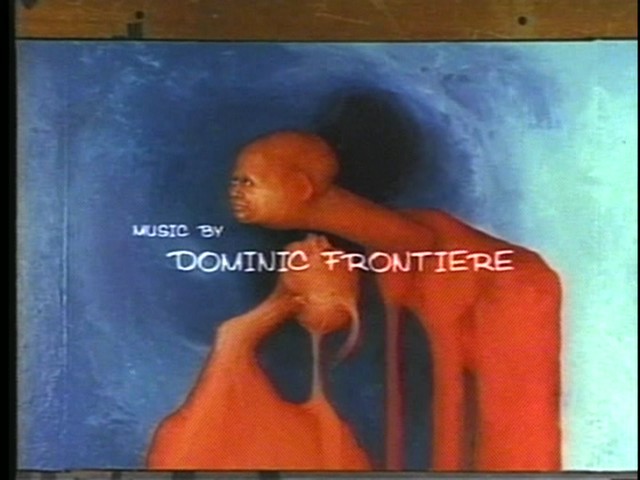

Also, I am CONVINCED that the opening and closing credits were all redone at Penthouse’s orders.

Any mention of Centennial Productions was deleted.

The clever, skillful, depressing artwork under the opening credits simply COULD NOT have been part of the original movie.

Does anyone know who did those little paintings?

On the off-chance that you’re interested in these technical details,

in an open-matte projection, such as on the DVD, we can sometimes see the table that the paintings are resting on.

The table, actually, seems to be an old-fashioned animation stand, with peg holes at the top to help with registration:

Does anyone know what the original opening credits looked like?

The soundtrack seems to have been enhanced as well.

Most of the film was shot in direct sound and was obviously — obviously —

never looped (revoiced).

And yet every now and then there actually is a bit of revoicing, and it’s painfully apparent,

especially regarding the character of The Major.

Am I right to suspect that Penthouse hired a firm to

re-record certain segments?

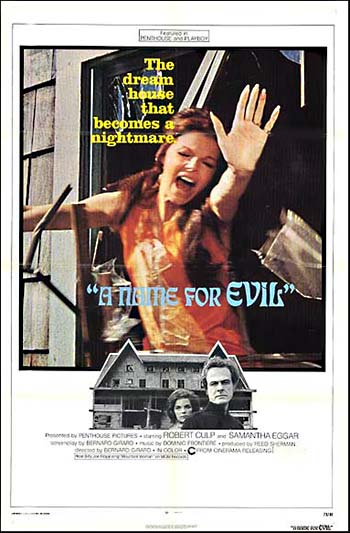

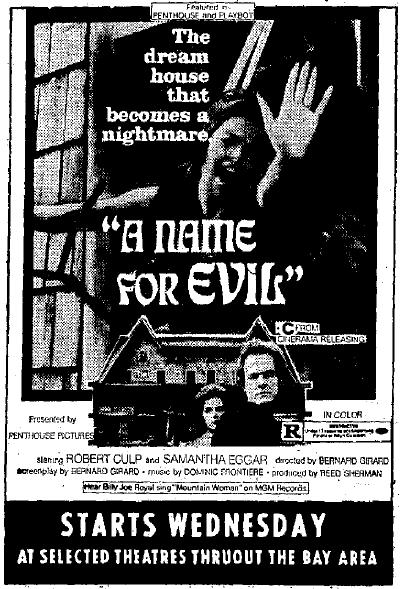

By early 1973, with one further title change, the movie was finally ready for release:

and you might also want to click here

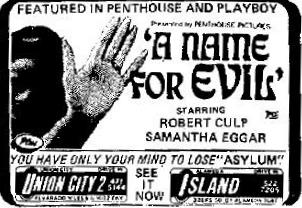

At the very top,

hard to read in this low-resolution reproduction,

is a little box that says:

...which was not true. Yes, it was featured in the March 1973 Playboy,

but it was never featured in Penthouse.

You figure it out. I give up.

Underneath it says “Presented by PENTHOUSE PICTURES.”

The poster also says that this is from Cinerama Releasing.

(I never understood how Cinerama degenerated from being a beautiful 4-strip widescreen 8-track process

to becoming a mere distributor of Grade-Z movies.)

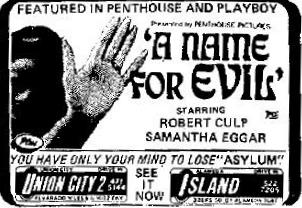

In my quick searches,

I find that the movie opened on Wednesday, 28 February 1973,

as part of a double bill with Asylum on screen 2 of the Union City Drive-In in Union City, California,

and at the Island Drive-In in Alameda, California

(it may have opened earlier elsewhere),

and that it was advertised in the Oakland Tribune

and in The Hayward Daily Review

though it was never reviewed.

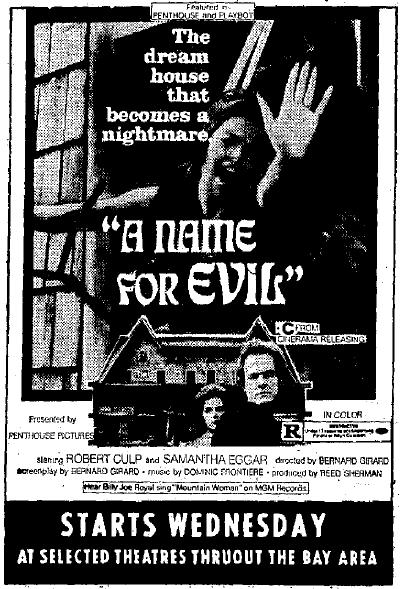

The Oakland Tribune, Sunday, 25 February 1973, p 6EN:

“Selected theatres thruout the Bay Area” is what it says. |

The Hayward Daily Review, Wednesday, 28 February 1973, p 21:

The reality was a bit different.

When it premièred as part of a double feature at two drive-ins,

its chances for recognition were crushed.

It was forever typecast as a drive-in cheapie

unworthy of review or any sort of attention. |

Other than that, all I can find are the occasional playdates here and there in smaller markets,

beginning in the spring of 1973 and meandering around the country through to the end of 1974.

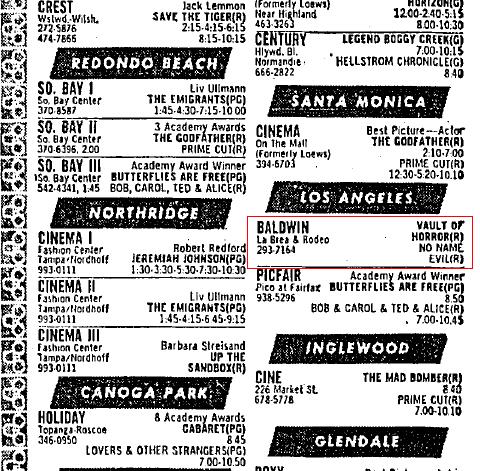

According to the application submitted by Penthouse Productions to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

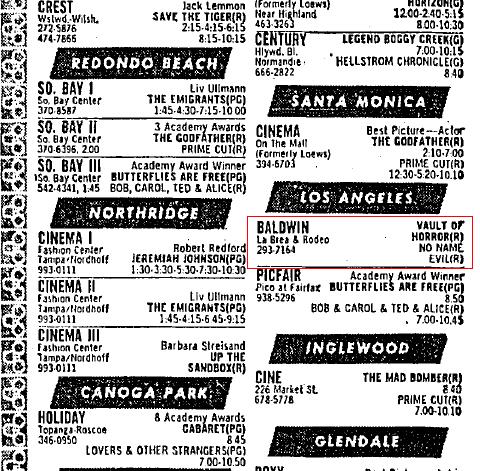

making the movie eligible for the 46th Academy Awards, the movie opened in Los Ángeles on Wednesday, 4 April 1973,

at the Baldwin Theatre,

with a running time of 85 minutes and without an MPAA rating.

