THE SAGA OF |

|

But first...

|

|

For years I did not update this website, but just left it fallow.

After the devastating events of 2017 through 2024, I now wish to make one final change, one closing comment:

NO edition of the movie — NO EDITION — is in any way authentic.

EVERY EDITION of the film is a violation of the director’s ideas.

EVERY EDITION of the film has been twisted, altered, butchered, tortured.

Helen and Malcolm say otherwise, but they don’t have a clue what they are talking about.

They acted their scenes the way the director wanted, but, beyond that,

they had no idea, not the foggiest notion, what the director was after for the overall film.

Do NOT write to me to inform me of the “wonderful news” that

some unidentified “they” have found the missing footage.

|

|

How Caligula Cursed the Cast and Crew, How It Cursed My Life, and How It Cursed the Lives of My Friends (keep scrolling down) It’ll Never Happen. Sorry. It Just Won’t. You’ve Been Wondering for Four Decades: The Mythical 210-Minute Version The Multiple Versions Opinions about the Movie Audience Reactions Press Cuttings The Mysterious Death of Anneka di Lorenzo Tie-Ins, Promotional Items, and Other Such Phenomena The Other Franco Rossellini Movies The Other Penthouse Movies The Writer Who Disowned the Movie You’ve Been Wondering for Six Decades: Gore Vidal’s The Director Who Disowned the Movie Stuart Urban Remembers Working on Caligula The Posters and Print Advertisements You Know More Than We Do Alan King’s TV Special on Caligula The Cast and Crew The “Pets” Every Screening and Booking We Have Learned About Bob Guccione’s Flirtation with Thermonuclear Fusion Incredibly Difficult Translations That Gave Us Mountains of Migraines Oodles and Oodles of Caligulas The Real The Real Reason Why You Could Never Learn Greek and Latin (Hint: No, They’re Not Hard, and No, You’re Not Stupid) Interesting External Links Contact |

|

|

Championed by a few, loathed by the many,

Caligula is surely among the most mangled, mutilated, misunderstood movies in cinema history.

There are several

|

|

More than that, though, this movie is not a movie.

It is an act of defamation.

What reached the screen was a distortion of the film that its makers had made.

In conception, Caligula was an absurdist comedy, though with a few horrifyingly disturbing scenes.

It was meant as a joke, and political power was the butt of that joke.

The editing crew (among the best in the world),

the

|

|

The production audio offered next to no guidance either.

What was the movie supposed to have sounded like? We may never know.

Those familiar with director Tinto Brass’s previous films

would recognize that a standard Hollywood mix was not among his arsenal of tricks.

His sound design was always off the wall.

Where others would introduce reverb, Tinto avoided it.

Where others would make dialogue crystal clear, Tinto obscured it underneath effects.

Where others included every background noise, Tinto either elminated it or used unrelated background noise.

Where others would use comical music to heighten the humorous aspect of a scene, Tinto went fully dramatic — and vice versa.

Where others would use a rich mix of sounds, Tinto would use a dry track — and vice versa.

He never once broke the rules for the sake of breaking the rules.

He broke the rules because he had better ideas, ideas that would fit the characters and situations better.

|

|

The

|

|

Not knowing what else to do, the crews invented a soundtrack of cavernous echoes and distant sounds of wailing,

and avoided any hint of silence, no matter how brief.

That design contradicted the scenes of comedy, of slapstick, of ridiculous and preposterous images,

and whenever there was a contradiction, the images were deleted in consequence.

When the sounds contradicted the jokiness of the dialogue, that dialogue was either changed or deleted altogether.

|

|

The result?

It was an offense.

The absurdist comedy was efficiently transformed into a dark brooding of bloodlust, beheadings, tortures, corpses,

that seemed to take a macabre delight in every form of cruelty.

Colors were darkened in the lab to darken the mood further.

What had gone wrong?

Here I risk causing offense to those whom I have befriended over the years in my research into Caligula.

|

|

This is what had gone wrong:

Bob Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine,

had attached himself to this production for the sole purpose of intercutting Shakespearean actors with hardcore sex scenes.

Nobody on the film crew knew or suspected that until too late.

Why was this his interest?

Answer: He wanted to change the law, he wanted to put an end to vice squads raiding porno houses,

he wanted to ensure that hardcore would be permitted at mainstream cinemas,

and he wanted to guarantee that hardcore films would never again be restricted to off-the-beaten path porno cinemas.

That begs the question: Why?

He and his group of Penthouse companies had no legal standing in overturning such laws and restrictions.

Guccione and Penthouse were not operating porno houses nor were they distributing porno movies.

Despite having no involvement in the business, Guccione went out of his way

to make the world safe for distributors and exhibitors of hardcore sex movies.

He went out of his way to obtain legal standing in this matter.

He essentially wanted to close down the porno houses and move hardcore movies into mainstream cinemas.

So: Why?

When I use my imagination, I think I can

guess the correct answer.

I think you can, too.

|

|

The Caligula crew had dared not shoot any hardcore scenes,

which were strictly illegal and which would have resulted in severe penalties,

up to and including lengthy jail sentences, hefty fines, confiscation of the film,

and government seizure of the production offices and facilities.

(Italian law in 1976 exempted fellatio and ejaculation, as far as I know, but nothing else.)

Tinto had a morality clause in his contract,

forbidding him from doing anything illegal or disreputable, on the clock or off.

I suppose that many or all of the others on the crew had a similar clause.

So, how did Bob manage to get his hardcore filmed?

Simple: He filmed those sequences himself, weeks after production had finished, late at night, when nobody was looking.

Through a legal loophole, he was able to spirit the hardcore footage out of the country

before the authorities could catch on to what he had done.

Audiences who saw the result were alternately assaulted by blood and guts on the one hand,

and

|

|

That is why I say that Caligula is defamation of character.

It is not a movie.

|

|

My goal back in early 1979 was to learn enough about this movie to write a pamphlet about it,

maybe 100 pages, certainly no more than 150 pages.

I wanted simply to describe Gore Vidal’s screenplay

and follow that with a brief description of the film as Tinto Brass had directed it.

That’s all.

I just wanted to know why Gore and Tinto had both disowned the final product.

Simple as that.

Alas, there was no information anywhere —

no script was available, and no shooting records could be found.

Then in the autumn of 2003 there was an announcement that the Gore Vidal Papers were to be housed at Houghton Library at Harvard University.

An inquiry confirmed that many Caligula-related papers were included in the collection.

They were treasures, and I spent a total of four weeks there —

four weeks that opened me to many new ways of thinking about many things, not merely Caligula.

Then in early 2007 I got a brief glimpse of some of the contents of the film vault.

That changed the story almost entirely.

At the same time I began to acquire the previously unknown storage locker rented by Caligula producer Franco Rossellini.

(Yes, Franco Rossellini was the producer of Caligula. You didn’t know that, did you?)

Over the course of almost two years, three friends helped me acquire the bulk of the contents of that storage locker.

We tried to get every scrap, but that proved impossible.

We got the most important items, though.

Frustratingly, there were many gaps in those four crates of papers.

Why was I surprised in July 2012 to discover that about 800 of Franco’s missing pages were held at Duke University?

I paid a freelance researcher to photograph all the relevant materials there.

In 2014 I discovered that a goodly number of items from Bob Guccione’s personal Caligula collection were being auctioned.

Again, with the help of friends around the globe (“The Gore Vidal’s Caligula United Front,” we called ourselves),

I managed to acquire a fair number of those items.

Then papers stored in the attic of a house, papers that had been destined for the rubbish heap, were shipped to me instead:

two crates of documents from Twickenham Studios relating to the protracted editing of Caligula.

Just as the book was two short leaps from the finish line,

I got full access to pretty much everything else, which, again, was just days away from being dumped into a landfill.

Hundreds of hours of film, probably every frame that Tinto shot,

|

|

More precisely, I was searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

From the day I was allowed into the archive, I feared that the tide would turn and that I would be locked out again.

After about eight months of having the doors swing open wide whenever I had a few hours to spare, there was the inevitable lawyerly roadblock:

Continued admittance would hinge upon my signing a series of

|

|

It was not the closing of the doors that turned me into an emotional wreck.

There have been adventures of late.

They were not always good adventures.

Some were pretty darned devastating adventures, draining adventures, and most were tied to this book.

So many novel (mostly bad) things happened from October 2016 through July 2017 that those nine+ months seem as long as fifteen years.

28 June 2017 through 10 July 2017 seems like two and a half years.

So I decided:

This book has caused me too many problems, has taken up too many years, has started too many arguments,

has ended friendships, has prevented me from pursuing other activities,

has gotten me stuck in offices with too many vampires, and has resulted in too many emotions.

On top of that, it has cost me all my savings and then some.

Nearly the entire book consists of details about conflicts — major conflicts.

I dislike conflicts. I dislike even learning about them. They drain me.