The application was wrong.

It took a bit of searching to check that claim.

The running time was almost certainly 74 minutes, and the MPAA rating was R, but it did indeed play at the Baldwin,

which I would not otherwise have understood.

Here’s the eye-catching advertisement:

Penthouse, as owner, and Cinerama, as distributor, should have done a little better than that, surely!

It would be most helpful if we could find the original version of the movie

so that we could compare it with the release version.

Does the original still exist somewhere?

Or even the script would help. Does anyone know where the script is?

Oh well, maybe it’s not that important,

for while this movie does unquestionably have its virtues and some genuinely lovely moments,

it was probably never really any good,

and I’m pretty sure that even in an authentic version it would be nothing to get excited about.

Robert Culp was ecstatic about the movie as it was in production,

but I imagine he would have been disappointed had he ever seen the original cut —

and if he ever saw the release version, he probably wanted to commit hara kiri.

If I may be permitted to read between the lines,

it seems that Penthouse/Cinerama had the idea that this movie could be released to individual cinemas

and generate word-of-mouth, after which it would get bids and play the larger cities.

But apart from the magazine pictorial,

the movie was not really advertised at all, and so the strategy ended in abject failure.

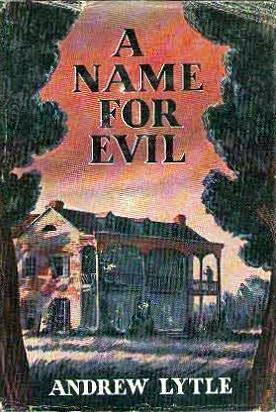

A Name for Evil was usually mentioned only in the 6-point daily list of other-movies-now-playing.

So obviously it never picked up any bids,

it never played in New York City, as far as I can tell,

and it was just dumped off onto cinemas that couldn’t find anything else to play.

And what should one expect from such a treatment?

How could such a lackadaisical promotion possibly generate any excitement at all?

People don’t see movies because they’re good,

and they don’t avoid movies that are bad.

People see the movies that the mainstream media tell them to see,

and they like the movies that the mainstream media tell them to like.

Yes, this is a social-economic experiment,

it is behavioral control, and it is mind control — and it works!!!

Penthouse tried — and tried, and tried, and tried — to buck the system,

and to get a movie to sell on its own merits.

A few movies are truly “discovered” by the public and develop a small coterie of fans solely on merit,

but I know of no movie that ever became a major success by virtue of its quality alone.

Maybe it can be done, but I don’t see how.

It certainly couldn’t be done with this movie, because there’s nothing especially likeable about it.

And when poor or nonexistent advertising makes a movie invisible,

the perception is that it must be a cheap and incompetent indie to be avoided.

Surely that’s what happened here.

I don’t know how much Penthouse paid to acquire the movie,

though I imagine it was somewhere in the area of the $1.2 million that Stone et al were seeking in damages and compensations.

For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that was the price.

For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that Penthouse got all its studio work and advertising materials and office and clerical help and 35mm prints and shipping/postage for free and had no taxes to pay.

For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that the average admission price was $1.50.

For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that the film usually played on a 35-65 policy.

For the sake of argument, let’s suppose that Penthouse and Cinerama split that 35% profit equally.

That would mean that Penthouse earned about 25 ¼ cents per ticket.

To earn back its $1.2 million investment, it would need to sell 4,571,429 tickets.

I don’t think that happened, do you?

According to word on the Internet,

there was also a TV version of this movie, with alternative footage to replace the nudity.

Was it Penthouse who prepared that? Or Cinerama? Or someone else?

Does Penthouse still even have the rights?

(Incidentally, the IMDb

also supplies yet one more alternative title: The Face of Evil,

but when or if or under what circumstances that title was actually used, I don’t know.)

After its one and only movie,

Penthouse Pictures Inc closed up shop forever, to be replaced by Penthouse Productions Ltd.

Did anyone see A Name for Evil in 1973 or 1974?

If you did see it back then,

or better yet, if you worked on the movie,

please contact me. Thanks so much!

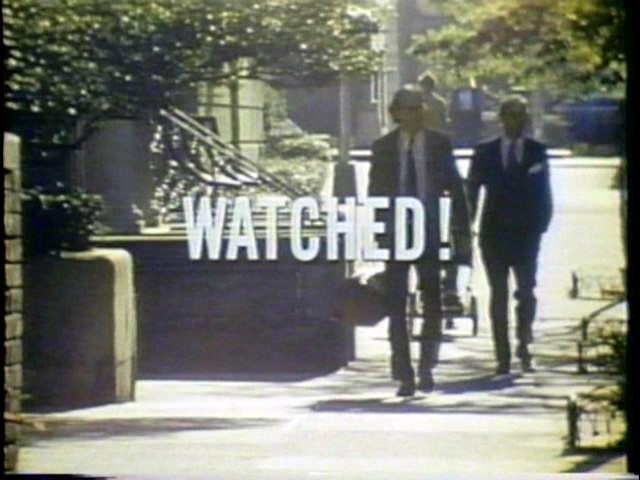

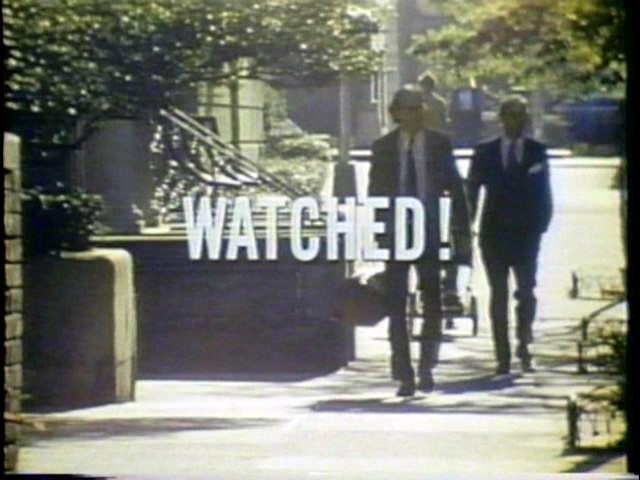

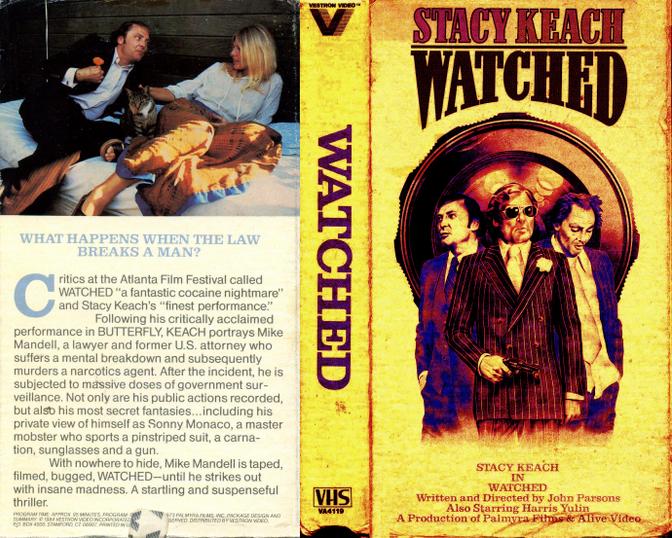

WATCHED! (1973/1974)

Had it not been for this movie, I would never have learned about

Michael H. Metzger.