Nonetheless, these particular conflicts were important, and most of them were unknown, and remain unknown.

The conflicts spilled over from the page and into real life, and so I found conflicts all around me.

After ten or so years of people verbally beating up on me,

some instantly treating me as Public Enemy Number One, I entirely lost interest in the book.

I was tired. I was tired beyond description.

Burnout. That’s the word I was looking for. Burnout. Despair, too.

That’s another word that described my feelings.

Add to that despondency.

Add to the despondency the horrifying results of the 2016 elections.

I knew that all options were dreadful and dangerous, and I was apprehensive about any outcome, but we got the worst.

Many of you will disagree with me completely. Fine. Maybe the new laws are helping you.

They are not helping me, nor are they helping the people I care about.

Why was I wasting my time on a book about a dumb movie when I could be working to help make things better?

I also realized that, though the book was never in any way designed to give Penthouse publicity,

its publication would inevitably have that result, and I had no wish to give Penthouse publicity.

This was a worthless endeavor, I decided, and so I cut my losses.

Upon making this decision, I felt better.

Upon surrendering the key to the new archive, I slept better than I had in many months — not well, but better.

Maybe, just maybe, I’ll do some useful things for a change. Hoorah.

|

|

During the year or so after I was kicked out of Penthouse, there were changes.

The lawyer either resigned or was kicked out.

The other exec was also kicked out.

Penthouse filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy,

and soon after it was in the hands of the receivers,

who sold it to a new outfit called Dream Media (run by High Times),

which sold it at auction to porn behemoth WGCZ of Prague for $11,200,000.

WGCZ quickly made the corporate decision never to allow Tinto anywhere near any of the materials,

and to go out of their way to treat him as though he were a bucket of excrement.

I worry that the archives are now doomed.

From what I understand the

|

|

In case you’re wondering, I confess: I am not a fan of Caligula.

I think the world of Gore Vidal.

I think the world of Tinto Brass.

In numerous interviews, Malcolm McDowell expressed his conviction that,

buried beneath the mess, there is a great movie struggling to get out,

if only it were to be edited properly.

Until recently, I agreed.

Then I saw some more rushes, and I saw what survives of Tinto’s first draft of the rough cut.

I thought it was dreadful.

Once I saw that, well, I was deflated.

I had been eagerly pursuing a whole big bag of nothing for all those years.

I felt so stupid.

More recently, I understood that Malcolm had no idea what in the bloody heck he was talking about.

|

|

Yet I need to rethink my opinion.

I have watched Alex’s documentary on the movie countless times,

and I now see things in a new light.

The sequences in the first third of the movie that ruin everything else

are the sequences that deal with the harem collected by Tiberius for his lair.

Yes, this idea came from a tale told by Suetonius, but the movie turns it into nonsense.

There was no conviction to these scenes, nothing to which one can relate, no realism, no drama, no comedy.

It was absurdism gone bad.

The result was almost as bad as The Deer Hunter,

and the entire rest of the film was sabotaged by these earlier sequences.

Yet now, I wonder:

Was it good after all?

The release version of the film follows Tinto’s rough cut quite closely in these sections of the film.

Thought experiment: What if the sound were as absurd, as

|

|

Up through 1972, Tinto’s movies had been so extraordinarily good, the works of a genuine artist, a brave artist,

filled with

|

|

So, yes, I admit, there are wonderful things in the movie.

There are some stunningly beautiful images.

The absurdist comedy sometimes works.

The thick, unreal, dreamlike atmosphere sometimes works.

Mnester’s Pyramid of Power makes the whole rest of the movie worth enduring.

Yet there is something terribly wrong.

|

|

There were two problems with Caligula.

First, there were too many cooks.

Second, nobody — not Gore, not Tinto, not Danilo, not Franco, and certainly not Bob — had a clue about the true story.

They were all blinded by Suetonius, whose scurrilous work is still so powerful two millennia later.

None of those five men had any clue that there were other sources, even contemporaneous ones, that were much more accurate.

The real story actually has some potential for insightful drama —

a dunderheaded egomaniacal sadist raised by sociopaths,

elevated to top position in a government that we would now classify as

|

|

Curiously, despite the ludicrous onscreen results, there is something addictive about Caligula.

Even some of the worst scenes have a marvelous moodiness, sometimes bordering on dreamlike.

What fascinated me, personally, was the puzzle.

The writer and director were initially cordial and worked together splendidly.

The friendliness evaporated in a single moment, and the two sued each other.

When they were through, both disowned the result.