It’s more than worth reading the profile of him penned by Nicholas Pileggi

and published in The New York Times on 16 May 1971, pp SM34+.

I never thought I would have any sympathy for any law-enforcement agent, but this case is a little bit different,

for a merciless sadistic psycho finally saw the light and mended his ways, only to be persecuted for it by his former colleagues.

He quit law enforcement and switched sides to become an attorney for the accused.

In defending one case, he obtained drug samples for testing at a lab superior to the one that the prosecution had used.

For that he was busted on a possession charge.

He knew the methodology of the prosecution well enough that he was able to extricate himself from that morass, and Pileggi commented:

What Metzger’s arrest

and pretrial hearing did was

to bring into public focus one

of the murkiest areas of law

enforcement today. His case

was unusual only in the fact

that the defendant had the

technical knowledge to put up

a defense and the money (it

cost him $25,000 in fees and

expenses) to afford it. The

overwhelming number of men

and women arrested every

year on narcotics charges,

however, are not so fortunate.

They are the real victims of

abusive police practices and

of what the legal profession

has come to call the

victimless crime.

Unfortunately,

as we read in “Drug Prosecution of Coast Lawyer Will Be Resumed,”

The New York Times, 2 January 1972, p. 45,

his “not-guilty” verdict was appealed.

(Weren’t we all taught in school that this can’t happen?)

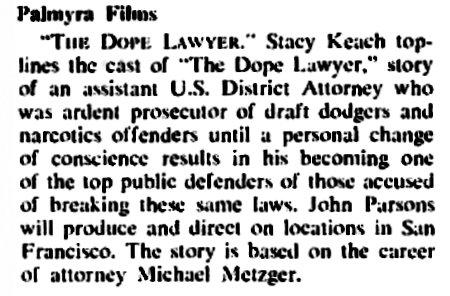

Pileggi’s story was compelling,

and it is not surprising that a movie would be forthcoming.

Barbara Bladen, in her column “The Marquee” in

The San Mateo Times, Monday, 7 August 1972, p 14,

published a profile of Stacy Keach, the 31-year-old rising star.

Among other things, she noted:

...He’ll be moving to San Francisco next month to write and

film the Michael Metzger story about a New York prosecuting

attorney who while handling narcotics and draft dodge cases,

became disillusioned by the corruption within the police department.

He moved to San Francisco and turned defender.

John Parsons, a New York documentary filmmaker, is

cowriting for the 90-minute project that has NET support....

That calls for further study.

John Parsons was an investigative reporter for WCBS-TV 2 in New York City,

but lost his job and found himself working in the same capacity

at the public-television outlet WNET-TV 13 in the same city.

In his new job he had made a documentary program on NY DA Frank Hogan,

which, judging from an article by John J O’Connor, “District Attorney Hogan Viewed by WNET,”

in The New York Times, 1 December 1971, p 95,

was none too complimentary.

Among those he interviewed on camera was Michael H. Metzger.

So Keach, Parsons, and even Metzger himself set out to make a dramatic TV movie for WNET,

but it didn’t turn out the way one would have expected.

It became a 16mm feature destined for 35mm cinema release with more than the usual amount of “artistic license,”

and at the end the Metzger character, called Mike Mandell and played by Keach,

turned out to be the looniest and most dangerous character in the whole story.

(Actually, considering the obituary in the link above,

where we learn that Metzger shot his wife with a bird rifle and then killed himself,

perhaps Keach and Parsons knew exactly what they were doing.

Bear in mind that it’s not well-adjusted, emotionally balanced, fair-minded,

serene people who choose to go into law enforcement.)

After that, the story of the movie gets murky.

The final shooting script (no, I have not seen it)

was a work, basically, of pure fiction,

and as such would certainly not have been approved by the documentary department of WNET.

So it is not surprising to read about a different producer taking on the project.

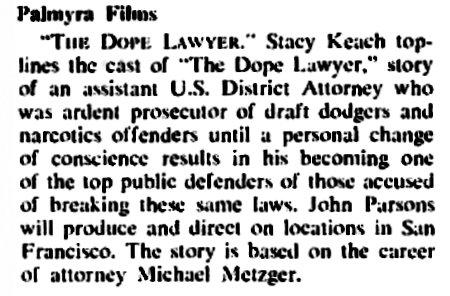

Take a look at this announcement from the 4 September 1972 issue of Boxoffice:

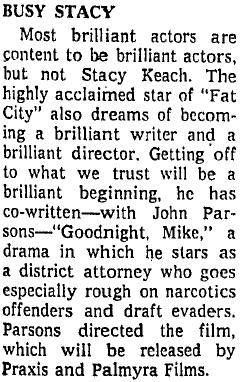

Then a second company, Praxis, was added, and the title was changed to Goodnight, Mike,

as we can see from A. H. Weiler’s column in The New York Times, 12 November 1972, p. D11:

The movie was completed in 1973 and bore a 1973 copyright,

but by the spring of 1974 it still had not been released.

Penthouse, as you can see from the above, was not mentioned in any way.

So my guess — only a guess —

is that the Penthouse managers saw an opportunity when they learned about this movie.

The entertainment value was rather low, but it was nonetheless an intriguing little movie,

with top-notch direction and startlingly naturalistic acting,

and it featured in the lead a magnificent performer.

Despite its promise, it had unaccountably been collecting dust on a shelf somewhere in Hollywood.

Take a look at this excerpt from an article by Robert F. Hawkins,

“Penthouse Mag Goes ‘Conglomerate’,” which appeared in the weekly

edition of Variety on 22 May 1974:

The above sentence seems, on the surface, to be about two stories:

(1) the Keach movie and (2) the Alice Cooper movie.

Actually, it is about a third story as well:

(3) the misleading statements made by Penthouse to Hawkins.

The implication of Hawkins’s sentence

is that the movies were in “active production” by Penthouse,

whereas in fact they had already been completed, and not by Penthouse.

After the Stacy Keach starrer had collected dust for over a year,

Penthouse licensed or purchased the distribution rights for what I presume was a rather small amount of money,

in full expectation of being able to rent it to exhibitors.

Unsatisfied with either of the proposed titles,

the Penthouse executives had probably three or four hundred board meetings

and ultimately settled on the simpler and more ominous Watched!,

emphasizing the surveillance aspect of the story.