Beginning on 4 October 1980, and for the next three and a half decades, I watched the movie probably well over fifty times,

analyzing every last detail under the microscope,

trying to discern what had been cut out, rearranged, rewritten in the dubbing;

I was endlessly trying to imagine what the movie was supposed to have been like.

That is why I was addicted.

|

|

Addicted no longer, though. I shall never watch it again.

|

|

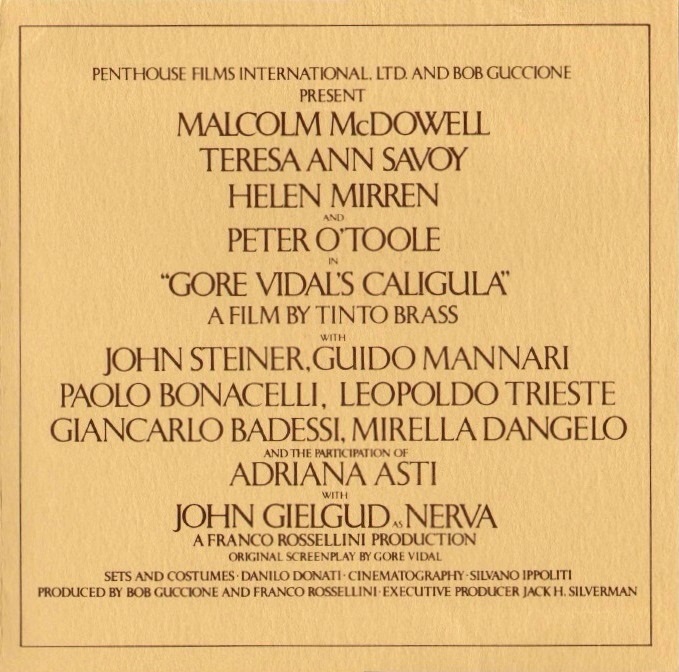

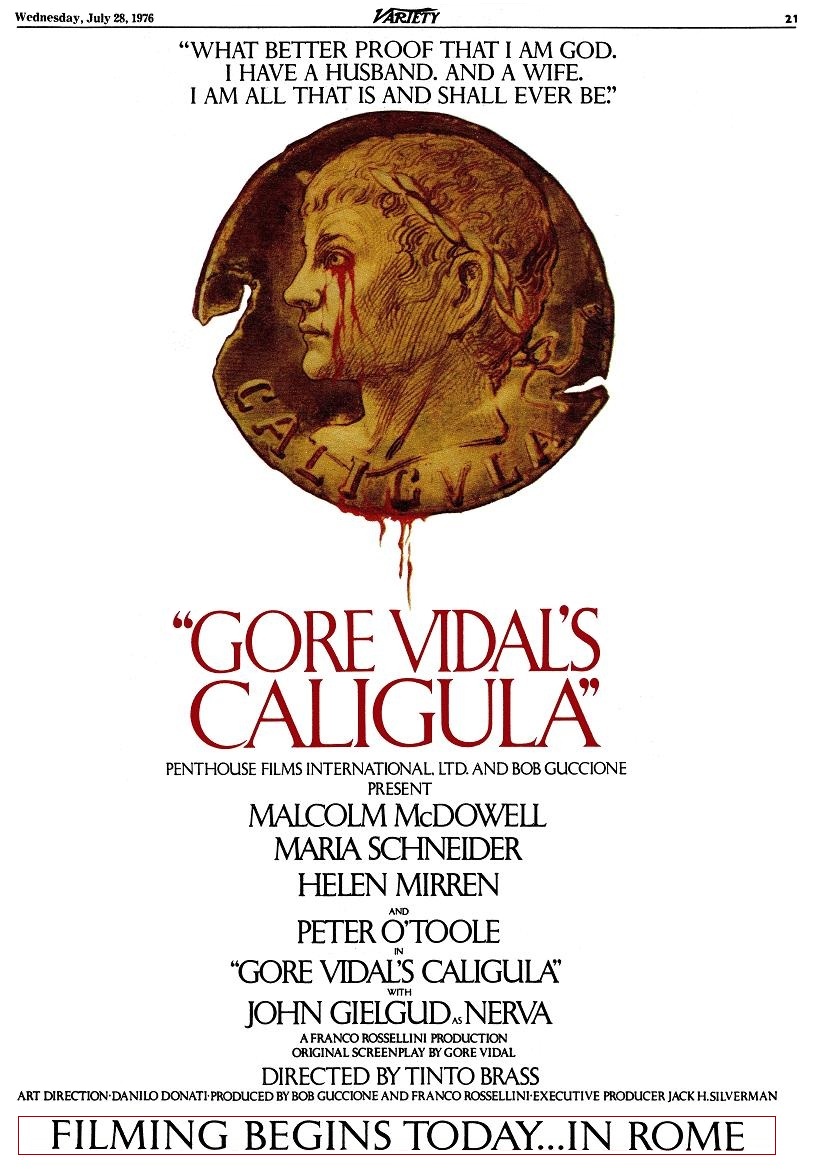

Now, let us look at the attractive advertisement

that announced the beginning of the filming.