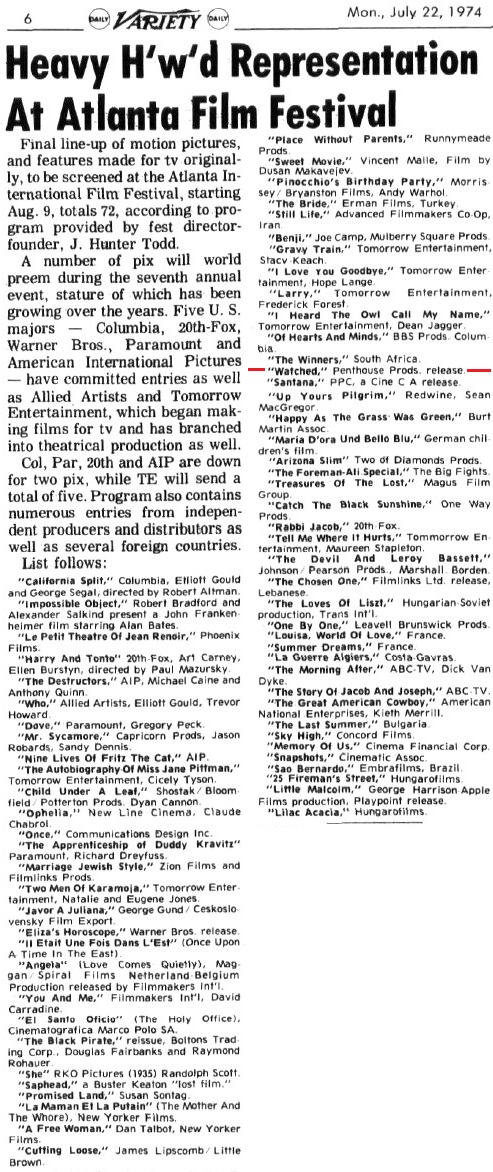

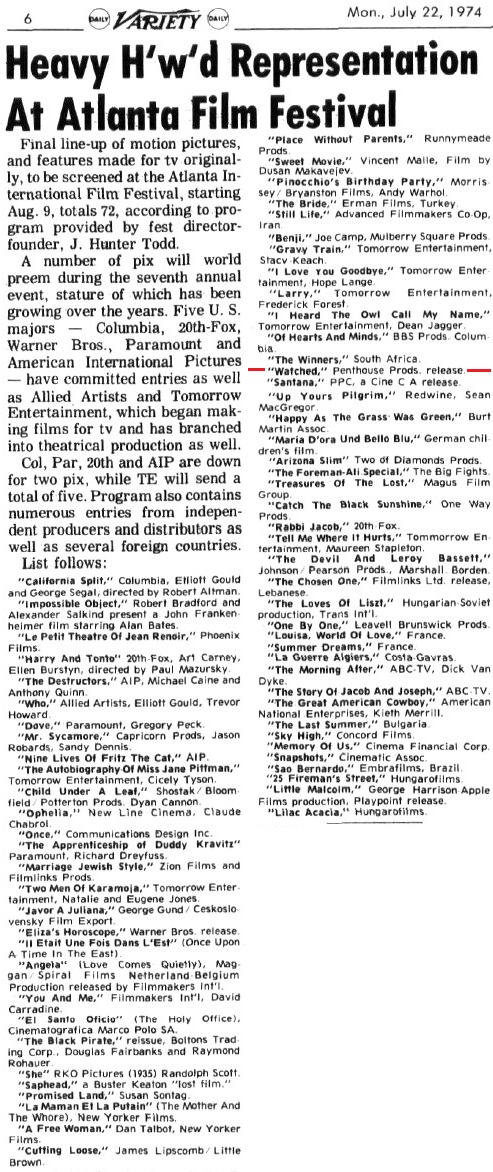

Watched! premièred at the Atlanta International Film Festival in August 1974.

I had been unaware of any Atlanta Film Festival held in 1974.

The current Atlanta Film Festival dates back only to 1976.

So what’s all this about an Atlanta Film Festival in 1974?

Well, there was one. The Seventh Annual Atlanta International Film Festival, 9–18 August 1974,

presented at the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center in three auditoriums:

the 1,750-seat Symphony Hall, the 750-seat Alliance Theatre, and the 450-seat Walter Hill Auditorium.

The founder and director of that Festival was

J Hunter Todd,

and the president was

Leroy B Sherman III.

Todd’s assistant was Holly Conover. Board members were

Jay Lovins (Threshold Films),

Elmer Bernstein,

Sheldon Leonard,

Louis de Rochemont,

David Wolper, and

Marvin Chomsky.

On the Buyers Committee were Jerry Rappaport (International Film Exchange),

Peter Schillaci (Contemporary Films/McGraw-Hill),

Leo Dratfield (Phoenix),

Myron Bresnick (Macmillan Audio),

Samuel Berns (Berns & Berns),

Robert Shaye (New Line Cinema), and

Christine Kieffer (Les Films Christine Kieffer).

On-site judges included Leon Uris,

LeRoy Neiman, and

Kathleen Carroll.

Daily Variety, Friday, 22 July 1974, p 6:

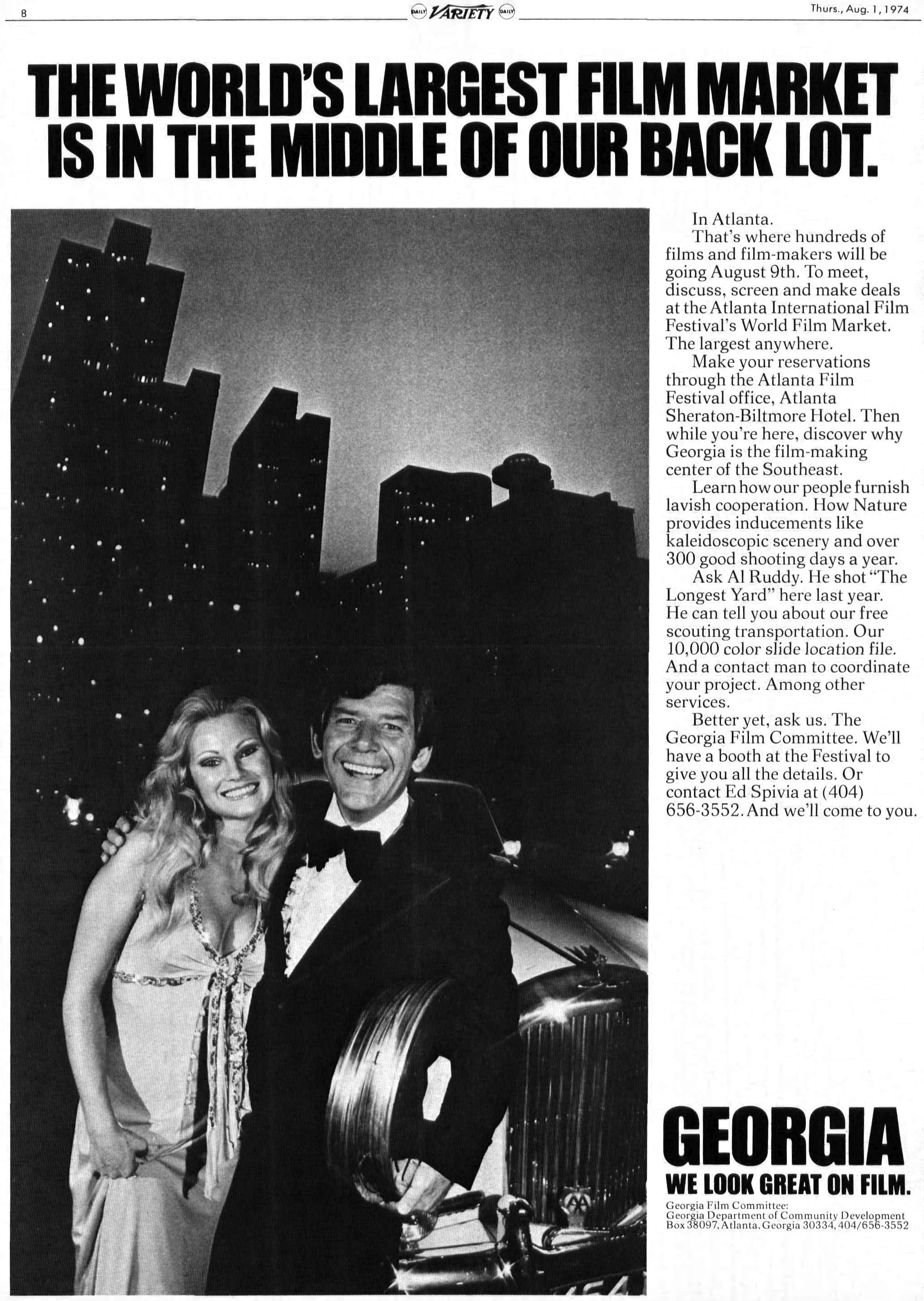

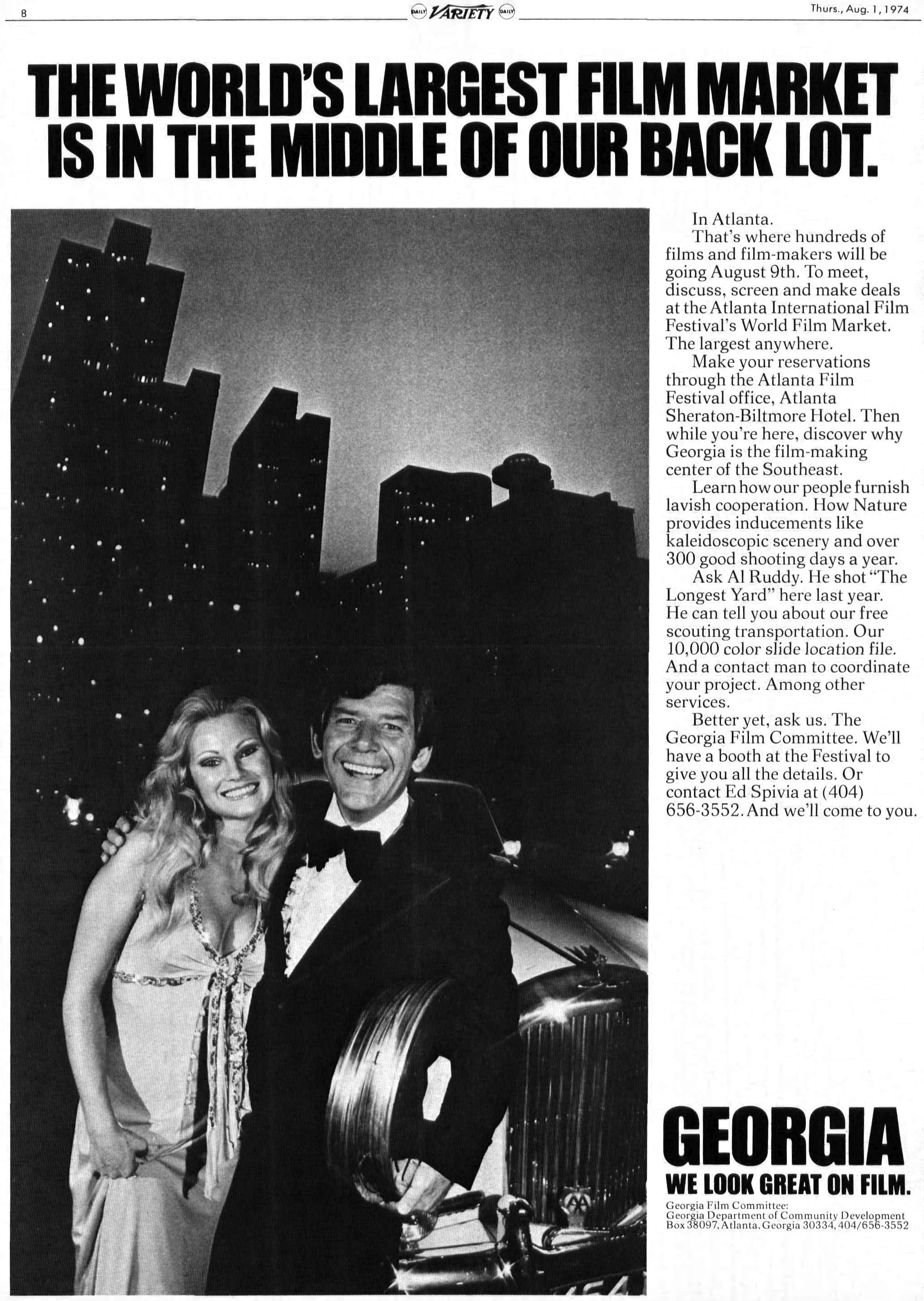

Daily Variety, Thursday, 1 August 1974, p 8:

Variety, Wednesday, 9 August 1974, p 6:

Daily Variety, Tuesday, 1 October 1974, p 5:

Watched! did not win any prizes. (Well, neither did the “Salute to Buster Keaton,” so hey.)

According to IMDb

Watched! was released in September 1974,

but I can’t find any evidence of a release anywhere.

Actually, it was presented at the Carnegie Hall Cinema in Manhattan on

Wednesday, 11 September 1974, apparently as part of a film festival or trade festival.

To quote from the review by “Robe” in

Daily Variety,

Tuesday, 17 September 1974

(and republished in the weekly edition the following day):

Penthouse Prods. release of a Palmyra Films production....

Part of a package of

films shown at the Atlanta Film

Festival and brought into New

York by the Carnegie Hall Cinema,

this theatrical debut for television

writer-director John Parsons is an

often erratic effort to make a

worthwile statement about surveillance

but falls short of Francis

Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation”

for the time being the definitive

work on the subject....

“Robe” continued with some criticisms I don’t really understand,

unless the gripe is about supposed surveillance footage looking too elaborate to have been shot with hidden cameras,

or maybe the imposibility of 8mm silent footage being shown on a 16mm projector with dialogue track.

I don’t know:

Technically, the film is a mixture

of misused professional talent and

unrestrained amateurism. The

camera work (four cameramen

are credited) is choppy and lacks

control. This is surprising considering

the fact that Parsons’ experience

has been in tv, where tight

control is the first thing learned.

There is apparently little interest

for the commercial market unless

the “surveillance” angle is exploited.

We can see from the next snippets that Watched! was also shown on the last day of the San Sebastian Film Festival,

14–25 September 1974.

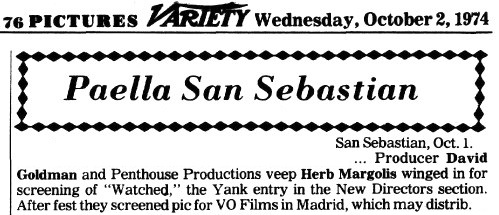

Variety, Wednesday, 18 September 1974, p 4:

Variety, Wednesday, 2 October 1974, p 76:

Want some more?