As with nearly every contemporary press item about Caligula,

it was a lie:

|

|

|

Originally I had some pages on this site devoted to analyzing the film.

They were beyond erroneous. I junked them.

So stroll around through the links below.

Have fun.

|

|

As far as I am now concerned, the movie is not the story.

The story is the decade and a half of behind-the-scenes intrigues and legal battles.

Those are much more worthy of study.

You have never heard about most of those behind-the-scenes dramas. They were never published.

Not even the people who lived through the legal actions understood what they were doing or what was being done to them or why.

No judge could make head nor tail of the arguments and exhibits.

In its totality, the Caligula saga is a horrifying example of how the law works, both in the US and in Europe.

The story is truly demoralizing. It will weaken your hope for humanity.

No. That’s too optimistic. It will probably end your hope for humanity.

Writing that story took me from the beginning of January 2009 to the end of December 2014,

and I was discovering the story as I was piecing it together.

I didn’t study the evidence first and then summarize it later.

I wrote it as I was discovering it, which is why I had to go back and revise and correct probably every last paragraph multiple times

as I encountered each new piece of evidence.

The evidence told me the narrative, and I simply obeyed it. I did not impose my narrative upon the evidence.

Composing these chapters was a painful process, because the story is so awful, and because the good guys lost.

When I

|

|

As I wrote (or cowrote) the earlier chapters (1 through 27), I was laboring under the preposterous delusion that the story was

about the script, about the direction, about the design, about the actors’ neuroses, about the imposition of foreign concepts onto Gore Vidal’s vision,

about the entirely insane editing processes by people who had had nothing to do with the filming

and who were thus entirely unable to understand the footage dumped into their laps.

You thought that was the story, too, didn’t you? That was not the story.

The heart of the book became the story of the Rossellini-versus-Guccione conflicts, a gruesome and harrowing tale.

When I finished the

|

|

A great highlight of my life was when one of Franco Rossellini’s relatives read chapters 28 through 41

and approved them fully, without amendment.

Catharsis! I must have done something right!

She said I should iust go ahead and publish them as is.

So, okay, here goes, all of Part Five and the opening of Part Six:

|

|

Chapter 28, Money

Chapter 29, Partners Chapter 30, “Under No Circumstances Honest People Should Surrender to the Intidimidations of Irresponsable Criminals” Chapter 31, “Readjust Reciprocal Relations without Any Reservation or Restriction” Chapter 32, “Every Kind of Harassment and Abuse” Chapter 33, “A Shameful Attempt to Mislead the Court” Chapter 34, “Should I Abandon the Case?” Chapter 35, “Your Liver Is Not Functioning” Chapter 36, “I Did Not Give Directives to My Colleague” Chapter 37, “I’m Incorruptible” Chapter 38, “Empower the Good Relations” Chapter 39, “Such a Confused Situation” Chapter 40, “Penthouse Is Hoping That I Die and That My Company Goes Bankrupt” Chapter 41, “Good Sushi” |

|

If you can read these without suffering overpowering pains of empathy, you’re made of stronger stuff than I.

Well, either that or you’re a psychopath.

|

|

The other chapters, though, the ones dealing with the actual preparations and filming and editing and release,

they’re a whole different kettle of fish.

To publish them I would need to rewrite them from scratch.

Yes, I could do it.

No, I really don’t want to.

Rewriting those 800 pages or so would take only a few months, and the end result would be considerably less than 800 pages.

In my mind I can see it.

The problem is my energy level, which is nonexistent.

The bigger problem is my utter contempt for Penthouse.

To publish the book would require that my publisher’s lawyers draw out contracts with Penthouse’s lawyers,

and there is no point in even trying, as I entirely distrust Penthouse’s good faith in regard to any contract.

The result would be spending the rest of my life in court, getting drained of every penny.

Even if that were not the case, though, that company is so loathsome that I want nothing to do with it.

|

|

#30#

|