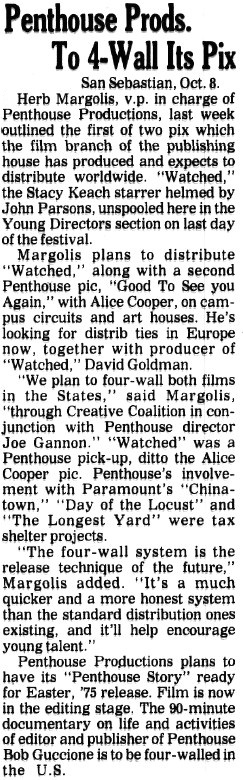

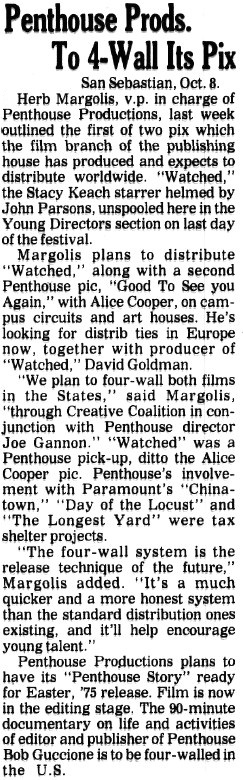

Variety, Wednesday, 9 October 1974, p 26:

Penthouse Story was never completed. I don’t know what happened to the rushes.

There was no mention of Penthouse anywhere in the on-screen credits,

and neither was there any mention of Praxis.

So “Praxis” was either a misprint or it had bailed out of the project.

Or maybe it was a silent partner. I don’t know.

This is the production credit that we see on screen:

We need to find out what exactly Alive Enterprises and Palmyra Films were.

Palmyra was either a DBA or it was a one-shot production company,

as it seems not to have done anything else.

If you know something about it, please contact me. Thanks!

Alive Enterprises, though, is a bit easier to trace.

It is an indie that handles, among other things, the Alice Cooper band.

That ties in perfectly with the article excerpted above.

Apparently, Penthouse was unable to interest any exhibitors in booking the film.

My guess — again, only a guess —

is that Penthouse Productions Ltd, as the brand-new kid on the block,

was simply not recognized as a valid distributor and was ignored.

The workings of the movie business are not significantly different from the workings of the mob.

Newbies are not welcome.

Further to confuse/elucidate the issue is the

IMDb,

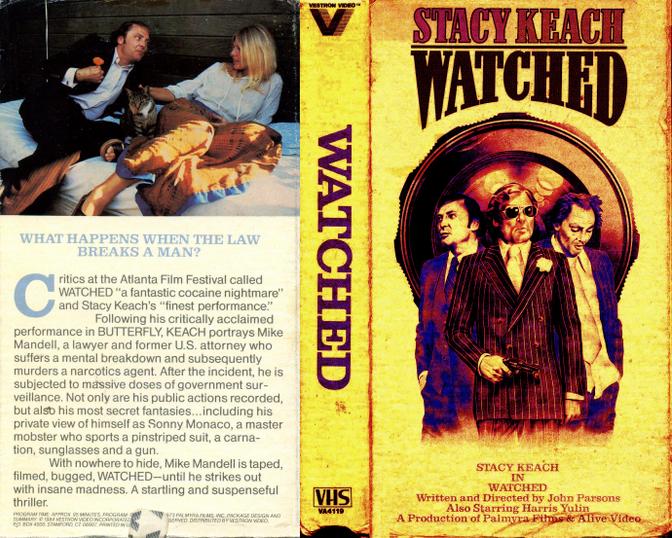

which claims that the VHS of Watched! was released by Penthouse Video in 1984.

It was not; it was released by Vestron Video in 1984.

So whoever compiled the info for IMDb apparently crossed some wires.

The Vestron VHS of Caligula

sported a ‘PENTHOUSE VIDEO’ attribution on the spine,

and for an IMDb informer to report that the Vestron VHS of Watched!

was also released by ‘Penthouse Video’ is pretty good evidence that the

informer got the two tapes at the same time and confused them.

Indeed, by the time of the video release, Penthouse had sold off all rights to Watched and had no further interest in it.

The VHS cover above supplies us with another maddening clue, quoting, without attribution,

one or two reviews from unnamed critics at the Seventh Annual Atlanta International Film Festival, 1974.

Where can we find those reviews?

There’s something else curious about the VHS cover as well.

Do you see what I’m talking about?

There is no rating.

Normally videos at the time carried a G or PG or R or X somewhere on the front and/or back cover — but not this one.

Yet the Variety review by “Robe” explicitly supplied the film’s rating: R.

This movie was offered to video shops, as far as I can tell, with no fanfare.

As a straight-to-video title, it garnered no reviews and died the quietest of deaths.

Why did the video shops take this unknown and hence unrentable movie?

Well, back in those days, a videocassette retailing for $59.95 or $69.95 or $79.95 or $89.95

would wholesale for two dollars, or maybe three or four dollars, or five at the most.

So in a bulk order of several hundred titles, what was the harm in risking an extra two dollars

if there was a small chance of a payoff if a Stacy Keach fan spotted it on the shelf and was happy to fork out the $89.95 or whatever on it?

I don’t know how video shops worked in later years, but that’s about how they worked back then.

The irony is that this movie is actually pretty good.

It was certainly better than most movies of the time, and better than anything being made in Hollywood now.

If some museums and archives and the occasional revival house were to promote this

as Stacy Keach’s great lost movie, it would probably be received quite well

and audiences would be surprised that this movie had slipped them by.

It would be nice if someone were at last to give this movie the public recognition that it deserves.

If you know more than I do, please let me know.

Thanks!

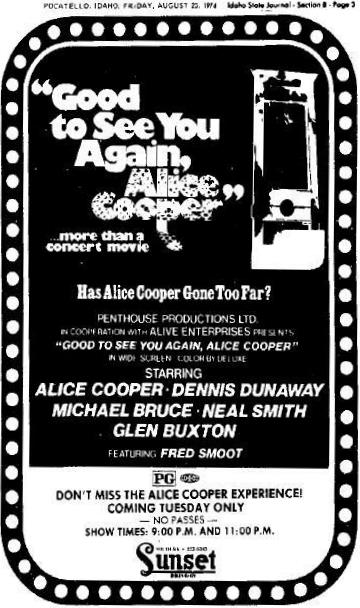

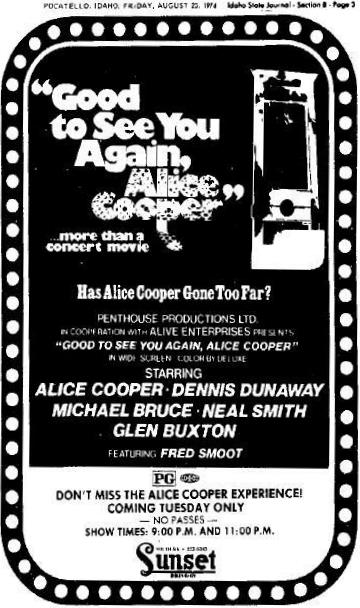

GOOD TO SEE YOU AGAIN, ALICE COOPER (1973/1974)

As for Hard Hearted Alice (compound modifier wrongly unhyphenated),

Penthouse had a little more luck — very little.

The movie was previewed in July 1974 under a new title,

Good to See You Again, Alice Cooper,

and then it was gradually released beginning in August 1974.

(When I got the DVD,

I was thrilled beyond words to see that my friend James Randi performs in it!

He plays the Dentist and the Executioner,

and he created the magic tricks of the beheading and whatnot.)

As far as I know,

this advertising campaign was the first public announcement of Penthouse Productions, Ltd.,

and it was unquestionably a last-minute decision to use that wording in the ads.

On the commentary track to the DVD,

lead singer Vincent Furnier says that Penthouse distributed the movie,

and he significantly makes no mention of Penthouse having been in any way involved with the actual production of the movie.

He’s surely right.

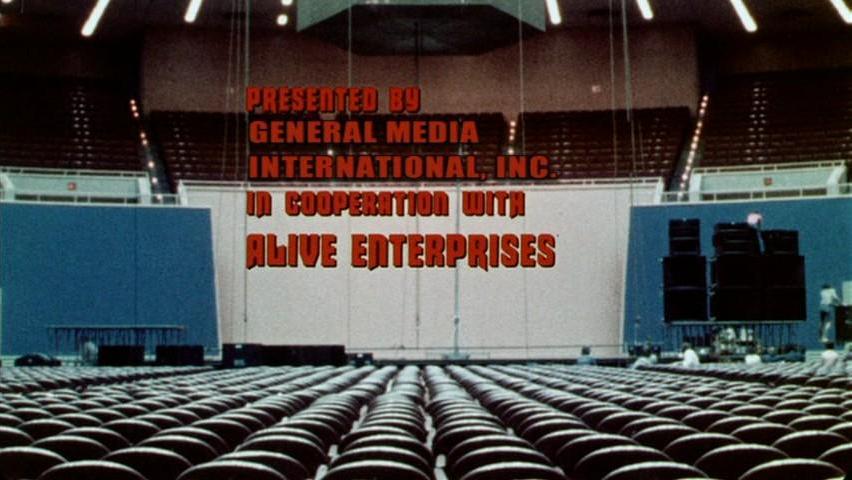

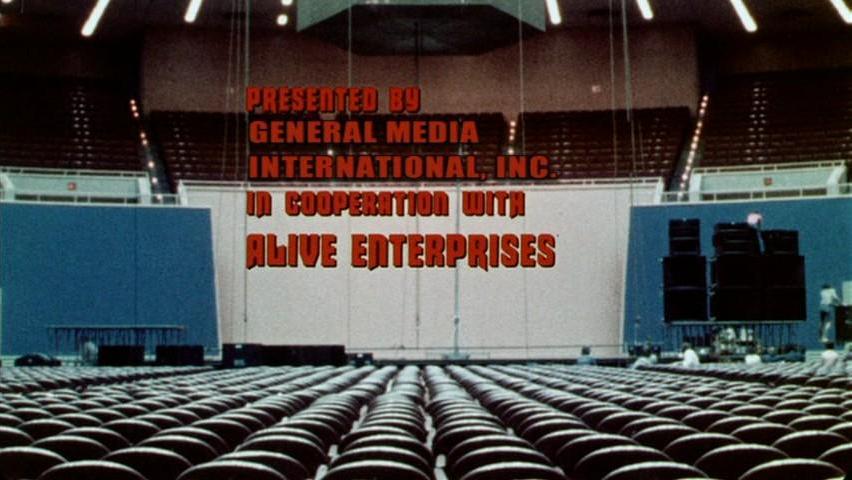

And when we look at the credits, this is what we see:

General Media International, Inc., was the name of Bob Guccione’s umbrella corporation,

and it was a name he seldom printed anywhere, preferring to list only his smaller Limited Companies.

So this credit is a bit surprising.

There was no mention anywhere in the opening or closing credits of the name Penthouse.

Now, a “PRESENTED BY” credit is not the same as a “PRODUCED BY” credit.

As the presenter, General Media Inc/Penthouse Productions Ltd

simply purchased or licensed the distribution rights to a

pre-existing movie, just as Furnier implied.

It is easy to see why Penthouse thought this movie would be a good bet to earn an easy income.

Anyone even vaguely aware of popular culture in 1973/1974 would have recognized that

the Alice Cooper band needed no promotion;

the band was so wildly popular that its name alone sold the product.

Since the title by itself was expected to attract sell-out crowds,

there was no need to spend the usual six million on saturation advertising.

Instead, Penthouse would start it off in small towns and small cities on single screens

and let it build up a reputation, after which it would be picked up by major cinema chains.

So it seemed like a good deal, a natural, a plan that couldn’t go wrong.

And yet this movie sank with barely a trace and never played in the major markets.

After poor audience reactions, the comedy routines

(which are unfunny unless you’re in an exceptionally giddy mood)

were deleted and clips from old Hollywood movies were substituted in their place.

I guess that happened after the July 1974 previews, though I can’t be sure.

The recent DVD release is of the original version.

Why did the movie fail? I really don’t know.

Maybe fans were happy only with something new,

and had already had their fill of the “Billion Dollar Babies” tour,

the songs of which were readily available on LP?

Or maybe the movie was so poorly promoted that it simply passed under the radar?

Maybe. Heaven knows.

A little over a year later Penthouse got fed up and sold the movie:

Boxoffice, 3 November 1975:

Crescendo Will Distribute

‘Alice Cooper’ and ‘Julia’

FORT WORTH — Crescendo Cinema III,

Inc. and Cinema III Marketing recently

acquired four new pictures for distribution:

“Good to See You Again, Alice Cooper,”

“Lucky Johnny,” “Julia” and “When the

Line Goes Through.”

Perry Tong of Crescendo and Herb Margolis

of Penthouse Productions in Los Ángeles

concluded agreements on the rock cabaret

“Good to See You Again, Alice Cooper,”

starring Alice Cooper. The film includes

several film clips of such all-time

favorites as W.C. Fields, Betty Boop, Our

Gang and even clips from the Watergate

hearings “starring” Sen. Sam Irvin....

Cinema III’s John Parker said all calls

should be directed to the company’s new

metro line, (817) 29-3762. On the west

coast call Jock Gaynor, Wargay Corp., Los

Angeles, at (213) 276-3945.

It also was announced that Ben Taylor

has joined Cinema III as assistant to Parker

and Crescendo now has its own art department

for advertising. Hilton Snowdon and

Gary Myrick are full time staff members

of that department. |

Boxoffice, 27 October 1975:

Crescendo Cinema III, The Forth Worth-based

film company, has branched out into

distributing as well as producing movies.

Producer-director Perry Tong is dampening

his feet with “Good to See You Again,

Alice Cooper.” The film is being distributed

in the Forth Worth and Oklahoma City areas. |

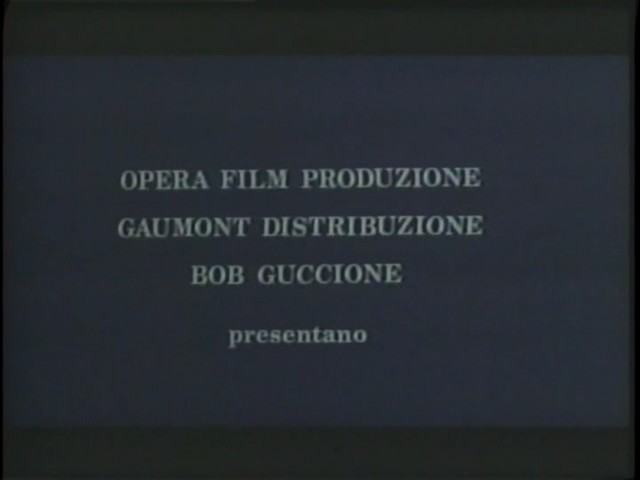

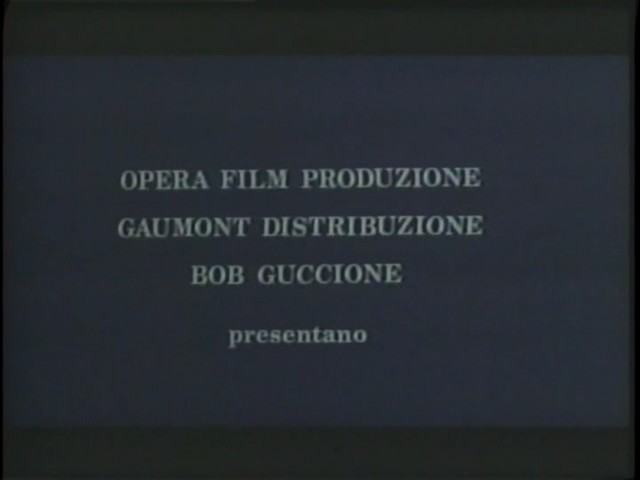

LA CITTÀ DELLE DONNE (1979)

maybe doesn’t really count.

The opening credits list this as a Franco Rossellini Production for Felix Cinematografica.

Guccione had contracted to fund this movie, though under the Viva imprimatur, not under the Penthouse name.

He seems to have raised money for at least some of the preproduction,

but then withdrew just as the cameras were ready to roll.

Franco Rossellini’s cousin, Renzo, came to the rescue and had his company Opera Film

coproduce it and his company Gaumont Italia release it.

Nonetheless, Guccione got a credit in the original release prints, which was almost immediately thereafter deleted.

Franco’s credit remains, even though he had nothing to do with the production proper.

I think I know why his name remained, though I can’t be sure because the paperwork all seems to be missing.

If you can fill me in, I’m all ears.

As you check around the reference sources, you will notice a number of other movies and TV programs

that were presented by Penthouse Productions or Penthouse Presentations or Penthouse One Presentations,

but they had nothing to do with Guccione.

That was a different Penthouse, which predated Guccione’s use of the Penthouse trademark, and it has caused much confusion.

The non-Guccione Penthouse productions that I know about are

The Secret Night Caller (1975),

The Shari Show (1975/1976),

Secrets of Three Hungry Wives (1978),

The Great Cash Giveaway Getaway (aka The Magnificent Hustle) (1978–1980),

The Secret War of Jackie’s Girls (1980), and

Dial 911 (aka The Two Lives of Carol Letner, 1981).

I spent several days of my life trying to track down information on these productions,

and so I hate to delete my research, especially since someone might find it useful.

So if you want to know about this other Penthouse, click here.

After these attempts to break into the market,

the Penthouse managers temporarily halted activities

and they retired Penthouse Films International Ltd altogether.

A few years later the sands shifted.

The executives decided to start up again with a recycled name, Penthouse Productions, and they further established Penthouse Home Video,

and together those two entities unleashed a number of videos for the home market.

The titles published at

IMDb — Penthouse,

IMDb — Penthouse Productions [us],

IMDb — Penthouse Home Video,

IMDb — Penthouse Video, and

IMDb — Bob Guccione

don’t look too promising:

Penthouse Love Stories (1986),

Penthouse: Fast Cars Fantasy Women (1991),

Desire (1991),

Penthouse: Ready to Ride (1992),

Virtual Photo Shoot: Volume One (1993),

Tonya and Jeff’s Wedding Night

(September 1994 — you know, the ones who tried to break Nancy Kerrigan’s

knee on 6 January 1994 so that Tonya would win the championship;

well, they then sold this tape to Penthouse),

Secret Lives (1994),

Penthouse: 25th Anniversary Swimsuit Video (1994),

Penthouse: 25th Anniversary Pet of the Year Spectacular (1994),

Kama Sutra: The Art of Making Love (1994),

Kama Sutra II: The Art of Making Love (1995),

Penthouse: Pet Rocks (1995),

Penthouse: The Wild Weekend with the Pets (1996),

Penthouse: The Art of Massage (1996),

Penthouse: Showgirls of Penthouse (1996),

Penthouse Pet of the Year Play-Off 1996,

Miami Hot Talk (1996),

Sex Off the Runway (1996),

Lipstick Girls (1997),

Penthouse: Confessions (1997),

Venus Descending (1997),

Love Games (1998),

ESP: Extra Sexual Perception (1998),

Penthouse Girls of the Zodiac (1999),

Penthouse Pet of the Year Play-Off 2001 (2000),

Call Girl (2000),

Fashion (2000),

Penthouse: Harlots of Hell (2000),

Dangerous Things (2000),

Dangerous Things 2 (2000),

Sex Opera (2000),

Amy and Julie (2000), and

Penthouse: Pets in Paradise (2001).

I have not seen, and shall not see, any of these videos.

The titles tell me more than I need to know.

Nonetheless I am curious about the business side.

What studios were used?

What were the costs?

Who provided the funding?

What was the advertising/release strategy?

How well did these videos do?

So if you worked on any of these videos,

I would be more than happy to hear from you!

After Penthouse’s bankruptcy, purchase, and reorganization in 2003–2004,

the new regime decided to continue and accelerate the Penthouse Productions activities.

You can see the result in the lists published at

IMDb — Penthouse

and at

IMDb — Penthouse Home Video [us].

I have not seen any of these later movies, and, judging from their freakish titles, I would not like to.

So now you know a very small part of Penthouse’s secret history,

the history that the old regime at Penthouse never wanted you to know about.

Now that I’ve told you about those secrets,

why don’t some of you tell me about the hotel/convention-center/residential project planned

for Atlanta, Georgia; or the Penthouse Atlantic Hotel and Penthouse Casino planned for Atlantic City, New Jersey?

Who wants to tell me about all the magazines:

Lords, Leisure, Longevity, Photo World, Forum, Viva, Omni, Variations, and any others?

One magazine that the Penthouse group published, or perhaps co-published, was

Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Defense and Technology International.

According to Diane Reese’s article, “Penthouse: When Sex Doesn’t Sell,” in the January 1987 edition of

Folio: The Magazine for Magazine Management,

“The controlled-circulation publication, the company’s first,

is aimed at government and military personnel involved in the planning of defense systems, both in the United States and abroad.

A portion of its content is devoted to scholarly papers.

It is the only magazine dealing specifically with these three defense technologies, according to Guccione.

The Penthouse creator didn’t create this one, however.

The idea was brought to him by Evan Koslow, a Ph.D. and defense consultant

who is the magazine’s associate publisher and executive editor.

But Guccione’s agreement to found it shows clearly that Penthouse still goes where his curiosities lie.”

I had done WorldCat searches in the past and come up empty-handed.

But I just tried it again now and discovered a few library holdings.

Publication began sometime in 1986 and the publisher is listed as NBC Defense International Ltd of New York City.

Oh how I would love to get the entire run for my collection!

Who wants to tell me about Minotaur Press and Odyssey Press?

Who wants to tell me about Newsconcorp?

Who wants to tell me about the proposal for off-shore powerboat racing in the UK?

Who wants to tell me about the proposal to re-open Manhattan’s Copacabana Club?

Who wants to tell me about the proposed London weekly and about the proposed Bravo?

And what ever happened to PET Penthouse Entertainment Television Network that was scheduled for transmission via SelecTV?

(See “Penthouse and SelecTV Team to Launch Adult Pay-See Tier,” Daily Variety, Tuesday, 16 November 1982.)

You can tell me. I won’t bite. Click here to reach me. Thanks!

|